Welcome to America; now, please leave. About half of “Wrap Thee in Terror” is dedicated to the arrival of Alexandra Dutton, née of Sussex, on the shores of a new homeland. I have no idea how her precious ringlets survived a swampy month below deck, but I felt proud of Alex as the ship pulled into port. Emigrating is the first thing she’s ever accomplished on her own, without Spencer or her aristocratic privilege to help her (at least, not that much). When the lookout calls “Land, ho,” she’s first to grab her valise, eager to glimpse New York City and its streets paved with gold. (But also, obviously, lined with thieves and perverts.)

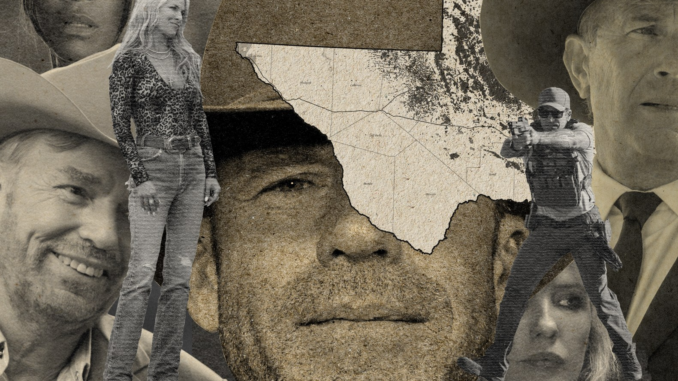

Except Alex is not disembarking in New York City because that would be actual progress. Instead, she’s rerouted to Ellis Island because it didn’t happen to our dippy, determined romantic that settlement would require a visa. Sometimes it feels like this show is just about finding new containers to keep our characters. I imagine Taylor Sheridan alone in his study, the walls bedecked with the heads of taxidermied animals he’s personally killed, on the bezel of his laptop lives a single faded post-it note on which he’s scribbled the series’ watchword in capital letters: DELAY.

Needless to say, Alex stands out on Ellis Island as she did in steerage. Her clothes aren’t worn and draped; she wears her golden curls like a halo. What happens next is a series of humiliating physical examinations that I’d rather not have seen. They made her pick up a stool; they made her undress all the way. Another passenger warns her, conveniently, that pregnant women are returned to their countries of origin and so Alex sobs through each doctor’s inspection, worrying that all this pain — this loss of dignity — is for nothing.

Although her examiners distrust the existence of a rancher husband waiting to love and keep her and her unborn child, she makes it through the medical screenings and moves on to the interview stage of this ugly beauty pageant. Another passenger warns her, conveniently, that unaccompanied females can buy their way into America, either with money, which she doesn’t have, or sex, which she won’t sell. In reality, there turns out to be a third currency: marketable skills, like literacy.

Alex is a peculiar starting point for trying to convey what it feels like to come to interwar New York because she starts out “unfree” only in the most rarefied of senses. It will be tragic if she never sees the love of her life again, but it won’t teach us anything about the world in 1923. The immigration officer assigned to her case thinks his job is to keep people out of America, and he instructs Alex to read to him from the Whitman primer on his desk, hoping to catch her in a lie. She haughtily sifts through the tome to find a passage “appropriate” to the occasion, picks the one that earnest high school seniors reliably — and to their future embarrassment — insert into graduation speeches. (Guilty!) “Dismiss whatever insults your own soul.” She also lets him know that the trollop he processed before she left lipstick on his collar. But the officer approved Alex’s visa application anyway because America used to be a real country. Gumption used to get a girl somewhere.

Sheridan writes about New York — the most urbanized population center in the world in 1923 — with the same over-the-top aversion to city slickers that he brought to his treatment of Bozeman, Montana, population 6,500. Luckily, almost as soon as Alex is released from immigration holding, she meets a sage old Black newsie who gives her the rundown on our wolf of a city. Hide your money in your shoes; keep your eyes open; don’t wander any empty streets. He teaches her to navigate New York like a mom letting her teenage daughter take New Jersey Transit into Manhattan on her own for the first time. Is it cheesy? Yes. But New York always looks good on screen, and somehow this holds true even when it’s incredibly obvious that it’s not really being filmed in New York.

Alex makes it to Grand Central to buy a train ticket to Bozeman where the well-meaning gent who sells her the ticket delivers a version of the same sermon. Hide your money anywhere but your shoes; buy a solo car; don’t wander any empty train platforms. Welcome to the Big Apple, where the people are pickpockets, the cabbies are kidnappers, and the tunnels are rapists. Unfortunately, the ticketing agent forgot to warn her off using public restrooms, and we see Alex stalked into the toilets as the episode closes. Who told her that it was safe to pee? Everyone knows that in New York City you just hold it until Boston.

Episodes of 1923 aren’t really structured like a TV show. There’s rarely a clear A story; at almost any moment, half a dozen plots compete to be the B story. It’s unclear what’s happening simultaneously or even if time progresses the same way in each theater. Does Alex land in America on the same day that Spencer takes off from Galveston with a truckload of booze for t