When Freddie Highmore accepted the role of Norman Bates in A&E’s “Bates Motel,” he faced a challenge that would intimidate any actor: reimagining a character so indelibly linked to Anthony Perkins’ iconic performance in Alfred Hitchcock’s “Psycho” (1960). Perkins’ twitchy, fragile, disarmingly boyish portrayal had defined Norman Bates in the popular imagination for over half a century. Rather than attempting to replicate this performance, Highmore took the more ambitious path of creating a Norman Bates from the ground up, one whose psychological disintegration we would witness over five seasons rather than discover in a shocking climactic reveal. The result was a character study that complemented rather than competed with Perkins’ legendary portrayal, expanding our understanding of cinema’s most famous mama’s boy and serial killer.

The fundamental difference between these performances lies in their narrative context. Perkins portrayed Norman after his complete psychological fracture, a man who had already killed his mother and assumed her personality. Highmore’s task was to show the process of that fracture—to create a teenage Norman whose potential for violence existed alongside genuine sweetness, intellectual curiosity, and desire for connection. This required a performance of remarkable subtlety, one that could suggest Norman’s darker impulses without making them so pronounced that viewers would question why those around him didn’t immediately recognize his dangerous potential.

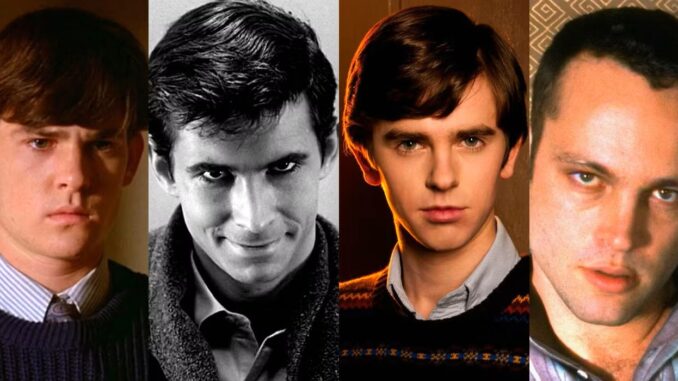

The visual presentation of the character highlights the different eras and approaches. Perkins’ Norman, with his slim ties and mid-century clothing, embodied a particular moment in American culture—the transition between the buttoned-up 1950s and the more liberated 1960s. His Norman seemed trapped in time, anachronistic even within the film’s contemporary setting. Highmore’s Norman, despite the show’s modern setting, similarly exists somewhat out of time—his neat cardigans and meticulously combed hair suggesting someone trying to embody an earlier era’s vision of propriety. Both performances use this sense of temporal displacement to underscore Norman’s fundamental disconnection from the world around him.

Perkins had to suggest Norman’s dual nature primarily through performance technique—subtle shifts in vocal pattern, posture, and facial expression that hinted at his dissociative identity disorder. The famous final scene, where “Mother” completely overtakes Norman in the prison cell, represents the culmination of this technical achievement. Highmore’s performance track allowed for a more developmental approach to Norman’s psychological fracturing. Over five seasons, viewers witnessed Norman’s blackouts, his gradual adoption of his mother’s mannerisms and voice, and his increasing inability to distinguish between reality and delusion. This extended narrative gave Highmore the opportunity to chart Norman’s psychological deterioration with remarkable precision, showing how trauma, genetic predisposition, and environmental factors combined to create the character we recognize from “Psycho.”

Both performances excel at perhaps the most challenging aspect of portraying Norman Bates: making him sympathetic despite his horrific actions. Perkins achieved this through Norman’s palpable vulnerability and social awkwardness—his famous line “We all go a little mad sometimes” delivered with such wounded gentleness that viewers momentarily forget they’re listening to a confession of murder. Highmore similarly creates a Norman whose violence stems not from inherent evil but from a fractured psyche desperately trying to protect itself. His portrayal suggests that under different circumstances—with appropriate psychiatric intervention or a less dysfunctional family environment—Norman’s story might have ended very differently.

The most significant difference between the performances lies in their relationship to the character of Norma Bates. In “Psycho,” Norma exists only as a corpse, a voice in Norman’s head, and a constructed personality he assumes. Her character is essentially Norman’s creation, filtered through his psychological distortions. “Bates Motel” gave Vera Farmiga the opportunity to create a fully realized Norma—fierce, vulnerable, manipulative, and genuinely loving. This required Highmore to develop a completely different relationship dynamic than anything suggested in Perkins’ performance. Where Perkins played against a phantom, Highmore created Norman in constant interaction with the most significant relationship in his life.

The technical approaches to the characters’ dissociative episodes differ significantly as well. Perkins famously avoided explicitly showing Norman as “Mother” until the film’s conclusion, with the character’s transitions happening off-screen. The shower scene, the film’s most iconic sequence, shows only “Mother’s” shadowy figure and hand wielding the knife, withholding the explicit revelation of Norman’s split personality. “Bates Motel” took a more explicit approach, with Highmore physically portraying Norman’s transitions into his mother’s personality. These scenes required extraordinary technical precision—Highmore subtly incorporating Farmiga’s vocal patterns and physical mannerisms without descending into parody or imitation.

Both performances received critical acclaim, though in different contexts. Perkins’ Norman Bates is regularly cited as one of the greatest villain performances in cinema history, its power deriving partly from its novelty—audiences in 1960 had never seen anything quite like it. Highmore’s portrayal, coming after decades of psychological thrillers and serial killer narratives, couldn’t rely on the same shock value. Instead, its strength lies in psychological nuance and emotional authenticity. His performance earned Critics’ Choice Television Award nominations and helped establish him as one of his generation’s most versatile actors.