The Necessary Villain in a Story of Liberation

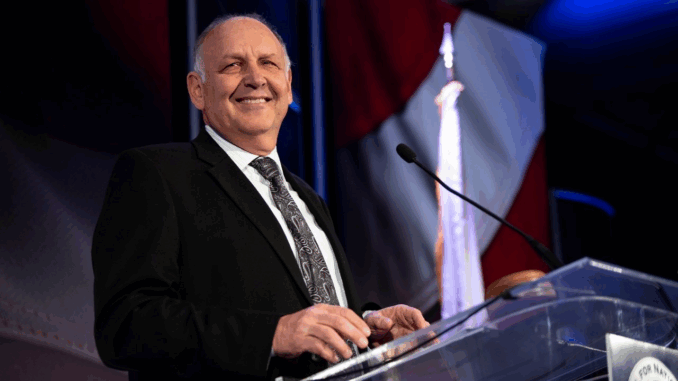

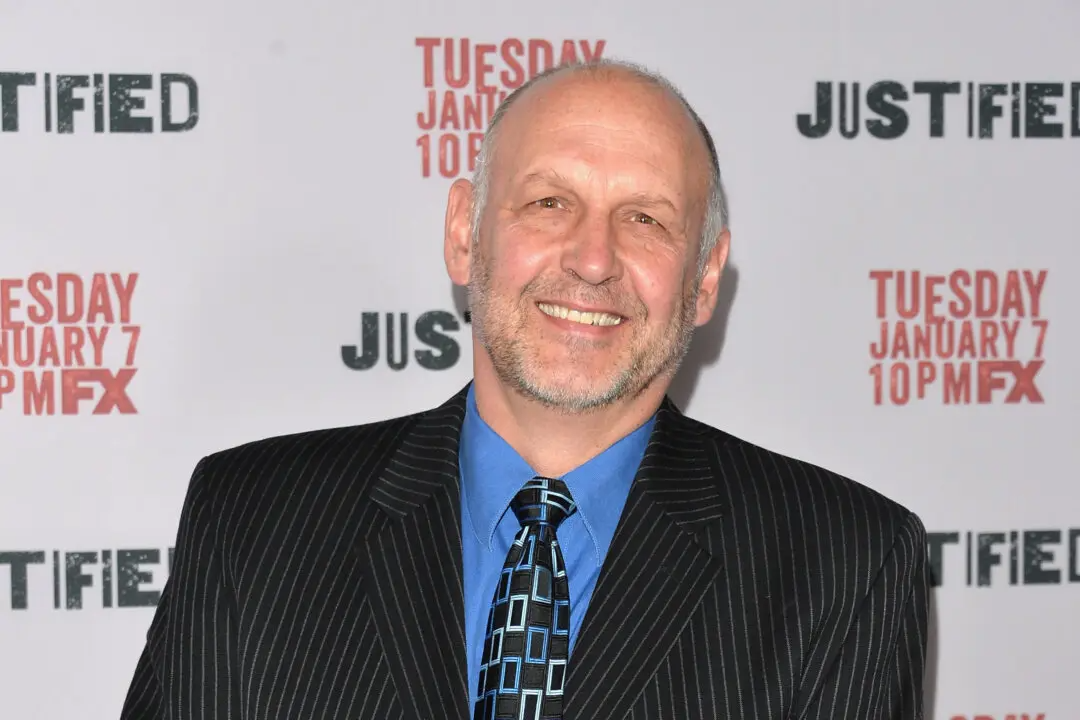

Every compelling story needs a villain—not just for conflict, but to reflect what is being fought against. In Fried Green Tomatoes, that villain is Frank Bennett. Portrayed chillingly by Nick Searcy, Frank is not just a cruel husband or a controlling father. He is a walking embodiment of patriarchal power, domestic violence, and the toxic masculinity that defines the lives of countless women in both fiction and reality.

Frank is not a character designed to be nuanced or redeemable. He is pure threat—physically, emotionally, and even legally. His presence in the film is brief in terms of screen time, but immense in terms of psychological weight. Frank’s story arc forces viewers to confront difficult truths about abuse, fear, and the limits of the legal system in protecting the vulnerable.

The Classic Abuser: Charm That Quickly Turns to Cruelty

Frank’s introduction in the film is deceptively benign. He appears as a confident, well-dressed man who courts Ruth Jamison with charm and stability. Like many real-life abusers, his outward persona masks darker intentions. Once married, Frank’s true self emerges: he isolates Ruth, controls her, and eventually becomes physically abusive.

The transition is swift and brutal. What began as a seemingly happy match becomes a prison. Ruth, who once had a bright future and close friends, is reduced to a frightened, submissive wife living in terror. The birth of her son, Buddy Jr., does not soften Frank—in fact, it makes him more possessive, more controlling. He sees Ruth not as a partner but as property, and their child as leverage to maintain control.

This depiction is tragically accurate. Many victims of domestic abuse find themselves trapped in similar cycles: fear, silence, isolation, and a sense that there’s no way out. Frank is not just a man who “loses his temper”—he is a manipulative predator whose violence is calculated and sustained.

Frank as a Symbol of Structural Injustice

Frank isn’t just dangerous because of who he is—he’s dangerous because of what the system allows him to be. In the 1930s Deep South, men like Frank had nearly absolute authority over their wives. Law enforcement rarely intervened in domestic disputes, and the courts viewed women as dependents rather than citizens with equal rights.

This is what makes Ruth’s escape from Frank so remarkable—and so risky. She doesn’t just leave a man. She challenges a structure. With the help of Idgie, Sipsey, and Big George, Ruth chooses freedom, knowing full well that Frank could use the law to drag her back. And he tries to do just that.

The film makes it clear that Frank is not going to stop. He tracks Ruth down, threatens her with legal action, and ultimately attempts to kidnap Buddy Jr. This final act is what seals his fate—and justifies, in the moral universe of the film, what comes next.

The Murder of Frank Bennett: Justice or Crime?

Frank’s murder is one of the most talked-about moments in Fried Green Tomatoes, and for good reason. It’s both shocking and deeply satisfying. In a kitchen confrontation, Sipsey kills Frank to protect Buddy Jr., and Big George helps Idgie dispose of the body—later revealed to have been barbecued and served to an unwitting crowd.

This moment has been read in many ways: as dark comedy, as feminist vengeance, as Southern Gothic justice. But above all, it is a turning point. It’s the moment the women of Whistle Stop take control of their story. Frank’s death is not random violence—it’s a reaction to years of systemic abuse, a response born from necessity when institutions failed to protect the innocent.

And it’s not lost on the viewer that it is Sipsey—a Black woman who has known both racial and gender oppression—who swings the fatal blow. In that act, Sipsey becomes the ultimate protector, defying every social expectation placed upon her. It’s one of the most powerful acts of moral resistance in the entire film.

Why Frank Had to Die

In literary terms, Frank Bennett represents the obstacle that must be removed for the protagonist(s) to grow. Ruth cannot reclaim her identity as long as Frank is alive. Idgie cannot create a new kind of family with Ruth while the threat of Frank looms. Buddy Jr. cannot be raised in safety with Frank waiting in the wings. Frank’s death clears the path for renewal, for healing, and for the redefinition of family on the women’s terms.

And so, while the film never overtly celebrates his murder, it doesn’t condemn it either. In fact, it treats Frank’s disappearance as the restoration of balance. Whistle Stop becomes a safer, freer place without him. Ruth is able to live in peace. The café flourishes. Justice, however unconventional, has been served.

The Irony of Frank’s Final Fate

Perhaps the darkest irony in Fried Green Tomatoes is that Frank, who tried to control and consume everyone around him, ends up literally consumed. His body, barbecued by Big George and unknowingly eaten by local townsfolk, becomes part of the very community he once threatened. It’s a grotesque form of poetic justice—symbolic as well as literal.

This macabre twist is not just shock value. It reflects the film’s Southern Gothic roots, where the grotesque and the moral are often intertwined. Frank’s fate is a warning: abuse and cruelty have consequences, and those consequences can come from the very people society discounts—Black cooks, elderly women, and small-town outcasts.

A Catalyst for Feminist and Communal Solidarity

Frank Bennett’s legacy in the story is not just that of a villain—he is the catalyst that brings women together in resistance. Without Frank, Ruth and Idgie may never have solidified their bond. Sipsey and Big George might not have had the chance to demonstrate their moral heroism. Evelyn, the present-day character who learns Ruth’s story, might not have found the inspiration to break free from her own emotional prison.

Frank is, ironically, the reason so many others become brave. His violence reveals the rot in the system. His threat unites the women. His death opens the door for something new. In this way, Frank becomes a necessary evil—one whose removal allows the story to evolve from one of survival to one of empowerment.

Conclusion: The Darkness That Defines the Light

Frank Bennett is not a complex villain—but that’s exactly why he works. He represents every man who has used fear as power, every system that has failed to protect women, and every relationship that becomes a cage. His character doesn’t need shades of gray because the pain he inflicts is black-and-white. Abuse is abuse. Control is control. And sometimes, the only way forward is to cut the root of the rot.

In Fried Green Tomatoes, Frank Bennett’s story is short, violent, and absolutely necessary. He is the darkness that makes the light shine brighter. And in a story about female friendship, defiance, and freedom, his absence is perhaps his most powerful contribution.