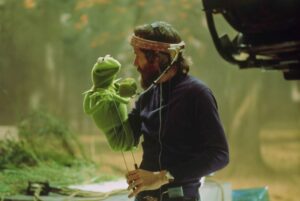

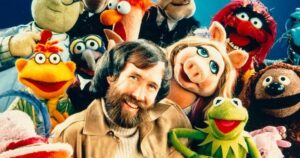

Before he became the world’s most famous puppeteer – the man responsible for The Muppets and Big Bird; and turning David Bowie into the Goblin King in Labyrinth – Jim Henson was an experimental film-maker.

In his Oscar-nominated 1965 short, Time Piece, Henson stars as a man transcending time and space, the percussive beats of ticking clocks, heartbeats and other machinery creating the rhythms for the film’s montage. In a film that takes cues from Georges Méliès and Dziga Vertov, Henson goes from playing hospital patient to Tarzan to George Washington. He was a man who could seemingly be anyone, and do anything, much like Henson himself.

“All of that experimentation, much of it didn’t really work commercially at the time,” Howard says on a Zoom call. “Much of it [was] never seen. [But] it all informed the stuff that became the huge hits and the iconic characters and scenes that we do all remember.

“He understood that you needed both worlds. That the creativity and experimentation was vital to him. That’s where his heart and soul was. But he also knew he needed to apply it somewhere that would not only pay the bills but would get people’s attention.”

Howard points to the influence Henson’s experimental shorts like Time Piece would have on his work for Sesame Street. The same playful montage and animation styles are there in those counting and alphabet videos that became foundational to millions of children. “It’s a creative life,” says Howard, “constantly exploring and discovering and then applying what you learned down the road.”

Howard, in his trademark cap and frames aesthetic, is in Cannes, where Jim Henson Idea Man is premiering. Henson himself attended the festival in the south of France back in 1980, flying in for two days on a private jet chartered by the Muppets producer Sir Lew Grade’s office. Henson wrote in his log, known as “The Red Book”, that he was at the festival talking “Lew” into a higher budget and partying on a yacht with “Liza M” (presumably Minnelli, who made a spectacular appearance as a showgirl in a film noir-inspired episode of The Muppet Show the previous year).

Howard, the former Andy Griffith Show child star turned Oscar-winning director behind Apollo 13 and A Beautiful Mind, is good-humoured and in total control of the conversation. He has a delicate but masterful way of tying any wayward question I ask back to the duty at hand: promoting Jim Henson Idea Man. That makes it hard for me to believe the veteran film-maker when he speaks of feeling the same nervous anxiousness today that he felt his first time in Cannes 36 years ago, when he premiered the George Lucas-produced fantasy film Willow.

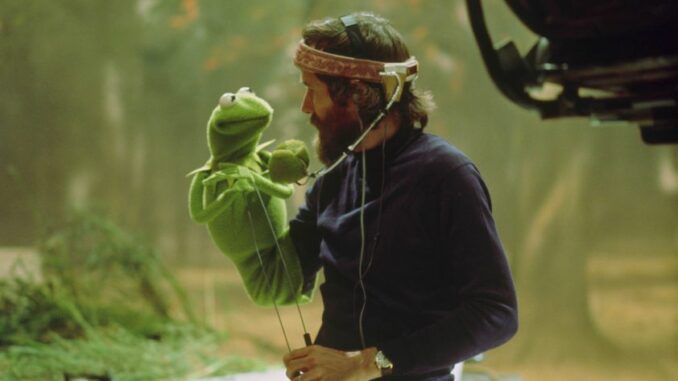

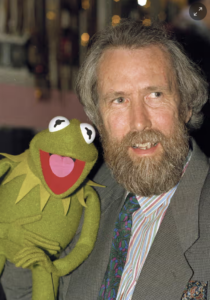

Looking back at that moment, Howard also warmly remembers that Willow featured the first credible morphing shot during a scene when a sorceress shapeshifts, comparing Lucas’s innovations to the experimentation and pioneering that Henson was known for. There’s a line to be drawn from Henson cutting out fabric from his mother’s coat to make a puppet – who would eventually go by the name Kermit – to the digital sorcery in Willow and beyond.

“When [Henson] was getting into television … the rules had not been really determined,” says Howard, looking back at a time even before he made his live television debut as a child on the series Playhouse 90. “He helped create some of those rules in the way that people in the last 15 years have been using tech to create a new language of cinema really.”

Today, the fear is that the new language is being built using AI and threatening artist jobs. Howard, in the spirit of Henson and all his experimentation, is slightly more welcoming of that technology, while agreeing it needs to be kept in check. “AI is not going away,” he says. “It’s a reality. We have to make it a tool.”

Howard also adds that he doesn’t believe AI could effectively replace artistry and ingenuity. “AI is about pulling from the world around,” he says, “especially the internet. When we put in a prompt, it feeds us the average answer. You could follow up with more prompts and so forth, but it requires interpretation to move [from] average [or] pedestrian into some area that human beings are going to find fresh and interesting … It’s almost like you want to put in a prompt and then not do what it’s suggesting. Run in the other direction.”

Howard has spent the last decade or so alternating between scripted projects like Hillbilly Elegy and Thirteen Lives and documentaries like Pavarotti and We Feed People. The Henson documentary is the first in which he gets to profile a fellow film- and TV-maker, whose craft, impulses and struggles Howard speaks to with obvious enthusiasm and empathy.

Howard talks about being drawn to telling Henson’s story after the family opened up about his story. “Their conversation about their father – but also their mother, the family, their love and affection for both of them, their acknowledgment of the foibles and the difficulties along the way – was music to my ears as a storyteller,” says Howard.

His film charts Henson’s ups and downs, and the way he deeply felt the non-starters and failures like an unrealized Broadway show or The Dark Crystal, which has since been reframed as a cult classic. The documentary leans reverent, bordering on hagiography, which is not undeserved but is also pretty much the norm, as far as authorized biopics and documentaries go nowadays.

“When you see an authorized documentary, you have to take it for what it is and recognize that,” says Howard. “Unauthorized is its own thing. It probably won’t have the intimate access that an authorized documentary will. But it may offer other insights. Then you have to decide whether you think they’re valid or not.

“The one thing we can ask, [are] the people being honest with us. Let us, the viewer, know the framework within which a documentary was made; same with literary biographies, autobiographies and memoirs.”

This is not to suggest that an unauthorized documentary would have been much more revealing as far as Henson is concerned. I don’t think anyone expected Howard and his team to ruffle around looking for dirt on the guy behind The Muppets; and even if they tried, it’s doubtful they would have discovered that he treated a sock badly or something.

“You just could see that there was nothing to hide,” says Howard. “He was a really noble guy. He was a really good example of a human being walking the Earth.”