This salon-centred tale is an unexpectedly complex study in the power of female friendship and the perspective-enhancing powers of a new hairdo

Last week I went round to my grandma’s house for a cup of tea and a catch-up. The house hasn’t changed much since I was born, and neither, to my recollection, has my grandma. Last week, as she has done every time I have been at her house before, she finished getting ready for the day by standing up in front of the big mirror in the living room, holding a huge can of Elnett hairspray aloft and, aiming it at her newly tonged curls, asking me about my love life.

It’s something that has always baffled and amused me about my grandmother. She survived having her house blown up during the Blitz, bereavement, raising two kids, the cold war, the three-day week, several car accidents … and her eldest grandchild visits her for the first time in months, and what is she thinking about? Hair and boys.

So it made sense to me that in Steel Magnolias, a film revolving around six small-town Louisiana women who gather regularly at a local beauty salon to gossip about the latest goings-on, there might be more happening beneath the surface.

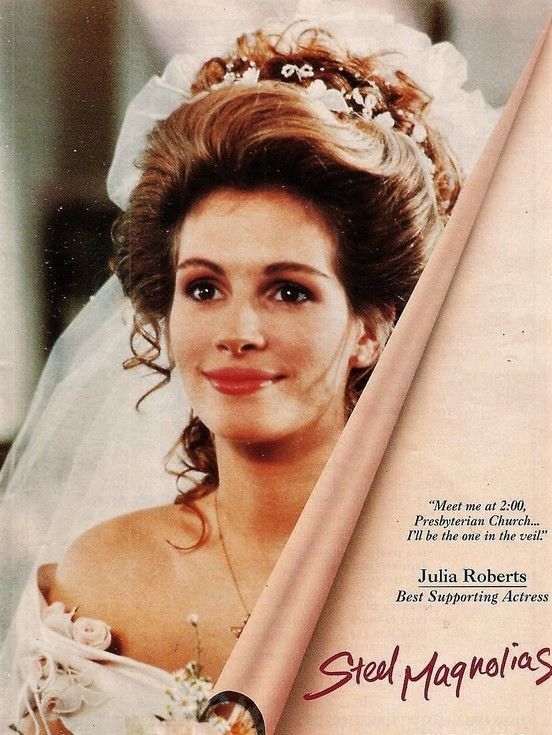

The story begins on the wedding day of spirited young Shelby, played exquisitely by a pre-Pretty Woman Julia Roberts. Sally Field is M’Lynn, the mother of the bride-to-be. At the local beauty parlour run by Truvy (Dolly Parton), the two meet new employee Annelle (Daryl Hannah). What delights the women most is anyone with a “past”, and when this gawky, evangelical new girl confesses that she “thinks” she is married, but isn’t quite sure, they draw closer and hold their breath. She explains her story, but reassuringly asserts: “My personal tragedy will not interfere with my ability to do good hair.”

Dropping pearls of southern wisdom into the exchange are Shirley MacLaine as the most cantankerous woman in town, and Olympia Dukakis, her longtime pal and the town’s former first lady, who skilfully blends torment with sarcasm.

With a foreshadowing of the tragedy to come, Shelby almost faints when she sees herself in the salon mirror. But it’s not pre-wedding jitters, it’s type 1 diabetes. She falls into a hypoglycaemic state and can only be brought around by her mother forcing her to drink a glass of juice.

The rest of her wedding day continues without a hitch, but it isn’t long before Shelby announces she is pregnant, against doctors’ advice. Her father is thrilled, but M’Lynn is too worried to share in the joy. She wants Shelby to have everything she dreams of and more, but knows she could die in childbirth because of her illness and turns to the ladies in the salon for advice. Unable to offer any wisdom, they instead suggest: “Why don’t we just focus on the joy of the situation?”

Time passes and Shelby successfully delivers a baby boy, Jackson Jr, but begins showing signs of kidney failure and starts dialysis shortly after his first birthday. The treatment is taking its toll, though, and M’Lynn offers to donate a kidney. She does so, and Shelby seemingly resumes a normal life. But upon her return home from the hospital, while the others are busy planning a wedding shower for Annelle the beautician, she is found unconscious on the porch of her house and dies later that evening.

At the moment of Shelby’s passing, M’Lynn takes her daughter’s lifeless but perfectly-manicured hand and holds it in her own: “I was there when that wonderful creature drifted into my life, and I was there when she drifted out.” At Shelby’s funeral, she stands at her graveside, grief-stricken, and pays an emotional tribute to her beloved daughter that reaches its climax when she asks for a hand mirror so she can check her appearance. “Shelby was right,” she sighs. “My hair really does look like a football helmet.”

In an otherwise chaotic universe, their primping and styling remain the constant to which they can always turn. Their lives are dominated by challenges in their marriages, their jobs, and in their health. The beauty salon is a place of frivolity where they can briefly escape and put the world to right before returning home at the end of the day with a fresh perspective and a bouncier perm. What happens in the salon is also a barometer for what happens in life. When Shelby gives birth, she decides to have her long hair cut off “to make things as simple as possible”. But when she sees herself in the mirror without her long locks, she starts to cry, knowing she has left behind part of her pre-motherhood self and must now be sensible, with a sensible hair-do to match.

Steel Magnolias has always been one of those films people automatically put in the chick-flick genre, and in many respects it is. But there’s no battle between the sexes here. The women stand by their men, and the men by their women, and they all stand by each other when life throws them a curveball. But men are not the point of this film. Steel Magnolias belongs to its women. It’s a matriarchal story in which dim-but-nice men named Spud and Drum adhere to the rules laid out by their female counterparts. The main characters are multidimensional live-wires who interact with one another without an ounce of pettiness and are hell-bent on living life to the fullest, whatever the cost. As Shelby insists when her mother tries to discourage her from having a baby: “I would rather have 30 minutes of wonderful than a lifetime of nothing special.”

This film is a true story and a brilliant depiction of friendship that manages to be witty, warm, uplifting, and, just when you thought you were safe, utterly heartbreaking. It’s also frequently laugh-out-loud funny. You’ll sympathize with Ouiser at Christmas when she asks M’Lynn: “What’s wrong with you these days? You got a reindeer up your butt?” Other memorable lines include Dolly Parton’s observation: “When it comes to pain and suffering, she’s right up there with Elizabeth Taylor,” and Clairee’s life philosophy: “What separates us from the animals is our ability to accessorize.”

The film’s tagline when it was released in 1989 was “the funniest movie to make you cry”. Off-screen, between the scenes in the salon, there are romances, feuds, births, and deaths, while on-screen the women celebrate the healing nature of friendship – and affirm, so help me, that life goes on.

The final scene sees Annelle going into labor with her own baby, whom she decides to name Shelby. But that’s life, isn’t it? It’s strange and poignant and hilarious and sad, all at once. This film captures this bittersweetness and taps into some fundamental truths about the strength that women derive from one another, regardless of their age or social background. As a group, the characters ponder what sustains us through life’s highs and lows, the relationships we build, the legacies we leave – and how we should wear our hair. All the important topics that truly bring us together.