All in the Family was the first program to genuinely reckon with the cultural upheaval of 1960s America. TV would never be the same.

Editor’s Note: Norman Lear, the prolific producer who transformed television, died on December 5, 2023, at age of 101. His career was almost too long to contemplate: Lear fought in World War II, wrote for the golden age of television in the 1950s, and was still developing shows in the 2020s. But he left his most indelible mark on television, and American popular culture more broadly, with his pathbreaking development of one show in particular, as Ronald Brownstein explained in this excerpt from his 2021 book, Rock Me on the Water.

When cbs first placed All in the Family on the air, on January 12, 1971, it irrevocably transformed television. After a shaky first season in which it struggled to find an audience, the show prospered, rising to become No. 1 in the ratings for five consecutive years, a record unmatched at the time. All in the Family commanded national attention to a degree almost impossible to imagine in today’s fractionated entertainment landscape. Archie Bunker’s catchwords—stifle, meathead, and dingbat—all became national shorthand. Scholars earnestly debated whether the show punctured or promoted bigotry.

Its success not only helped lift The Mary Tyler Moore Show, M*A*S*H, and the other great topical comedies of the early 1970s, but also cemented the idea that television could be used to comment meaningfully on the society around it—an idea the networks had uniformly rejected throughout all the upheaval of the 1960s. That legacy—the determination to connect the medium to the moment—reverberates through shows as diverse as Fleabag, Atlanta, Breaking Bad, The Wire, and countless others. The night that CBS initially aired All in the Family was the first step on the road toward the Peak TV that we are living through today.

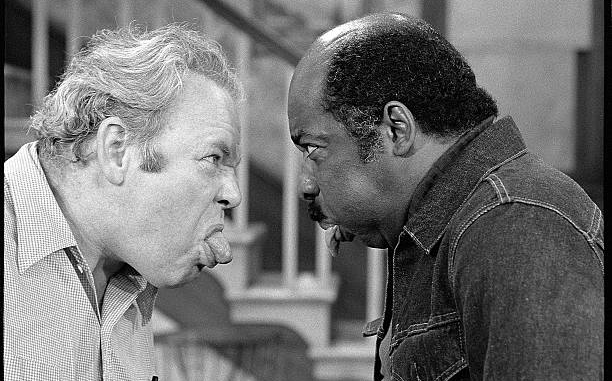

All in the Family condensed the “generation gap” of the 1960s into a single living room. It pitted Mike Stivic, a long-haired liberal, and his wife, the bubbly Gloria, against Gloria’s father, Archie Bunker, a reactionary bigot and Richard Nixon–loving dockworker—as Edith, the daffy but benevolent wife and mother, looked on. Incarnated by a stellar cast and energized by brilliant writing and directing, it became a television landmark, widely lauded as one of the greatest and most influential shows ever.

Initially, though, it was something of a miracle that All in the Family reached the air at all. Before CBS bought it, ABC had rejected it twice. And before All in the Family, shows that tried to achieve more relevance had almost all failed, mostly because they were too laden with good intentions to attract an audience. That All in the Family not only reached the air but prospered was the result of two men: Norman Lear, its staunchly liberal creator, and Robert D. Wood, the conservative president of CBS, who put it on the schedule. That act revolutionized television, but both men were unlikely revolutionaries.

Norman lear was the son of a man whose dreams dissolved quickly but whose resentments outlived him in the work of his son. Herman Lear was a small-time salesman and entrepreneur, and a fountain of dubious get-rich-quick schemes. His wife, Jeanette, according to Norman, was self-absorbed, discontented, and, like her husband, volatile. Later, they would become Lear’s early models for Archie and Edith Bunker. Throughout his childhood in Connecticut and Brooklyn, Lear’s parents immersed him in an environment of barely controlled chaos. The two of them, Lear would often say, “lived at the ends of their nerves and the tops of their lungs.” At the peak of argument, the veins in his neck bulging, Lear’s father would beat his fists against his chest and bellow at Lear’s mother, “Jeanette, stifle yourself.”

Like many children of the Great Depression, Lear found direction and structure in the military. After drifting through a few semesters at Emerson College, in Boston, he enlisted in the Army Air Force following Pearl Harbor and flew dozens of bombing missions over Germany. After a few years working as a Broadway press agent and, later, for his father, Lear made a decision that proved a turning point: He loaded his wife and infant daughter into a 1946 Oldsmobile convertible and pointed it toward Los Angeles. There, he hoped for a fresh start, but struggled to find work. He was reduced to selling furniture and baby photos door-to-door with a man named Ed Simmons, an aspiring comedy writer who was the husband of Lear’s cousin.