Before the groundbreaking debut of All in the Family, television depicted an idyllic version of American life, creating a significant disconnect from the reality many people were experiencing. In his autobiography, Even This I Get to Experience, Norman Lear observed that prior to the show’s arrival, television comedies portrayed a world devoid of pressing social issues—“no hunger in America, no racial discrimination, no unemployment or inflation, no war, no drugs.” This disconnect from real-life challenges made All in the Family a radical departure when it premiered on January 12, 1971.

When Lear and his collaborator Bud Yorkin pitched the show to CBS, the network was in search of something new—though they may not have fully grasped how transformative All in the Family would be. Just days before its debut, a review by Variety’s Les Brown indicated that CBS was struggling to resonate with contemporary audiences. The network had dominated ratings with “rustic sitcoms” catering to a rural middle-American viewership but recognized the need to “de-ruralize” and engage with more socially conscious storytelling.

The backdrop of the early 1970s was rife with social upheaval. Major events such as the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy, the Kent State shootings, and widespread protests against the Vietnam War characterized a tumultuous era. Yet, these realities were starkly absent from the television landscape, where shows like Gunsmoke and Mayberry RFD dominated the ratings. Most popular series offered little more than escapism, presenting characters entrenched in outdated values.

Despite the growing demand for relevant content, the television industry remained hesitant to embrace bold themes. For instance, a 1968 TV special featuring Petula Clark was embroiled in controversy when a sponsor objected to her touching African American singer Harry Belafonte during a duet. Similarly, The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour, known for its countercultural commentary, was canceled for pushing boundaries that advertisers found unacceptable.

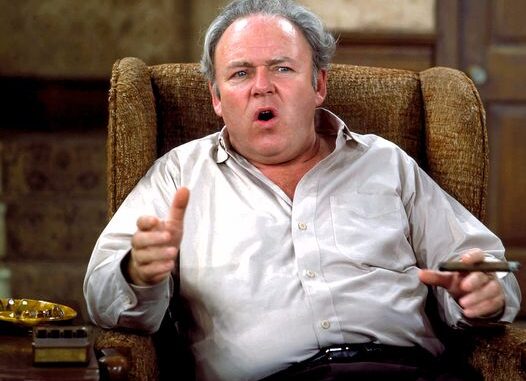

CBS executives recognized a shift was needed, and they took a gamble on All in the Family. Lear’s show would not only bring humor but also tackle serious issues head-on. The Bunker family’s living room set, complete with a television—uncommon in sitcoms of the time—symbolized a connection to the audience’s reality. For the first time, viewers heard the sound of a toilet flushing on screen, an audacious choice that signified the show’s commitment to authenticity.

These seemingly minor details served as a powerful signal that the Bunkers were relatable, reflecting the true experiences of American families. CBS’s initial fears about the show’s content were ultimately overshadowed by its groundbreaking success. Audiences embraced the series, which addressed contentious topics like racism, gender roles, and political conflict, making All in the Family not just a sitcom but a cultural phenomenon that reshaped television for generations to come. By bridging the gap between reality and representation, Lear’s creation not only entertained but also challenged viewers to confront uncomfortable truths about society.