The long-running CBS series Blue Bloods had its series finale on December 13, after fourteen seasons on the air and nearly three hundred episodes, which aired on Fridays. In a time of collapsing network television audiences, it was quite a run, and the police drama posted strong ratings until the end.

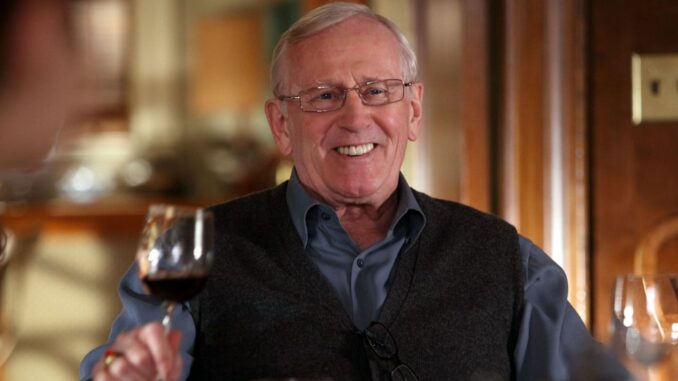

Blue Bloods is more of a family drama than a cops and robbers show. Tom Selleck stars as Francis (Frank) Xavier Reagan, the Irish Catholic police commissioner of New York City. Widowed, he lives with his widower father, Henry Reagan, who also served as the NYPD commissioner, now retired. Frank has three sons, all New York policemen, though the eldest was killed by corrupt cops before the series begins. His daughter is an assistant district attorney in Manhattan. Law enforcement is the family business.

The Reagan family is Catholic—and atypically observant. Sundays include both Mass and family dinner. The family dinner scene, included in every episode, is the most popular and distinctive. And they say grace before meals, perhaps the only family on network TV that prays together. In the closing scene of the final episode, we see the Reagans with their heads bowed in prayer.

Showrunner Kevin Wade has said that the show is about tribes—the Irish Catholic tribe, the police tribe, the military tribe (three generations of Reagans served in combat), the New York tribe. I would argue that it is more about fathers and sons, the paternal relationship highlighted by the fact that grandfather, father, and son are all widowers. Some fathers do become patriarchs, and patriarchs preside over tribes, so the two readings are compatible.

While the show began in 2010 with romantic interests for Frank, they were soon left aside in favor of stories about fathers and sons in the police fraternity—and outside the fraternity, too.

In the first season, Frank visits a mobster, Whitey Brennan, on his death bed. He offers belated condolences to Whitey, whose wife and grandson were killed in a police raid under Reagan’s command thirty years ago. Frank speaks of shared loss, the pain of the father’s heart. He then invites Whitey to make a confession—not to Frank for his crimes, but to a waiting priest for his sins. Whitey does.

Nearly a decade and a half later, in the final episode, Frank visits Lorenzo Batista in prison, a gangster played by Edward James Olmos. The commissioner needs the old man to tell him the whereabouts of his son, the prime suspect in the shooting of the mayor. The two venerable actors warily engage each other, Batista resisting Reagan’s efforts, disdaining the invitation to inform on his son. A father does not betray his own.

Having failed to get the information as commissioner, Reagan changes tack. He appeals as one father to another, telling Batista that if his son is found by the police he will likely die in a shootout. If he is arrested with Batista’s help, at least father and son can enjoy more time together, even if in prison. Reagan speaks about losing his own son in a shootout, and how he daily feels that pain. The pain of a father’s heart converts Batista. He tells Reagan where to find his son, not as a gangster who “rats” but as a father who saves.

That fatherhood is deeper even than what divides the commissioner from the criminals is a truth that Blue Bloods has returned to throughout. Fatherhood in all its manifestations—faithful, failing, fruitful, frustrated—has been a constant theme over fourteen years. And that includes spiritual fatherhood too, as priests have been frequent characters, with the archbishop of New York appearing often as one of Frank Reagan’s few true peers.

A show about fathers and sons has been particularly welcome at a time when observers from various perspectives have diagnosed masculinity in crisis. One response has been the assertion of an online “bro” culture, where domination and denigration are offered as shortcuts to (faux) manliness. In today’s media climate, Blue Bloods was like the wisdom of an elderly uncle, telling family tales of sacrifice, service, protection, wisdom, the pain of loss, and taking pride in virtue—a manliness directed toward others, not indulgence of the self. “Think like a father,” is the final advice that Henry gives to his grandson, Danny; a summation of the entire series.

Thirty years ago this past October, St. John Paul the Great published his interview book Crossing the Threshold of Hope. I was re-reading it for the anniversary, and therein the poet and playwright identified the dramatic truth that animated Blue Bloods. The oldest story, and therefore the most real story, is fatherhood:

Hegel’s paradigm of the master and the servant is more present in people’s consciousness today than is wisdom, whose origin lies in the filial fear of God. . . . The only force capable of effectively counteracting this philosophy is found in the Gospel of Christ, in which the paradigm of master-slave is radically transformed into the paradigm of father-son.

The father-son paradigm is ageless. It is older than human history. The “rays of fatherhood” contained in this formulation belong to the Trinitarian Mystery of God Himself, which shines forth from Him, illuminating man and his history.

The perennial father-son paradigm retained its power on the streets of twenty-first-century New York. Blue Bloods told that ageless story for fourteen years—fatherhood and faith on Friday night.