Setting the Scene – Whispers in the Wild

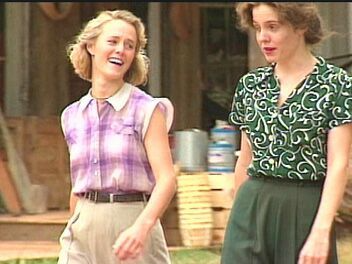

The film Fried Green Tomatoes contains many iconic and emotionally charged moments, but few scenes resonate as intimately and symbolically as the picnic shared between Ruth Jamison and Idgie Threadgoode by the river. The two women, having just begun to build a life together, sit surrounded by trees, sunshine, flowing water, and an atmosphere soaked in gentle love. It is not a moment of great conflict or overt revelation. It is, instead, a portrait of quiet revolution—the forging of a bond between two women that defies time, social norms, and even the constraints of the screen.

Set deep in the Alabama countryside, this scene offers a stillness rarely found in the film’s emotionally stormy narrative. Idgie, ever wild and unfiltered, and Ruth, gentle but wounded, create something sacred in this calm: a shared peace. The setting is not random—it’s symbolic. Nature shelters them. The river mirrors their emotions: flowing, deep, unstoppable. In that moment, it is not Whistle Stop or Frank Bennett or the rules of the church that define them—it is only their presence with one another.

Cinematic Subtlety and Unspoken Affection

From the perspective of film language, this picnic is a masterclass in subtext. There is no kiss, no declaration, no overt statement of desire or partnership. But there doesn’t need to be. Director Jon Avnet and the cinematographer use long, lingering shots to show the space between the two women closing—not just physically but emotionally. Their hands brush. Their eyes meet and hold. Ruth laughs, not nervously but freely. Idgie looks at her not with amusement, but with warmth, reverence, and perhaps fear—because love always brings vulnerability.

There’s an intimacy in how they sit, the food they share, and the way their conversation pauses not because of discomfort, but because words are unnecessary. In 1991, depicting a queer relationship—especially one in the early 20th-century South—required a kind of coded language. But this scene needs no decoding for those watching closely. It is a love scene. Not lustful, not idealized, but profound and rooted in care.

For queer audiences, especially lesbian viewers who rarely saw themselves reflected on screen in the early ’90s, this moment was monumental. It was the affirmation that love, in its quietest forms, could still be seen.

Escaping Patriarchy and Creating a Feminist Haven

Beyond the emotional and romantic significance, this picnic marks a transition in Ruth’s life. After enduring an abusive marriage with Frank Bennett—where her every move was monitored, her voice suppressed, and her safety compromised—this moment in nature is her first true taste of autonomy. She is not merely being rescued by Idgie. She is choosing to reclaim her voice, her laughter, her right to be loved without violence.

Idgie, wild from the beginning, offers Ruth not just affection but a new kind of family. The riverbank, then, becomes a feminist sanctuary—a space removed from male control and judgment. Here, they are not confined by roles as wife, daughter, caretaker, or outcast. They are simply Ruth and Idgie, sharing space and sunlight.

This picnic is a refusal to conform, a declaration—however subtle—that the traditional path is not the only one. And in that refusal lies a powerful form of resistance.

Nature as Witness and Mirror

The setting by the river is no accident. Water in literature and cinema has long symbolized transformation, cleansing, and the emotional undercurrent of a narrative. The same river that took Buddy Threadgoode’s hat and, later, his life, now becomes a place of rebirth. For Ruth and Idgie, the river doesn’t symbolize tragedy—it represents continuity. It flows forward, as must they.

The trees shield them like guardians. The soft rustling of leaves and the gentle hum of water seem to hold their secrets. There are no judgmental eyes here, no town gossip, no societal pressure. The natural world does what society fails to do: it accepts them.

This is crucial in a film that so often contrasts the chaos of human institutions—churches, courts, marriage—with the nurturing potential of natural spaces. The riverbank becomes a church of its own, where love is neither forbidden nor sinful but quietly sacred.

A Relationship Beyond Labels

One of the enduring debates among viewers and critics is the true nature of Ruth and Idgie’s relationship. The novel by Fannie Flagg leaves no ambiguity—they are lovers. The film, constrained by early ’90s studio concerns, never explicitly confirms this. But to reduce their bond to friendship alone is to ignore the emotional, visual, and narrative depth of scenes like the picnic.

Their partnership defies categorization. They are not conventional lovers, not roommates, not merely best friends. They are family. They are life partners. And the picnic scene captures that truth without the need for exposition.

In a sense, the refusal to label their relationship in the film mirrors how many real-life queer relationships have existed—outside language, outside law, but fully real nonetheless. That’s why this scene feels authentic. It trusts the audience to see what is there, without needing to be told.

Ruth and Idgie in Contrast and Harmony

This moment also illustrates the balance between the two women. Ruth, ever proper, brings gentleness, patience, and an instinct to nurture. Idgie brings defiance, energy, and a fierce protectiveness. Where Ruth calms, Idgie invigorates. Where Ruth yields, Idgie pushes forward. Together, they represent two halves of a complete emotional world.

The picnic is the moment they meet in the middle—not in crisis, not in memory, but in life. Ruth begins to laugh louder. Idgie begins to soften. In one another’s company, they find versions of themselves they didn’t know they could be.

This balance is what sustains them through the rest of the film—through Ruth’s illness, through Frank’s murder, through the slow transformation of Whistle Stop. It begins here, at the river, where they see each other not just as friends, but as soulmates.

The Scene’s Lasting Legacy

More than 30 years later, this picnic remains one of the most quietly powerful expressions of queer love in American cinema. It is a scene that countless viewers return to for solace, for affirmation, for beauty. Its legacy lies in its refusal to sensationalize. It is not built on drama or confrontation. It is built on affection, safety, and shared sunlight.

In the stillness of the riverbank, Ruth and Idgie change the course of their lives. They do not need permission, validation, or public acknowledgment. They have each other, and in that connection lies all the power they will ever need.