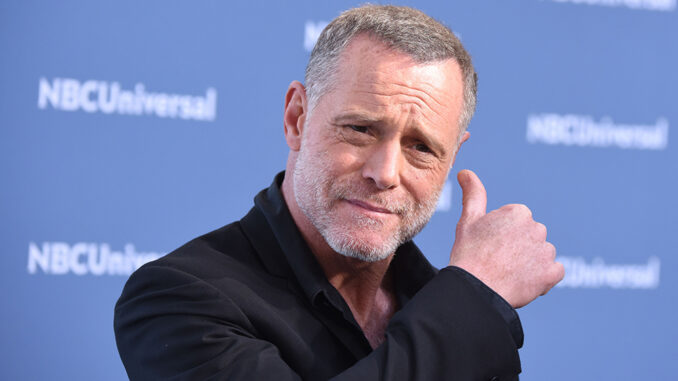

The Indelible Scars: How Beghe Kept Hank Voight Evolving Through Pain, Guilt & Change After 13 Seasons

For thirteen seasons, audiences have been drawn into the morally murky world of Sergeant Hank Voight, the grizzled paragon of Chicago P.D.’s Intelligence Unit. In an era where long-running characters often risk stagnation, Jason Beghe has performed a remarkable feat: keeping Voight a living, breathing, and terrifyingly human figure, constantly evolving through the crucible of pain, the crushing weight of guilt, and the slow, arduous process of change. Beghe hasn’t merely played Voight; he has inhabited the character’s escalating torment, ensuring that even as Voight remains undeniably Voight, he is never truly the same man he was the season—or even the episode—before.

From his initial introduction as a corrupt cop whose methods were questionable at best, Voight’s trajectory was immediately steeped in controversy. Yet, the foundational pain that would begin to reshape him truly crystallized with the senseless murder of his son, Justin. This was more than just a plot point; it was a wound that seared into Voight’s soul, irrevocably reshaping his worldview. Beghe portrayed this raw, guttural agony not with histrionics, but with a chilling, quiet intensity. The steely gaze became harder, the gravelly voice deeper with suppressed grief, and his protective instincts towards his surrogate children—like Erin Lindsay—transformed into a fierce, almost desperate, loyalty. This initial, profound pain forged a new layer to Voight: a man whose extreme actions, while still often crossing lines, were increasingly motivated by a visceral need to prevent similar suffering for others. The “ends justify the means” mantra now carried the weight of a father who had seen the ultimate price of injustice.

As the seasons progressed, guilt became Voight’s relentless shadow, an ever-present burden that slowly eroded the certainty of his moral compass. The death of Al Olinsky, his closest friend and partner, was a pivotal moment. Voight’s choices, his inability to save Al from the consequences of their shared history, left him with a deep, corrosive guilt. Beghe conveyed this not through overt tears, but through the haunted look in Voight’s eyes, the slump in his shoulders that hinted at a weariness far beyond physical fatigue. We saw Voight grapple with the cost of his own methods, the knowledge that his uncompromising pursuit of justice had directly led to his friend’s demise. This wasn’t merely pain; it was the self-recrimination of a man who believed in his own brand of justice, only to have it blow up in his face, claiming an innocent life as collateral damage. This period marked a subtle but crucial shift: Voight began to question himself, even if only in the darkest corners of his mind.

The most recent and profoundly tragic arc involving Anna Avalos brought Voight’s evolution to a new, devastating precipice, where pain and guilt converged into an abyss of self-recrimination. Voight’s misguided attempt to protect Anna, which culminated in him pulling the trigger, was a direct result of his ingrained patterns, but its outcome shattered him in a way few other events had. Beghe stripped Voight down to his rawest form. The usual impenetrable facade cracked, revealing a man consumed by a guilt so profound that he actively sought punishment, a rare admission of accountability. The silent tears, the desire for his badge to be taken, the complete lack of his usual defiant arrogance—these were not character traits Voight exhibited casually. Beghe presented a broken man, one whose pain was not just from loss, but from the horrifying realization that he had become the monster he fought, directly causing the very suffering he swore to prevent. This was the ultimate change: Voight seeing his own reflection distorted by his choices, no longer able to rationalize away the cost.

Throughout all these transformations, Beghe’s masterful performance has been the anchor. His voice, a resonant growl that can convey menace, tenderness, or profound sorrow within a single syllable, is an instrument of remarkable range. His eyes, often narrowed and intense, are an arena where internal battles play out: the flicker of doubt, the spark of rage, the deep-seated grief that occasionally surfaces. He doesn’t rely on grand gestures; instead, it’s the subtle tremor in his hand, the slight catch in his breath, the way he holds himself that illustrates the immense weight Voight carries. This nuanced portrayal has allowed Voight to evolve from a simple anti-hero to a complex, almost tragic figure, constantly navigating the tightrope between his inherent darkness and a burgeoning desire for something akin to redemption.

After thirteen seasons, Hank Voight is still the man who operates in the grey, but the shades of grey have become infinitely more complex. He is a testament to the fact that even the most hardened characters can change, not necessarily by becoming “good,” but by being irrevocably marked by their experiences. Beghe’s unwavering commitment to showing Voight’s pain, to allowing guilt to gnaw at his soul, and to illustrate the slow, agonizing process of change, has prevented the character from becoming a caricature. Instead, Voight remains a compelling, deeply flawed, and unforgettably human reflection of the enduring impact of suffering on the human spirit.