“You’re an individual, too, Ma, and you have to be free to do your own thing.” That’s Gloria Stivic counseling her mother Edith Bunker on a Season 1 episode of All in the Family, the pioneering sitcom created by Norman Lear that ran on CBS for nine seasons starting in 1971. Gloria’s advice, from the episode called “Gloria Discovers Women’s Lib” is a feel-good definition of feminism, but the episode itself contains a pretty tough-minded analysis of the kind of resistance even the most ostensibly well-meaning of men puts up in the face of actual equality.

As it happens, this was par for the course for the series. Revisiting old episodes of the show—a largely single-set affair depicting the tumultuous lives of Archie and Edith Bunker, their daughter Gloria, and her husband Michael Stivic, all living under the same working-class roof in then-present-day Queens—it’s striking how, beneath the sentimentality and the rotely conceived (but expertly crafted) sitcom humor, there’s a lot of challenging if not outright radical thinking behind its episodes.

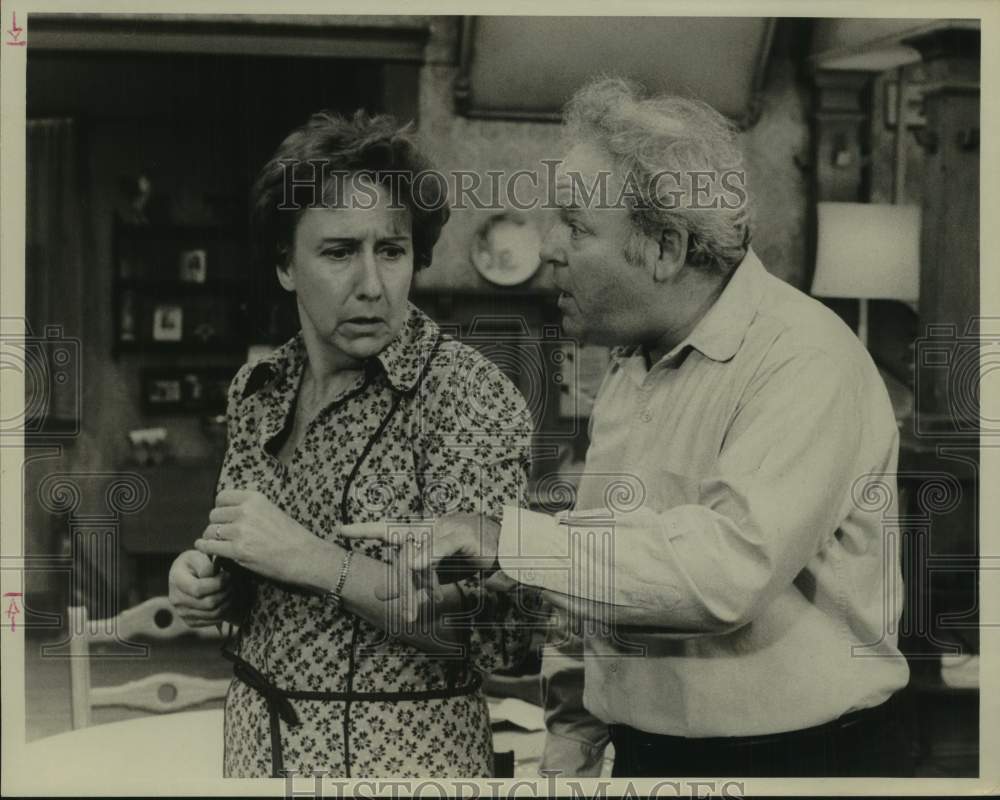

That goes for its sexual politics, maybe especially so. It’s no secret that the show’s depiction of an unequal partnership between the almost relentlessly belligerent Archie (superbly incarnated by Carroll O’Connor) and the scatterbrained and seemingly compliant “dingbat” Edith (Jean Stapleton, like O’Connor, a simply exquisite performer) added some Burns-and-Allen screwball-comedy touches to a gloss on the Ralph-Alice relationship on another classic sitcom, The Honeymooners. In the “Women’s Lib” episode blowhard bigot Archie (who comes off today like a lot of prominent males in our world who like to proclaim that they’re unafraid to speak the “politically incorrect” truth even as they reveal themselves as resentment-driven fools) proclaims his reign over the household by refusing a breakfast soufflé. But he can’t take away Edith’s satisfaction in having made one to begin with. Edith, like Alice Kramden, runs the household while allowing her husband to believe he’s its king. When Stapleton died last year, Susan Reimer, writing in The Baltimore Sun, observed of Edith Bunker, “[she] brought home [ . . . ] the nameless dissatisfaction of women in the home” that Betty Friedan had written about in the 1963 book The Feminine Mystique.

While Lear and company’s sympathies were clearly with the liberal views expressed by Mike and Gloria (Rob Reiner and Sally Struthers), the show wasn’t blind to the sexism of the then-in-decline counterculture. As early as the first season, the show depicted a working-class milieu in which pretty much all the men were largely clueless about the more crucial relationships in their lives, whether they were older men resisting the youth culture or the 20-somethings defining it.

“Gloria Discovers Women’s Lib,” co-written by Lear and veteran TV writer Sandy Stern (not to be confused with the Sandy Stern who produced Being John Malkovich, by the way), is particularly acute with respect to the brash Mike earning the “Meathead” status Archie consistently conferred on him. Responding to Gloria’s frustration over the lack of equality in the household and in general, Mike, in a monologue that sounds a lot like what we now call “mansplaining,” tells Gloria that “equality can only come about when the female partner admits her total inferiority.” His logic is, “The minute you admit to me you’re inferior, my maleness is satisfied and I can treat you as my equal.”

The writing plays up the absurdity of the idea, while the players bring the emotional commitment to make the conflict credible. Michael even tries to turn around Gloria’s complaint and make it all about himself, whining that he’s stressed about his grades. (Men: Do YOU use this tactic, even unconsciously, when you argue with your spouse? This writer will admit guilt here.) Eventually Mike defensively cries uncle, sort of: “Semantics! She’s killing me with semantics.” The episode (a highlight of both the season and the series, as has also been cited by my colleague Noel Murray of The A.V. Club) ends with a standard feel-all-the-feelings homily counseling that marriage is all about sharing (which is not untrue), but on the way there it airs out some still pertinent truths. (And it’s also pretty funny, as in an exchange in which Archie asks African American neighbor Lionel Jefferson, “You people involved in that women’s liberation?” And Lionel replies, “We’re still working on plain old liberation.”)

The dynamic stayed consistent over the course of nine seasons. While it would be a bit of an overstatement to categorize the show as an overarching critique of male privilege—for as much as Family held Archie Bunker over certain coals, he was still the hero of the series—the show deserves a great deal of credit for its never-flagging sensitivity and yes, nuance with respect to the issues it treated. The hour-long “Edith’s 50th Birthday” episode, aired in the show’s penultimate eighth season, in 1977 was canny in any number of respects. By this point in the series, Edith had become such a universally beloved character that a rape attempt against her was going to be something of a trauma for the audience, which was loath to see this character suffer. The episode was also pretty plain in its depiction of rape as a sick assertion of power rather than any kind of expression of lust. And it was heartbreaking in its depiction of the impotence the loved ones of a victim can feel in the aftermath of such an attack. That it could be all of those things while essentially retaining the comic character of the people it was depicting was, and remains, something of a miracle. The complex humanity and depth of both feeling and thought that Lear and his writers and players brought to bear on their creation is something that network television comedy, for all its ostensible progress in terms of “content,” is very much missing.