Norman Lear is 99 years old.

He’s spent much of that time building a television legacy that is unparalleled. And he’s not slowing down any time soon.

In recent years, he’s rebooted his beloved shows like One Day at a Time and allowed new audiences to rediscover his work through his specials with Jimmy Kimmel, Live In Front of a Studio Audience, recreating some of his shows most classic episodes with a new cast (Lear reveals another one of these is in the works).:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/norman-lear-1-72353c34405f46e6b3a0f2cfba8d2afc.jpg)

He’s currently working on a reboot of Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman, a show about a housewife slowly unraveling due to the influence of consumerism, which was considered ahead of its time in 1976.

These are just the latest in an illustrious career that includes having over half of the top 10 shows on the air at one juncture, a Peabody award, countless Emmys, a Kennedy Center Honor, and one of the top 20 most watched television episodes of all time.

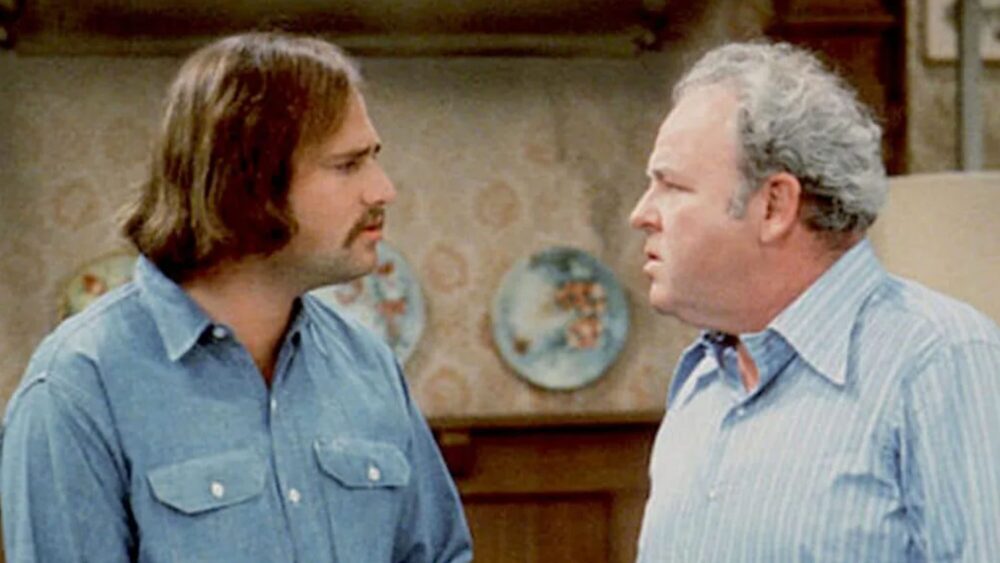

Beyond the accolades, Lear blazed a trail, making the sitcom a place where American culture and social issues were brought to the forefront through the likes of Archie Bunker (Carroll O’Connor) and George Jefferson (Sherman Hensley). He brought taboo subjects, including abortion, into American homes through his work, provoking conversation and reflection.

Now, as he celebrates his 99th birthday, his foundational sitcoms have the opportunity to reach longtime fans and new audiences alike as The Jeffersons, All In the Family, Maude, and more hit Prime Video and IMDb TV. We sat down with Lear to celebrate another spin around the sun and reflect on almost a century of work.

NORMAN LEAR: I’m on a plane tomorrow morning for our home in Vermont with all my kids and grandkids, which will take place at a farm we’ve owned for 35 years or so. It was originally [poet] Robert Frost’s farm.

When it comes to your career in Hollywood, what are your proudest of after all this time?

I couldn’t be prouder of the people who I found along the way. Because life is a collaboration and television is the collaboration of collaborations. I worked with a great many people. [My current producing partner] Brent Miller. Without whom there wouldn’t be the kind of activity we’re enjoying today. All along the way, there have been a couple of dozen fabulous writers and producers. And then the performers.

What are three things you’d like to go back and do over or do differently?

I can only think of one thing. One of the funniest people I’ve ever worked with, skipping over generations of people who made me laugh, was Nancy Walker. Nancy Walker was a major performer and comedian. And one of the funniest people there ever was. I did this show that was called The Nancy Walker Show. And I didn’t get it right. It didn’t work as well as it should have worked for this great performer. It hurts for me to say this, but since you asked if I have a regret or would like to do something again, I would love to do that again.

How did you get into the world of writing and producing comedy? One of your earliest jobs was writing for Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis.

Martin and Lewis were at the very beginning of my career. I came to California with a wife and a small child, pretty much an infant. I had a cousin Elaine here who was married to a fellow named Ed Simmons. We became friendly. He came to California to write comedy. I came to California to be a press agent, because my inspiration was the one uncle I had who used to flip me a quarter. I was a kid of the depression. I wanted nothing more than to be an uncle who could afford to flip a quarter. Ed wanted to write comedy. One night our wives were at a movie, and he was working on something and we worked on it together. When the ladies came home, I said, “Why don’t we see if we can sell this for a bunch of clubs around?” It was a bit of a monologue. Anyway, we sold it for something like 60 or 80 dollars, which was as much money as I made in a couple of days selling door to door, which is what we were doing then selling toasters and lamps and whatnot.

How did Martin and Lewis find you?

I wrote something for Danny Thomas. He was a major comic at that time. He was playing a nightclub Ciro’s, and I was standing in the kitchen at Ciro’s peeking out on the stage and watching Danny Thomas. There he is doing my little monologue and getting these big laughs, each one of which sends me to the moon, and an agent in that audience asked Thomas who wrote that. Thomas told them and the next day I got a call that had me back in New York to write a show that was short-lived, starring the Tin Man in The Wizard of Oz, Jack Haley. That was my very first television show. An episode of which was seen by Jerry Lewis. And our second job was bringing them on to television, Martin and Lewis, on The Colgate Comedy Hour.

Jumping forward in time, it famously took three pilots to get All in the Family off the ground. Why do you think the first two didn’t go? What was the breakthrough or eureka moment on the third one that the first two didn’t have?

The gods wanted me to come across Rob Reiner and Sally Struthers. The first pilot we made was terrific, and it was word-for-word the same as the second and third pilot. I had Carroll O’Connor and Jean Stapleton, but I had different young people. It was the third time we were asked to make it that I cast Rob Reiner and Sally Struthers, and bless the fact that nobody picked up the show before we found them. Because the chemistry of those four people in every direction was magic.

Speaking of which, you discovered or boosted so much talent, including Rob Reiner, Redd Foxx, Marla Gibbs, and Bea Arthur. Is there an actor you’re proudest of having brought into the spotlight?

Do you think I’m going to answer that question? (Laughs)

You love them all equally, right?

It is the truth. We’re talking about people who made me laugh to my toes. I’m fond of saying there were places in my body I didn’t know could feel laughter.

In the ’70s, you had such a spectacular run as a comedy super-producer. Was it a blur having so many shows on the air at once? How did you manage it?

I’ve likened it to a living plant of some kind. If the climate demanded another leg, I had another leg. I’m talking about the working climate. It required me to have more energy in one way or another. And I had it. I learned I had it.

Marta Kauffman has said recently Friends wasn’t more diverse because TV as a whole wasn’t, but your work is an antithesis to that. But how hard was it to get more inclusive TV made? Was there a lot of pushback from executives?

Yes. Especially after there were a couple of shows on the air and another one and another one, there weren’t that many meetings, but there was an awful lot of talking in between rehearsals of shows when executives from the network would appear. They were continuing to be afraid of this or that or the other thing. There were great people among those executives. At CBS, William H. Tankersley was the head of program practices, and we would have long fascinating talks about the contents of these shows. He represented other officers of the company, who were more tentative than he, some more brazen. He was on the stage with us and understood better what we were trying to do that day on the stage. It became a very good collaboration.

It does feel like in some ways, in terms of representation, TV took a step back in the 90s and the early aughts. Do you feel like we’re now starting to get back to the vision you had in the ’70s?

Right now Kenya Barris is brilliant. Matt and Trey who do South Park are fabulous. There are a number of people who are doing stuff that makes me laugh the way I laughed at a handful of comics across the years before I was on television.

Why do you believe television is an important or ideal space to discuss hot-button subjects and social and cultural issues?

I didn’t have to think about it when I instructed other writers that were coming to work for us to pay a lot of attention to their kids, their marriages, their families, the newspapers, everything that was going on in our country, in our schools and our workplaces and our lives. And write about that. It isn’t important that the roast is ruined and the boss is coming to dinner. It’s important that your 14-year-old is behaving in a way that makes you think he or she is terribly unhappy, and you’ve got to get to the bottom of that to help the child through it. Let’s work with real problems, there’s comedy in the foolishness of the human condition.

You’re turning 99. Your classic shows are hitting Amazon, and you have two films out, the feature film, I Carry You With Me, and the documentary, Rita Moreno: Just A Girl Who Decided to Go For It. Do you think you’ll ever retire?

I think I will be retired, but I will not retire.

With the shows now on Prime Video, where would you recommend an audience member who is not familiar with your work start?

Whatever is streaming that night.

What’s the best network note you ever got?

The best network note I ever got was I was leaving on vacation and people said, “Have a good time.”

And the worst?

“Come see me.”

Well, for those just now discovering the genius of your work, whether it’s through the shows on Amazon or a reboot or Live In Front of a Studio Audience, what do you hope they take away from it?

Exactly what audiences took away at the very beginning. I would read in many places that people that had work, the expression was “around the water cooler” on Monday would be talking about what they saw on All In the Family over the weekend. That was the thrill of thrills. That we had engaged families in a discussion of what they had just seen. Not to mention the joy of thinking about collecting families to do something together and then laugh. I don’t think there’s anything better. In my experience, there’s no more spiritual moment than an audience laughing. It’s almost as meaningful as prayer.