The Glistening Heart of Melodrama: Why Bill Condon Defends Twilight’s Camp

The very mention of Twilight often elicits one of two responses: a fervent, almost visceral defense, or an eye-rolling, dismissive scoff. For years, the saga of Bella, Edward, and Jacob has served as a cultural lightning rod, a punching bag for critics and a cherished touchstone for millions of fans. Yet, when director Bill Condon, at the helm for the final two installments, stepped forward to defend the franchise, he offered a crucial, often overlooked lens through which to view its enduring appeal: its embrace of “camp.” To mock Twilight without understanding this inherent camp is, as Condon rightly implies, to miss the point entirely.

To truly grasp Condon’s defense, one must first understand the elusive, yet powerful, concept of “camp.” As famously articulated by Susan Sontag in her “Notes on Camp,” it’s not simply bad taste, but rather a sophisticated, often ironic, aesthetic sensibility. Camp delights in artifice, exaggeration, theatricality, and a seriousness about the frivolous. It finds beauty in the outrageous, the over-the-top, and the earnestly melodramatic, often celebrating that which conventional taste would deem “vulgar” or “failed.” Camp doesn’t strive for realism; it revels in heightened reality, preferring the grand gesture to subtle nuance, the glittering facade to the gritty truth.

Twilight, in its most glistening, brooding, and dramatic form, is a masterclass in unintentional (or perhaps, semi-intentional) camp. Consider the central premise: a human girl falls in love with a 100-year-old vegetarian vampire who sparkles in the sunlight. This is not the gritty, gothic horror of traditional vampire lore; it’s an immediate subversion, an aesthetic choice that elevates the absurd to the sublime. Edward Cullen’s perpetually anguished stare, often ridiculed as wooden acting, becomes, in a camp framework, the epitome of the serious-about-the-frivolous. His internal torment, played out across his perfect, unmoving features, is not a failure of performance, but a theatrical commitment to the heightened emotional stakes of a forbidden, supernatural love.

The dialogue, frequently derided for its earnestness and lack of subtlety, further solidifies Twilight‘s camp credentials. Bella’s famous declaration, “You’re like my own personal brand of heroin,” is not meant to be a profound literary statement. Instead, it’s a line delivered with such unironic intensity that it veers into the realm of magnificent hyperbole. The love triangle itself, stretched to operatic proportions with soulmate declarations, imprinting, and near-fatal sacrifices, eschews any semblance of mundane teenage romance. Every glance is fraught with destiny, every touch a cataclysmic event. This is not realism; this is melodrama dialed to an 11, and that hyper-emotion is the beating heart of camp.

Those who mock Twilight often do so from a place of conventional critical judgment. They seek “good acting,” “believable plot,” “realistic character development”—qualities that, while valuable in many forms of cinema, are largely irrelevant, if not antithetical, to the camp aesthetic. To apply these traditional metrics to Twilight is like judging a drag show by its historical accuracy or a Bollywood film by its adherence to linear narrative. You are simply asking the wrong questions of the art form before you. The “point” of camp isn’t to be “good” in the conventional sense, but to be exaggeratedly, fabulously itself.

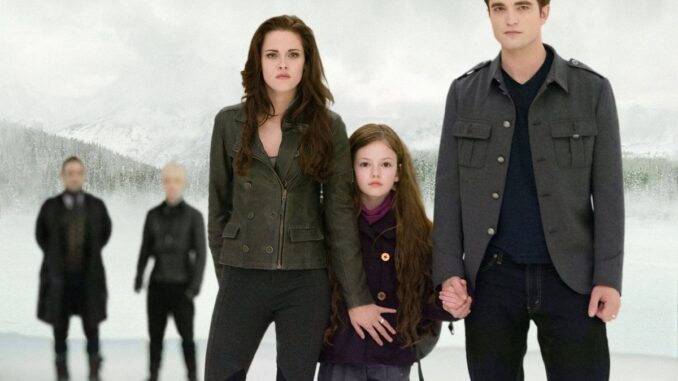

Bill Condon, stepping into a world already established by its devoted fanbase and its vocal detractors, understood this implicitly. He didn’t try to sanitize Twilight, to make it palatable to the mainstream critical palate. Instead, he leaned into its inherent theatricality. The infamous, almost dreamlike wedding sequence in Breaking Dawn Part 1, the visually stunning and utterly bonkers birth scene, and the climactic, reality-bending battle in Breaking Dawn Part 2 are not attempts at grounded storytelling. They are spectacular, over-the-top set pieces designed to deliver maximum emotional and visual impact, embracing the fantasy with a serious, unwavering commitment. He directed not just a film, but an experience, one that understands its own heightened reality.

Ultimately, Condon’s defense serves as an aesthetic Rosetta Stone for Twilight. It doesn’t ask us to declare the films “masterpieces” in the traditional sense, but to appreciate them for what they are: a vibrant, earnest, and often glorious celebration of melodrama and excess. To miss the camp in Twilight is to overlook its true, glittering genius, reducing a complex cultural phenomenon to mere “bad movies.” For those who truly get it, Twilight isn’t just a guilty pleasure; it’s a powerful, illustrative example of how the earnest embrace of the outrageous can create something enduring, passionately adored, and, yes, utterly unforgettable. It’s a testament to the fact that sometimes, the point isn’t to be serious, but to be seriously, magnificently, sparklingly camp.