Trapped in a Life of Quiet Desperation

When we first meet Evelyn Couch, she is the embodiment of midlife invisibility. Overweight, emotionally neglected, and unsure of her place in the world, she lives in the shadow of her husband Ed’s disinterest and the cultural expectations of what a “good wife” should be. Evelyn’s days are filled with diet plans, menopause brochures, and awkward moments at weight-loss seminars. Her sense of self-worth has quietly eroded over the years.

The tragedy of Evelyn’s early story is not dramatic. It is ordinary. She is every woman who’s been dismissed, overlooked, or told to smile more. And this quiet desperation is what makes her eventual transformation so compelling. Evelyn isn’t escaping abuse or poverty—she’s escaping numbness, the slow death of a soul told it doesn’t matter.

Ninny Threadgoode – The Catalyst of Change

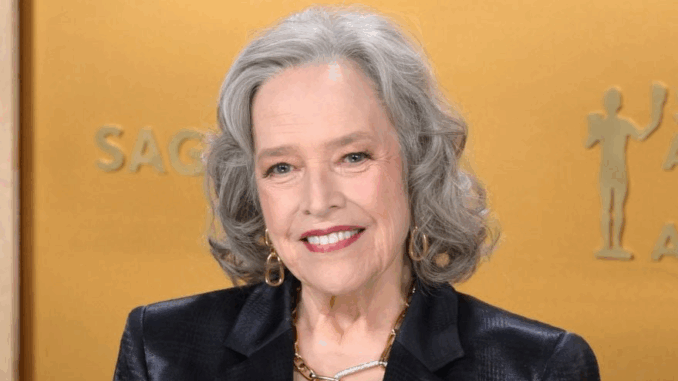

Everything begins to shift when Evelyn meets Ninny Threadgoode, a spry and spirited elderly woman at the Rose Hills nursing home. Ninny doesn’t just tell stories—she offers lifelines. Through tales of Ruth and Idgie, Ninny awakens something long dormant in Evelyn: curiosity, admiration, and eventually, self-reflection.

Ninny speaks with laughter, with tears, with urgency. Her storytelling is less about the past than it is a mirror for Evelyn’s present. The women she describes were bold, brave, and imperfect. And for the first time in decades, Evelyn begins to believe that she, too, might be more than a fading housewife.

This intergenerational friendship is the emotional spine of the film. It’s through Ninny’s stories that Evelyn not only learns history—but begins to rewrite her own.

“Tawanda!” – The Scream of Rebirth

The scene that cements Evelyn’s transformation—now iconic in film history—is her explosive outburst in a grocery store parking lot. After being rudely cut off by two younger women who steal her spot, Evelyn snaps. She doesn’t just honk her horn—she rams their car. Twice. Then screams, “Tawanda!” with the exhilaration of a woman unshackled.

The name “Tawanda” is invented, yet it becomes her battle cry, her alter ego, her symbol of reclaimed power. It’s more than a punchline—it’s Evelyn finally taking up space. After years of shrinking herself to fit societal molds, she explodes with a fury that is cathartic and deeply human.

This moment, though humorous, represents a tectonic shift. Evelyn is no longer willing to be small. She is not waiting for permission to matter. “Tawanda” is every repressed scream turned into action—and it is glorious.

Rewriting the Rules of Her Life

From that point forward, Evelyn doesn’t just change—she chooses. She begins to say no to things that don’t serve her, to people who don’t respect her, to fears that have kept her still for too long.

She starts to exercise, not to be thin, but to feel strong. She takes assertiveness classes. She confronts her husband’s indifference with new-found confidence. And most importantly, she listens to her own voice—often for the first time.

Unlike many female characters whose transformations are sparked by romantic love, Evelyn’s evolution is entirely her own. It is self-love, self-respect, and self-definition. Her journey proves that you don’t need to be young, beautiful, or dramatic to change your life. You just have to decide that you’re worth it.

Parallel Narratives – Past and Present

One of the film’s most subtle achievements is how Evelyn’s story parallels the historic narrative of Ruth and Idgie. Where Ruth escaped an abusive marriage, Evelyn escapes emotional neglect. Where Idgie defied gender norms, Evelyn defies ageism and self-doubt. And where the café became a symbol of chosen family and purpose, Ninny’s stories become Evelyn’s map to herself.

The past and present feed each other, not as nostalgia, but as continuity. Evelyn isn’t just inspired by Ruth and Idgie—she becomes their modern echo. The feminist spirit that simmered beneath the 1930s storyline erupts in Evelyn’s 1980s rebellion. It’s not a period piece—it’s a legacy.

Ninny’s Final Gift

When Ninny tells Evelyn she has no family left and no home to return to, Evelyn doesn’t hesitate—she offers her a place to live. But it’s more than hospitality. It’s Evelyn’s way of honoring the woman who helped her find herself.

By the end of the film, Evelyn is no longer the woman begging her husband to notice her. She is the woman making bold choices, forming meaningful relationships, and embracing the power of her voice. She doesn’t need to be rescued—she has become the rescuer.

Ninny may or may not be Idgie, as the film teasingly suggests. But it doesn’t matter. She was the spark Evelyn needed. And Evelyn carries that flame forward, lighting her own path and offering warmth to others.

A New Kind of Heroine

Evelyn Couch is a rarity in cinema: a middle-aged woman whose story isn’t centered around motherhood, romance, or tragedy—but around transformation. She is not polished or idealized. She is messy, funny, insecure, and real.

Her journey affirms that personal revolutions aren’t always loud or immediate. Sometimes, they begin with a story. A friendship. A moment in a parking lot. And sometimes, the most profound form of resistance is simply to say: “I matter.”

Evelyn doesn’t burn down the world. She rebuilds herself. And in doing so, she reclaims joy, agency, and purpose.

Conclusion: The Power of Becoming

By the end of Fried Green Tomatoes, Evelyn Couch is not a new woman—she is her true self, finally unleashed. She teaches us that change is possible at any age, that strength comes in many forms, and that even the quietest lives can hold revolutions.

She is Tawanda, yes—but she is also Evelyn. Brave, blooming, and wholly her own.