Fried Green Tomatoes is often remembered for its comforting Southern setting, heartwarming relationships, and slice-of-life storytelling. But beneath the quaint charm and nostalgic cinematography lies a powerful feminist narrative that challenges traditional gender roles, redefines female agency, and honors women’s resilience across generations. Through its multi-generational storytelling and deeply nuanced female characters, the film becomes a quiet yet profound revolution — set not in protest rallies, but in kitchens, cafes, and whispered conversations between women.

Southern Women and the Cage of Convention

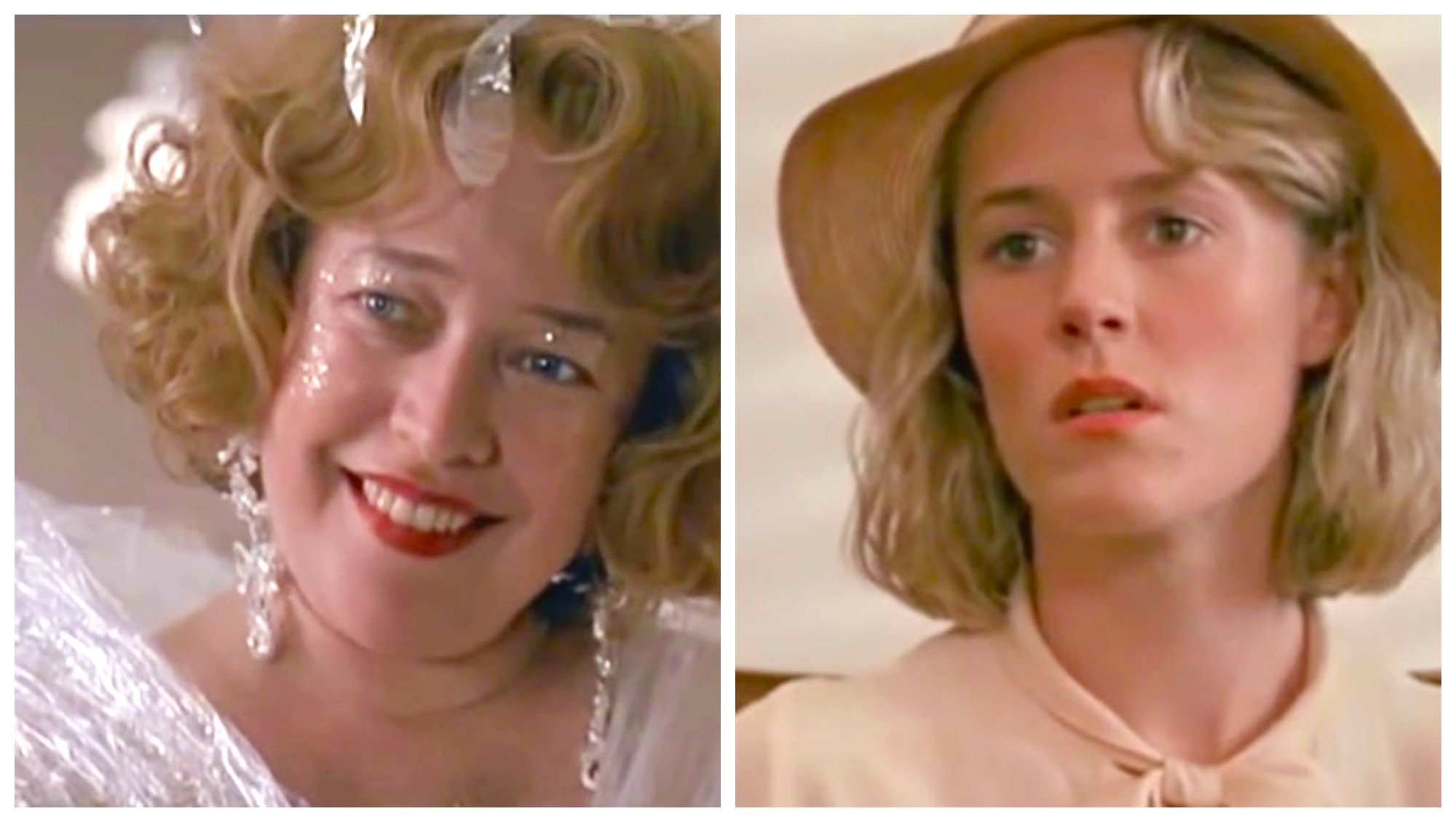

Set in both the 1920s and the 1980s, Fried Green Tomatoes presents two very different yet equally repressive eras for women. In the flashbacks, Ruth Jamison and Idgie Threadgoode face a deeply patriarchal society where women are expected to be submissive, domestic, and dependent. Ruth is initially trapped in a violent marriage with Frank Bennett — a symbolic representation of male dominance and societal control. Idgie, on the other hand, rejects conventional femininity altogether, preferring trousers, adventure, and whiskey to church socials and sewing circles.

In the modern-day storyline, Evelyn Couch represents a different kind of confinement. She is not abused, but ignored and devalued — the classic case of a housewife suffering in silence. Her husband doesn’t physically hurt her, but his indifference slowly erodes her self-worth. Evelyn’s story shows how even in more “progressive” times, women often remain stuck in roles that deny their individuality and strength.

Female Friendship as Feminist Resistance

What makes Fried Green Tomatoes revolutionary is its radical centering of women’s relationships. The most powerful actions in the film arise not from confrontation with men, but from women finding strength in each other. Idgie and Ruth’s relationship — deeply emotional, possibly romantic — offers an alternative model to heteronormative love. They build a life together on their own terms, opening the Whistle Stop Café as both a business and a sanctuary.

This friendship functions as a form of feminist resistance. In the Jim Crow South, running an integrated café where Black customers are treated with dignity is already an act of quiet rebellion. But more than that, the café becomes a space free of male dominance — one where women can make decisions, build community, and protect each other.

Likewise, the friendship between Evelyn and Ninny becomes a catalyst for Evelyn’s transformation. Ninny’s stories of female courage inspire Evelyn to rediscover her voice, her anger, and her independence. Their intergenerational bond shows how women’s stories, when shared, can serve as tools of empowerment and change.

The Feminist Symbolism of Food and the Café

Food in Fried Green Tomatoes is never just sustenance. It is comfort, identity, culture — and power. The act of feeding others becomes symbolic of nurturing, not just in the maternal sense, but in the revolutionary one. The Whistle Stop Café, run by women, becomes a place of safety for outsiders: Black customers, abused women, hungry travelers.

By reclaiming a traditionally feminine domain — the kitchen — and turning it into a business and social haven, Idgie and Ruth redefine what it means to be a “woman’s place.” Their café is not a prison; it’s a launchpad for independence. The frying of green tomatoes becomes emblematic of turning simple, undervalued things into something bold and sustaining.

The Evolution of Evelyn Couch: A Feminist Awakening

Evelyn’s transformation is perhaps the clearest feminist arc in the film. When we first meet her, she is invisible — both to her husband and to herself. She tries every diet, every gimmick, every polite approach to be noticed, to matter. But as she listens to Ninny’s stories, something begins to shift. She starts asserting herself, both emotionally and physically (the “Towanda!” scene is an unforgettable declaration of feminine rage).

Her journey reflects the real-life awakenings many women experienced during the feminist movements of the 1960s-80s. Unlike Idgie and Ruth, Evelyn doesn’t fight racism or domestic abuse, but she battles self-erasure — a fight just as difficult and vital.

Motherhood, Non-Motherhood, and Choice

Another feminist aspect of Fried Green Tomatoes is its diverse portrayal of motherhood. Ruth is a biological mother; Evelyn is childless but finds meaning through nurturing relationships. Idgie, too, takes on a maternal role in caring for Ruth’s son, Buddy Jr. But the film never suggests that womanhood must equal motherhood. Instead, it celebrates different ways women can express care, protection, and legacy.

What makes this portrayal powerful is that it doesn’t shame women for choosing — or not choosing — traditional roles. It allows for fluidity. It respects choice.

Feminist Storytelling: Women Writing Women

It’s also worth noting that Fried Green Tomatoes was based on a novel by Fannie Flagg — a female author who infused the story with layers of gender commentary and Southern nuance. Flagg’s voice is key to the film’s authenticity. The screenplay, co-written by Flagg and Carol Sobieski, keeps the focus tightly on female experiences, steering clear of male savior tropes or romantic clichés.

In a film industry often dominated by male perspectives, Fried Green Tomatoes is rare: it gives women the pen, the camera, and the mic — and lets them tell their own stories.

Conclusion: Feminism in Aprons and Overalls

Fried Green Tomatoes doesn’t shout its feminism — it simmers it. It’s a film where radical change happens in gardens, cafés, and whispered memories. Where strength looks like two women starting a business in a hostile world, or an older woman helping another find her voice after decades of silence.

Through its layered characters and quietly subversive narrative, Fried Green Tomatoes proves that feminism doesn’t always need a picket sign. Sometimes, it just needs a plate of fried green tomatoes and the courage to say: “No more.”