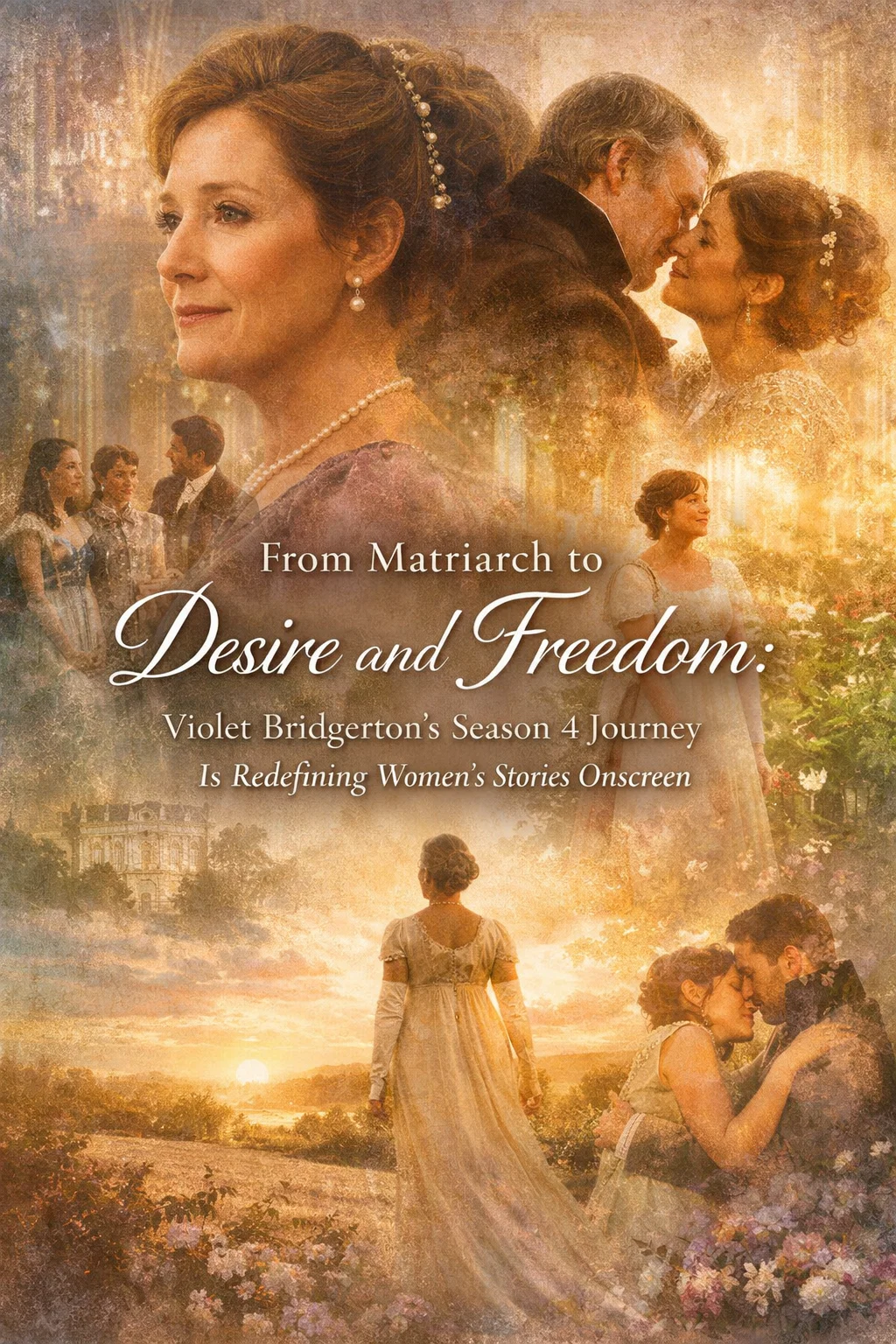

Violet’s journey in the fourth season of Bridgerton is a masterclass in reclaiming a body that has long belonged to everyone but her.

It’s not often that I find myself quoting Bridgerton in everyday conversation, but this week saw me do exactly that – albeit without realising what I was doing at first.

“It is not selfish to want something for yourself. You have a right to be as happy or as free as you would like.”

As soon as the words tumbled from my mouth while I was mid-hype-girl speech to a fellow mum (who was worrying that taking a morning for herself would be seen as self-involved), I knew that I’d heard them before. It took me a minute, though, to pin down exactly where: they’d been uttered by none other than that most silver-tongued of philosophers, Violet Bridgerton.

Now, don’t get me wrong: the fourth season of Netflix’s bodice-ripping series belongs to Benedict and Sophie’s Cinderella story. It had all of us hooked from the very moment he tugged off her silk glove and pressed a kiss against her inner wrist in that moonlit garden.

For me, though, the true revolution is happening in the background via the story of Violet Bridgerton, a woman who has spent decades as the moral and emotional scaffolding for eight children, finally rediscovering her libido and seizing pleasure for herself. Hell yes!

Her awakening plays out throughout the season in a series of tiny moments. There’s the fleeting scene when Violet forces herself to confront her body in the mirror, for example, where she peeps under her robe, then drops it to the floor.

Her reaction is swift – a glimmer of a smile, the quirk of an eyebrow – but abundantly clear: Violet isn’t looking at herself through the eyes of the Bridgerton matriarch, but as a woman reclaiming territory. For years, her body has been public property; a landscape for others to traverse, to cling to, to drain. Or, as she puts it; “My children are marvellous, but… they are like dogs on a fox, and I cannot be their fox.”

Then, there’s her confession to a certain Lord Marcus Anderson, which hits like a bolt of lightning: “I am mature now. My body… I am different now. All of me is different now. And how will that be? I want it. I want to be seen and touched. By you. [But] I am nervous.”

Now, I haven’t had quite as many children as Lady Bridgerton, true (and not to get too Love Actually about it, but eight is a lot of kids, Violet), but I still felt every second of that speech. There is a specific kind of grief that comes with motherhood: the fear that your body has become a sum of its parts. Too changed from what it was. Softer. Less defined. Blurry. A milk dispenser. A pillow for tiny people to lie upon when they can’t sleep. A human-sized tissue for them to wipe their noses on, apparently. A sleepless bundle of nerves and aches that I distinctly remember not being there before I squeezed any human beings out of my uterus.

You’ve shown me yourself. I’m grateful

Society has a very specific ‘shelf life’ for a woman’s sexuality. We are allowed to be the ingénue, the blushing bride or the fertile mother. But once the nursery is full, so to speak, the narrative usually demands we retire into a life of wise counsel and sensible cardigans. We are expected to become the fixed point around which everyone else’s desires orbit, while our own are packed away in the attic like last season’s outmoded pelisses.

Violet’s story, however, refuses to be mothballed. And there is something profoundly radical about seeing a woman admit that she is hungry – not for a ‘companion’, but for the specific, electric heat of being wanted.

There is something similarly mesmerising about Lord Marcus Anderson’s response: “I want you. If possible, I want you more,” he tells her softly. “You’ve shown me yourself. I’m grateful. We need be in no hurry. I am content as long as I am in your presence.”

Dearest gentle readers, isn’t that all anyone wants to hear? To be acknowledged as desirable but given the time and grace to figure out what’s next in their own good time? In a world that too often treats a mother’s ‘changed’ body as a tragedy to be overlooked, Marcus validates the Violet who exists now. He isn’t looking for the girl she was when Edmund first swept her off her feet; he is looking at the woman she has fought to become.

It made me realise that my own ‘sleepless bundle of nerves’ isn’t a ruined version of my former self. It’s a version that has survived, lived and earned its right to be seen. We don’t have to choose between being the scaffolding and the spectacle; instead, we can be the woman holding the family together and the woman dropping her robe in the candlelight, finally ready to let someone else carry the weight for a while.

As I told my friend during that aforementioned hypegirl speech: it isn’t selfish to want things for yourself. In fact, after everything our bodies have done for everyone else, perhaps the most selfless thing we can do is finally enjoy the skin we’re in.

Because if Violet can find her ‘pinnacle’ again after eight children and a lifetime of mourning, surely there’s hope for the rest of us. Milk-stains, tissues, sleepless nights and all.