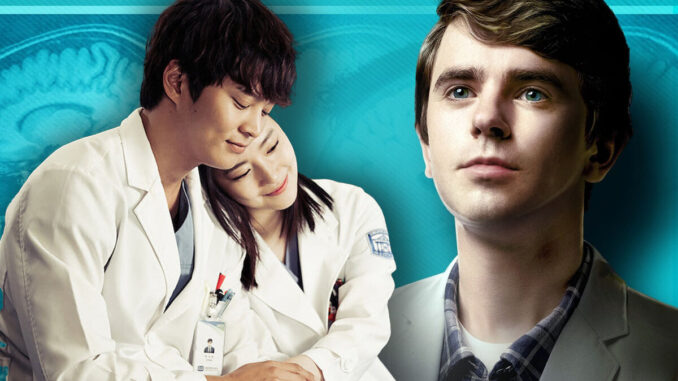

When The Good Doctor first aired on ABC in 2017, it seemed destined for greatness. Backed by House creator David Shore and adapted from the hit 2013 Korean drama of the same name, the U.S. version had the perfect ingredients: a compelling lead, emotional cases, and a built-in international fanbase. For a while, it worked — the show pulled strong ratings and made Freddie Highmore a household name. But somewhere between the seasons, The Good Doctor lost the magic that made its Korean predecessor unforgettable.

To understand why, you have to look at what the K-Drama did differently. The original Good Doctor wasn’t just about medicine — it was about healing as humanity. Park Si-on, played with aching sincerity by Joo Won, wasn’t simply a savant surgeon; he was a wounded soul navigating a system that didn’t believe he belonged. Every episode felt personal — less procedural, more spiritual. The stakes weren’t just life and death, but acceptance, dignity, and love.

The U.S. remake, in contrast, leaned heavily on formula. Its early episodes dazzled with emotional resonance, but soon the hospital drama began to feel procedural — another case of the week, another moral lecture neatly wrapped in forty-three minutes. The series slowly shifted from character-driven storytelling to a rhythm of predictable conflicts and sentimental resolutions. The emotional subtlety of the Korean version was replaced by exposition, the kind that tells you to feel rather than letting you discover it.

Freddie Highmore’s performance as Dr. Shaun Murphy remains extraordinary — nuanced, fragile, and deeply intelligent. But the writing around him often boxed the character into repetitive arcs: struggle, breakthrough, relapse, repeat. The show preached empathy yet sometimes forgot to practice it in its own pacing. Shaun’s autism, initially portrayed with care and complexity, too often became a narrative device instead of an evolving lens into human connection.

Meanwhile, the Korean version understood restraint. It knew when to stay quiet. It trusted silence — the pauses between words, the glances between colleagues — to tell more than dialogue ever could. The result was a story that felt both intimate and universal, grounded in cultural humility and emotional authenticity.

There’s also a tonal difference that Western television rarely bridges: The Good Doctor (Korea) was inherently hopeful. It treated kindness as power. The U.S. version, in trying to add grit and realism, sometimes lost that warmth. It became a story about performance — doctors performing heroics, emotions performing for ratings — rather than genuine growth.

Ironically, where the U.S. show succeeded commercially, it failed artistically. It lasted seven seasons, reached millions globally, and gave autism representation a major platform — achievements that matter deeply. But when fans of the original tune in, they often feel what’s missing: the quiet empathy that once made The Good Doctor more than a medical drama.

In the end, the failure isn’t total — it’s tonal. The Korean version made us cry with its characters. The American one often made us cry for them. One feels lived-in; the other, manufactured. Both tried to show us what it means to be good. Only one truly understood it.