When viewers tuned in for the final episode of All in the Family on April 8, 1979 (44 years ago this month), there was no big send-off, no big wrap-up, no celebration — just a simple, sweet episode in which an ailing Edith Bunker puts in a lot of work to help her husband, Archie, organize a party at his tavern. Archie realizes all she’s done, and they share an uncharacteristically tender moment together. And then it was over.

But in that quietude there was history. The groundbreaking social-issues comedy ran for nine seasons, was the No. 1-rated show for five of them, won 21 Emmy® Awards (including four for Outstanding Comedy Series), spun off five other sitcoms — and along the way arguably changed what television was, what it looked like and what it could be.

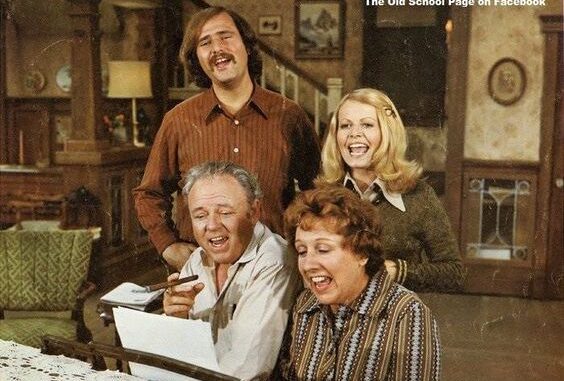

All in the Family debuted as a midseason replacement on CBS, then the dominant TV network, on January 12, 1971. It focused on an average working-class white guy, a dockworker named Archie Bunker, who lived in an average rowhouse in an average neighborhood in Queens, New York, with his dutiful homemaker wife, Edith; their adult daughter, Gloria, and her liberal husband, Mike Stivic. Archie and Edith were old-fashioned folks — the show opened each week with the two of them seated at the piano, singing its famous “Those Were the Days” theme song about simpler times gone by — and the world was changing around them. Archie, a proud bigot, hated that change, and the show’s comedy derived from his resistance to everything that the ’60s and early ’70s represented. Over its run, All in the Family dealt with racism and women’s rights, the Vietnam War and homosexuality, and countless other topics that were then roiling the country.

What made All in the Family so transformative was that it was the first time any of that change invaded prime-time entertainment. In fact, before its first episode, CBS felt compelled to air a disclaimer: the show, the network said, “Seeks to throw a humorous spotlight on our frailties, prejudices and concerns. By making them a source of laughter we hope to show — in a mature fashion — just how absurd they are.”

When All in the Familydebuted that Tuesday night in January, the shows preceding its 9:30 p.m. time slot seem in retrospect to have been lifted from another era. Its lead-ins were The Beverly Hillbillies, Green Acresand Hee-Haw. This, in a country that was reeling from assassinations and antiwar protests, racial violence and the counterculture.

CBS had realized just how out of step it was, and the network’s president, Robert D. Wood, was looking for new shows that could help it attract a more sophisticated, urban audience. (Just before All in the Family‘s debut, a Variety writer had described the network’s programming as “rustic sitcoms” for “the rural middle-American viewership.”) The producers Bud Yorkin and Norman Lear, who would go on to be a legendary force in television and a lifelong progressive activist, had adapted a BBC series called Till Death Us Do Part for ABC, casting Carroll O’Connor and Jean Stapleton as Archie and Edith. When ABC declined to pick up the series, it was a perfect fit for Wood’s new vision for CBS.

However, CBS was worried it was too different from the usual fare. The network did little to publicize the new series, and its first episode notched a distant third place in the ratings (back when there were only three networks). But people began to notice, and by the Emmy Awards that May, the All in the Family cast was featured in an opening skit, and the show took home three awards, including Best Comedy Series. It was also, by the end of the season, No. 1 in the ratings.

All in the Family didn’t just bring the real world into television shows — it also made television shows look more recognizably like real life. It was one of the first shows to prominently display a television set in the living room, like normal families did, and it famously included the first audible (if not visible) toilet flush in television history.

But, most important, by bringing the real world to the boob tube, Lear’s influence has lived on for a half-century. It happened first in his own shows, like All in the Family spin-offs Maude(about Edith’s women’s-libber favorite cousin, played by Bea Arthur, which famously included an episode about abortion) and The Jeffersons (about the Bunkers’ onetime neighbors, a well-to-do Black couple who moved to the wealthy, white Upper East Side). It continued through 1980s with “very special episodes” and into beloved, satirical cartoons that take on every taboo. And his spirit remains strong in our prestige TV era, whether the shows are about transgender retirees or the burdens we place on our urban schoolteachers.

Lear himself may yet have more up his sleeve. On the occasion of his 100th birthday last summer, he told People magazine that he has 23 new projects in the works.

Click the social buttons to share this content with your friends and colleagues.

The opinions and points of view expressed in this content are exclusively the views of the author and/or subject(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of MediaVillage.com/MyersBizNet, Inc. management or associated writers.