The following feature is adapted from LIFE’s special edition All in the Family: TV’s Groundbreaking Comedy, which recently celebrated its 50th anniversary.

Audiences watching TV on Tuesday, Jan. 12, 1971, probably wondered about the unusual disclaimer running ahead of All in the Family, letting them know that the new CBS program planned to throw “a humorous spotlight on our frailties, prejudices, and concerns.” The show then opens with Carroll O’Connor and Jean Stapleton, as their characters Archie and Edith Bunker, sitting side-by-side at a doily-draped spinet and singing the show’s theme song, “Those Were the Days”:

Boy, the way Glenn Miller played.

Songs that made the Hit Parade.

Guys like us, we had it made.

Those were the days.

The song brought to mind the comforting prewar music of the big bands. But while the elegiac piece by the composer/lyricist team of Charles Strouse and Lee Adams elicited memories of better days, it also had a whiff of the caustic social satire of The Threepenny Opera (by the German writer/composer duo Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill), as Archie evoked the era of Herbert Hoover, whose conservative presidency ushered in the Great Depression.

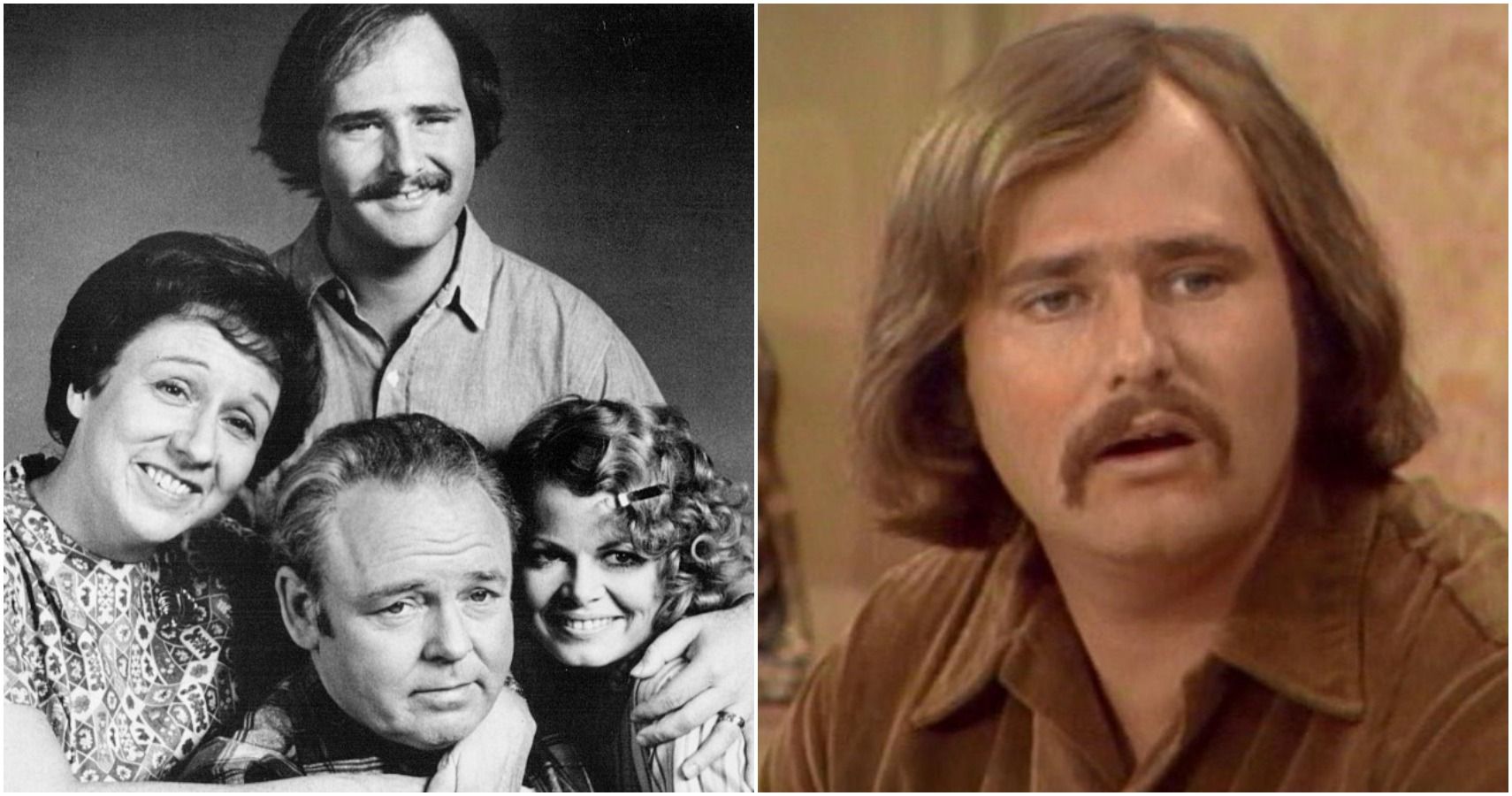

Viewers’ confusion quickly took hold. When Archie and Edith return from church to their home at 704 Hauser Street in Queens, New York, Edith tells him how horrified she is that he has just cursed the minister for his sermon. Gloria and Mike try to lighten the mood with an anniversary lunch they have prepared for the couple. But as the four sit down to celebrate, it takes no time for Archie to complain about the “Hebes,” “spics,” “spades,” “pinkos,” and atheists who have co-opted society, all the while tarring Edith as a “silly dingbat” and spewing his bile at Mike by calling him a “meathead.”

Most people had never seen anything like Archie Bunker (at least on their televisions)—a bullet-headed loading-dock worker who swills beer, smokes cheap cigars, and has a chip on his shoulder as wide as the Queensboro Bridge. Impatient, conservative, proudly bigoted, and malaprop-prone—he would say things like “Let him who is without sin be the rolling stone”—Archie was the furthest thing from the neighborly folks on Hee Haw, or for that matter, the paternal Jim Anderson on the 1950s show Father Knows Best, who sold insurance in his suburban paradise of Springfield.

CBS so worried about viewers’ responses to Archie, that they manned their phone lines with additional operators to field the expected barrage of angry callers. Few calls came, though, and only 15 percent of viewers welcomed the Bunkers into their living rooms. It wasn’t quite the tectonic reception creators Norman Lear and Bud Yorkin had hoped for. The press also had mixed takes on their show. While Variety called it “the best TV comedy since The Honeymooners,” LIFE magazine’s John Leonard branded it “a wretched program.”

For 13 weeks that spring Archie served up outrages like a rancid blue plate special, as Lear offered up issues never before printed in TV Guide’s menus. In the fourth episode, Archie decries Mike and Gloria’s ascot-wearing friend as a “fairy,” only to be stunned to learn that his linebacker pal Steve is gay. In another episode, Gloria gets pregnant and then miscarries.

Lear, who as a child felt powerless to respond to the hate he heard spewing from Father Charles Coughlin’s radio broadcasts, used his video soapbox to explore the racial divide, with the show being the first to display it for laughs as Archie deals with Italian neighbors, Jewish lawyers, and Puerto Rican New Yorkers. In the first episode audience members meet Lionel Jefferson, played by Mike Evans, the show’s main African American character, who needles Archie’s prejudices, and who, according to director John Rich, could “tease Archie in a way that is not offensive.”

Race proved to be an important issue throughout the series—one of the regular epithets Archie slings at Mike is “dumb Polack.” And just a few episodes into the first season, Archie is horrified to learn that a Black family has bought 708 Hauser Street, complaining that “the coons are coming.” Archie then realizes that Lionel’s parents, George and Louise, purchased the home. And George, the Jefferson patriarch, is as bullheadedly bigoted as Archie.

Characters like Archie, pining for the past, might have been new to television, but he was not a stretch in 1971. The year before, a violent confrontation broke out in New York’s Wall Street area as construction workers chanting “All the Way, USA” clashed with antiwar demonstrators in what became known as the Hard Hat Riot. And that July, Joe, a film about an outraged welder (played by Peter Boyle) who abhors the counterculture, hates that a “colored” family moved into his Queens neighborhood, and heads to a commune to slaughter its inhabitants, opened to critical and box office success.

With All in the Family, the discord on the nation’s streets had finally leaped from the nightly news to the nightly entertainment. People couldn’t help but cringe and take notice. And notice they did. That May, the show’s four leads introduced the Emmy Awards in a skit that depicted them watching the award ceremony from their Hauser Street living room, with Archie asking, “I wonder if Duke Wayne is up for anything. Probably not, with all them left-wingers runnin’ the whole of TV.” While John Wayne wasn’t up for an award, those “pinkos” working in TV bestowed three statuettes on All in the Family, one to Stapleton as best actress in a comedy series, and two to Lear, one for outstanding new series and another for outstanding comedy series.

Unexpected attention also came their way. Four days after the Emmys, Nixon was caught on his Oval office tapes talking with his chief of staff, H.R. Haldeman, and domestic policy chief, John Ehrlichman, about All in the Family, with the President praising Archie as “a hard hat,” and Haldeman noting that the show seeks “to downgrade him and make the square hard hat out to be bad.”

The show was having such an impact on viewers that school teachers searched for guides on how to teach their students about bigotry. Criticism was at times quite severe. When O’Connor attended church soon after the show premiered, fellow congregants hissed him. Laura Z. Hobson, who had written Gentlemen’s Agreement, a novel about anti-Semitism that was made into a 1947 Academy Award–winning film, wrote in September in the New York Times: “I don’t think you can be a Black-baiter and lovable, or an anti-Semite and lovable.” Lear dismissed Hobson out of hand, writing in that paper, “In what vacuum did you grow up? Not a father, brother, uncle, aunt, friend, or neighbor who was both lovable and bigoted?”

While foulmouthed, Archie was weekly put in his place and shown to be wrong. Even so, he gave voice to the thoughts of many Americans. And audiences warmed to the hotheaded character. O’Connor noted that “there were many, many people out there who thought Archie was 100 percent right about everything,” and surprisingly the show’s most fervent fans lived in homes headed by blue-collar workers. For though Archie is unpleasant and bigoted, he is essentially a decent man, the head of a close-knit family who loves his wife and daughter, tolerates his son-in-law, and struggles with his inability to understand the upheavals in society. As Archie says, “The future is what’s wrong with the world today. There is too much future. There ain’t enough past.”

Archie’s depth and dimension were due in large part to O’Connor’s affecting performance. He humanized the man, slowly revealing a wounded soul who struggles with his fears and whom audiences could hate, pity, and maybe even like, all at the same time. Because of this, Archie—who claims in one episode, “I ain’t no bigot. I’m the first guy to say, ‘It ain’t your fault that youse are colored’”—made white viewers confront their own prejudices. As word spread, viewership grew, and before CBS’ Robert Wood aired the show in summer reruns, it topped Nielsen’s weekly ratings. In the fall, Wood moved All in the Family to its coveted 8 p.m. slot as the lead-in to its Saturday lineup. It continued to rule the Nielsen charts, and during that season at least half of those watching television at 8 p.m. had the show on.

Lear and Yorkin capitalized on their success. They issued an All in the Family record, sold T-shirts, beer mugs, and the books The Wit and Wisdom of Archie Bunker and Edith Bunker’s All in the Family Cookbook, with recipes for quick-drop biscuits and orange barbecued chicken. In March 1972, columnist William S. White noted that politicians discussed “the Archie Bunker vote.” Then four months later at the Democratic National Convention in Miami, Archie received a delegate’s vote for Vice President. In September, he even graced the cover of TIME magazine, with the headline THE NEW TV SEASON: TOPPLING OLD TABOOS.

And though Archie is the blustering and blubbering head of the household, his passions and peeves could not break the bonds of his family, thanks largely to Edith. Despite the show’s radical departure from the norms seen on TV, Edith serves as a direct descendant of a generation of happy homemakers, from June Cleaver on Leave It to Beaver to Margaret Williams on The Danny Thomas Show. Like them, Edith believes she is there to cater to others, and Stapleton imbued her with high energy as a way to demonstrate her desire to please. “The fact that we were in New York, where I knew everybody hurried, and the abusive demands on Bunker’s part pushed Edith into a run,” she recalled of one of her character’s signature traits. And Stapleton borrowed Edith’s high-pitched nasal voice from her portrayal of Sister Miller in Damn Yankees, saying that she added it “for comic purposes.”

Archie might disparagingly call Edith, “a pip,” but Hauser Street’s better angel often displays an unexpected insightfulness that grates on Archie. Behind her ditsy facade lie a bottomless well of tolerance and an innate and noble sense of fairness. O’Connor noted that Stapleton created a “very comical and emotionally very moving,” character, “a benign, compassionate presence” who made “my egregious churl bearable.” As a homemaker, Edith also represents many women in the post Cleaver-Williams era, who nervously found themselves on the edges of the women’s movement, as the show’s second season coincided with the U.S. Senate passage of the Equal Rights Amendment. In the fourth season, the nascent feminist Edith gets a job at the Sunshine Home, a home for the aged. When asked if her character would support the E.R.A., Stapleton responded, “Of course . . . because it is a matter of simple justice—and Edith is the soul of justice.”

You couldn’t help but love Edith, and Mike from the start refers to his mother-in-law as Ma. While Edith was the Hauser Street peacemaker, she usually could not defuse the cringingly contentious arguments between Mike and Archie. Their battles added the perfect combustible fission to the Bunker nuclear family. Archie’s “Polack pinko” son-in-law represents the antiwar counterculture that Archie, who served in World War II, abhors. (It is not surprising watching the show to realize that Lear is obsessed with George Bernard Shaw’s play Major Barbara, with its juxtaposing of liberal and conservative stands.) As Rob Reiner, who played Mike, noted, Lear’s “vision was to get people thinking and talking about the issues of the day. And by using those two characters, Archie and Mike going at each other, it would foster a lot of conversation around the country, which it did.”

Gloria, the Bunkers’ only child, serves as a link between the Greatest Generation of Archie and Edith and Mike’s counterculture generation. She is a good-hearted daddy’s girl raised to be a subservient wife out of the 1950s. Yet Gloria soon embraces the women’s movement, starts to work at a department store, and rebels against the constraints of home in a way that her mother never could. And the onscreen evolution of Gloria reveals that even flaming progressives like Mike are not as open-minded as they claim, as when his own male chauvinist take on the world reveals his innate discomfort with the equality of the sexes.