Few television shows have managed to blend laughter, discomfort, and social commentary as brilliantly—or as dangerously—as All in the Family. When it premiered in 1971, it wasn’t just another sitcom; it was a cultural earthquake. The show used humor as both a mirror and a weapon, forcing America to confront its deepest prejudices through the eyes of a man named Archie Bunker.

But as the series evolved, it raised a powerful question that still lingers today: How far can satire go before it stops enlightening and starts offending?

Let’s explore how All in the Family redefined the boundaries of satire—and why those boundaries still matter.

The Birth of a Controversial Classic

Before All in the Family, sitcoms were polite and predictable. Families were picture-perfect, problems were mild, and jokes were safe. Then came Norman Lear’s vision—a show that would put real social tensions on the screen and make people laugh while squirming in their seats.

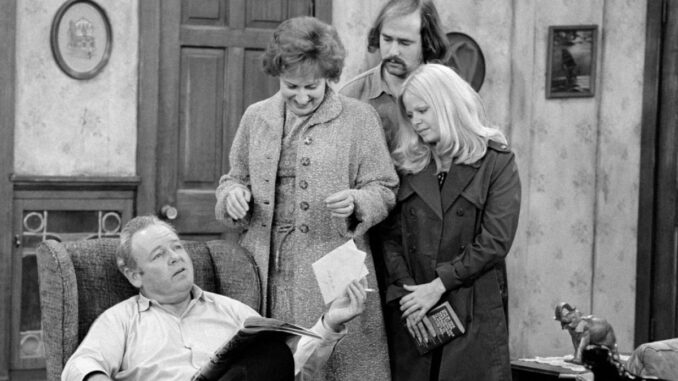

Archie Bunker, the outspoken, blue-collar patriarch, was the centerpiece of this social experiment. He said the things many thought but never dared to voice. Racist, sexist, and stubbornly old-fashioned, Archie became both a caricature and a reflection of an uncomfortable truth: prejudice lived next door, sometimes in our own homes.

Archie Bunker: America’s Most Misunderstood Satire

Archie was meant to be mocked—a walking embodiment of ignorance. But satire can be tricky. Some viewers laughed with him, not at him. They saw Archie as a hero defending “common sense” against changing times.

That’s the paradox of satire: it works best when audiences recognize the exaggeration. But what happens when people don’t see the joke? All in the Family walked that fine line, balancing humor and hate, laughter and learning.

Edith Bunker: The Heart of Compassion Amid the Chaos

Archie’s wife, Edith (played by Jean Stapleton), grounded the series in warmth and empathy. While Archie represented resistance to change, Edith symbolized acceptance and love. Her kindness softened the show’s harshest edges, reminding viewers that humanity still existed amid the noise.

Without Edith, All in the Family might have been too bitter to bear. Her presence gave the satire balance—and soul.

When Satire Meets Reality

The show’s success was undeniable, but so was its controversy. Audiences debated whether All in the Family challenged bigotry or inadvertently encouraged it. Did the laughter expose ignorance—or excuse it?

Satire only works when its message is clear. But in a divided America, clarity was hard to come by. Some viewers saw Archie as a fool, while others saw him as a truth-teller. That split in perception revealed both the brilliance and danger of Lear’s creation.

The Power and Peril of Making People Laugh at Prejudice

Satire relies on irony—on exaggerating flaws until their absurdity becomes obvious. But with All in the Family, that exaggeration hit too close to home. Archie’s bigotry wasn’t cartoonish; it was painfully real.

And that’s where the limits of satire began to show. Could a show mock hate without giving it oxygen? Could it ridicule racism without normalizing it? Lear believed it could, but even he admitted the challenge: “Archie was supposed to be a warning. But some people took him as an endorsement.”

Breaking Television Taboos

Despite (or perhaps because of) the controversy, All in the Family broke more barriers than any sitcom before or since. It openly discussed:

-

Racism and civil rights

-

The Vietnam War

-

Women’s liberation

-

Homosexuality

-

Religion and atheism

-

Economic inequality

These were subjects television simply didn’t touch in the early ’70s. By wrapping them in humor, Lear smuggled social critique into America’s living rooms.

But satire, by nature, risks backlash. All in the Family constantly danced on that knife’s edge.

The Audience Divide: Laughter or Agreement?

What made the show revolutionary also made it dangerous. The writers used humor to expose ignorance, but humor is subjective. One person’s satire is another person’s validation.

When Archie mocked minorities or liberals, progressive viewers saw the irony. Conservative viewers sometimes saw a kindred spirit. Lear’s bold social experiment exposed not just prejudice—but how differently people interpret it.

Michael “Meathead” Stivic: The Liberal Counterweight

Archie’s son-in-law, Michael (played by Rob Reiner), was the voice of the younger, idealistic generation. His endless debates with Archie captured America’s generational clash.

Michael wasn’t perfect either—self-righteous, sarcastic, and stubborn in his own way. Their verbal battles reflected the broader national conversation between tradition and progress. The satire worked because it showed both sides as flawed—but human.

Norman Lear’s Masterstroke—and Dilemma

Norman Lear’s genius was his refusal to pick sides. He let the audience decide. That openness was revolutionary—but also risky. By giving viewers freedom to interpret, he handed them power over the message itself.

Lear later admitted he was stunned by how many fans admired Archie unironically. It proved that satire, no matter how clever, can never fully control its audience.

How the Show Redefined Television Satire

Before All in the Family, TV satire was gentle—poking fun at quirks, not systems. Lear’s show flipped that script. It attacked hypocrisy, power, and moral complacency.

Every episode was a battlefield of ideas disguised as a family argument. That format inspired generations of writers and comedians—from The Simpsons to South Park to The Office.

Without All in the Family, we wouldn’t have the bold, biting satire that defines modern TV comedy.

The Limits of Satire in a Divided Culture

Satire thrives on shared understanding. It works best when everyone “gets the joke.” But All in the Family proved what happens when society itself is divided—the laughter splits too.

When irony meets polarization, satire loses its edge. It stops provoking thought and starts reinforcing bias. That’s the dangerous edge All in the Family danced on for nearly a decade.

Was Archie a Mirror or a Mask?

Archie Bunker remains one of TV’s most complex characters. He could be infuriating one moment and oddly sympathetic the next. That duality made him real—but also controversial.

Some argued that the show’s humor let viewers hide behind laughter, avoiding the deeper issues it exposed. Others believed it opened doors for honest conversations America desperately needed. Both are true—and that’s what makes the satire so enduring.

The Evolution of Satire Since the 1970s

Today’s comedies owe a debt to All in the Family. Shows like Family Guy, Modern Family, and Black-ish continue to use humor to explore social themes. But they’ve also learned from Lear’s cautionary tale: satire must evolve with its audience.

Modern satire tends to clarify its stance more directly, ensuring viewers don’t mistake the joke for endorsement. In that sense, All in the Family walked so others could run.

Why the Show Still Matters Today

In a world where outrage spreads faster than understanding, All in the Family feels more relevant than ever. It reminds us that satire can educate—but it can also divide.

Its legacy challenges creators and audiences alike to think critically about how humor shapes perception. Are we laughing to learn—or laughing to ignore?

That question still defines the limits of satire today.

Cultural Impact That Still Echoes

Half a century later, the show’s fingerprints are everywhere. It taught television to be brave—to speak the unspeakable and find truth in discomfort. It showed that laughter could be a catalyst for change, even when it made people uneasy.

That’s the true power of satire when done right: it doesn’t just entertain—it provokes reflection.

Conclusion: Where Humor Meets Humanity

All in the Family was never just a comedy. It was a social experiment wrapped in laughter, daring to ask how much truth audiences could handle. It revealed both the brilliance and fragility of satire: its ability to enlighten, but also to be misunderstood.

In the end, Archie Bunker wasn’t a villain or a hero—he was a lesson. A reminder that laughter is powerful, but only when we listen to what it’s really saying.