When Lear and Bud Yorkin pitched the series to CBS, the network was eager for a shift away from its traditional offerings, but not quite prepared for the bold move that All in the Family represented. Just a week before its January 12, 1971 debut, CBS was criticized for failing to address the pressing social issues of the time, as noted in a Variety report highlighting the network’s struggle to attract a more socially conscious audience.

The country was rife with unrest, from the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy to the protests against the Vietnam War. Yet, the top-rated shows of the late 1960s presented a narrow view of life, focusing on idyllic family values and escapism.

Network executives might have wanted to embrace relevant content, but the advertising-driven television landscape was resistant to anything deemed too radical. Examples of this include the backlash against Petula Clark’s duet with Harry Belafonte, where a sponsor demanded a moment of racial intimacy be cut, and the cancellation of The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour for its politically charged content.

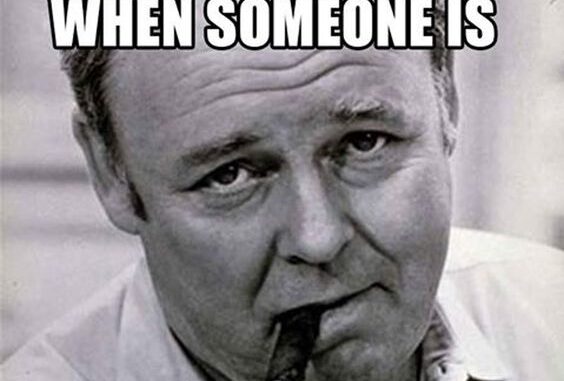

Despite these challenges, CBS ultimately supported All in the Family, with network president Robert Wood acknowledging the need to align with contemporary life. The show featured elements that connected it more closely to reality, such as a flushing toilet sound—a first in television—that signaled the Bunkers lived in a world much like the audience’s own.

The incorporation of a television set in the Bunkers’ living room further underscored this connection, as it mirrored the way most American families arranged their homes around their TVs. These small yet significant details made viewers feel seen and heard, which contributed to the show’s massive success. All in the Family was embraced by audiences precisely because it reflected the complexities and struggles of real life, making it a revolutionary force in television history.