Later this month, the beloved 1990s family sitcom “Roseanne” returns to ABC. The reboot comes at a perfect cultural moment–television comedy is thriving in its second Golden Age, and while recent shows have made strides exploring issues of identity from race to sexuality, the elephant in America’s living rooms, class, has been only spottily addressed in the 20 years that “Roseanne” has been off the air.

From their post-WWII inception, American sitcoms showcased primarily affluent, aspirational, white families; think of the Cleavers on “Leave it to Beaver,” the Andersons on “Father Knows Best,” and the Nelsons on “The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet.” An academic study of 262 situational comedies from 1946-1990 revealed that only 11 percent of programs featured blue-collar characters as heads of household – the most notable were the two “ethnic” comedies that came directly from old radio programs like “The Goldbergs” and “Amos ‘n’ Andy.” In the 1950s and 1960s, the genre was dominated by professional, college-educated protagonists and their impressive, pristine homes. (The only real exception was “The Honeymooners,” which aired in the mid-50s and starred Jackie Gleason as New York City bus driver and would-be domestic batterer Ralph Kramden.)

Everything changed in the 1970s, when the media “discovered” the American working class, as the country confronted a host of economic changes alongside social shifts stemming from the civil rights and women’s liberation movements. The prosperity of the postwar era gave way to a period of instability marked by sluggish growth, record inflation, high oil prices, deindustrialization and foreign competition. While communities of color had always struggled to get by due to fewer opportunities for living wage work, many white Americans found that their share of the postwar bounty was shrinking during this period, threatening their standard of living for the first time since the Great Depression.

Although the stubborn myth of America as a “classless” society persisted, our socioeconomic reality more closely resembled the class stratification that had been present for generations in Europe. Fittingly, our first class-conscious, post-corporate hit sitcom was based on a program from across the pond. Inspired by Britain’s “Till Death Do Us Part,” writer and producer Norman Lear created “All in the Family” in 1971, which ran for nine seasons on CBS. Like its British inspiration, the show was about the generation gap between a reactionary patriarch and his more liberal offspring.

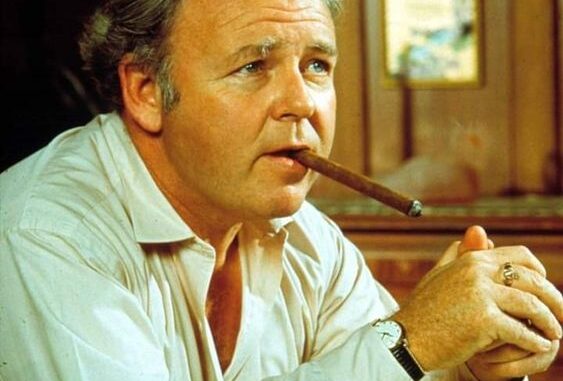

“All in the Family” was a groundbreaking commercial success, ranking number one in the Neilsen ratings for five years. By 1975, one-fifth of the entire country was tuning in. The propelling force of “All in the Family” was Carroll O’Connor as Archie Bunker, a warehouse dock worker who drove a taxi for extra income and lorded over his family in their Queens row house. The sitcom, like the rest of Lear’s oeuvre, represented a turning point for its engagement with topical, controversial themes, such as race relations, homosexuality and feminism – an effort to reach baby boomer audiences – and for representing the kind of ordinary, working people who had thus far been invisible on screen. Archie was one of television comedy’s first white hourly wage earners, undermining the media perception that white Americans made up a homogeneously middle-class demographic.

“Archie chomps cheap cigars, swills supermarket beer and controls all foreign and domestic rights to his favorite chair in front of the battered TV,” read a 1971 Newsweek review. Viewers could see reflections of their own homes in the Bunker’s “cheery-drab” row house, complete with chipped wallpaper, fingerprints on the light switches, and grime on the kitchen tiles. According to Ryan Lintelman, curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, “The living room set of the Bunker home, like its location in Astoria, Queens, was designed to emphasize Archie’s working-class bona fides.” His iconic armchair, now part of the museum’s collection, “was supposed to look like a well-used piece of furniture that could have been in any family home: comfortable but worn, somewhat dingy, and old-fashioned.” (Earlier this year, the family of Jean Stapleton, who played Archie’s wife Edith, donated the apron she donned and other artifacts from her career to the museum.)

The dilapidated aesthetic mirrored Archie’s character traits; he was retrograde, incapable of dealing with the modern world, a simpleton left behind by the social upheavals of the 1960s and 1970s, a pathetically displaced “historical loser.” Lear used him as a device to make racism and sexism look foolish and unhip, but liberals protested that as a “loveable bigot,” Archie actually made intolerance acceptable. Lear had intended to create a satirical and exaggerated figure, what one TV critic called “hardhat hyperbole,” but not everyone got the joke.

Archie was relatable to audience members who felt stuck in dead end jobs with little hope of upward mobility, and who were similarly bewildered by the new rules of political correctness. To these white conservative viewers, he represented something of a folk hero. They purchased “Archie for President” memorabilia unironically and sympathized with his longing for the good old days. Archie was both the emotional center of “All in the Family” and the clear target of its ridicule.

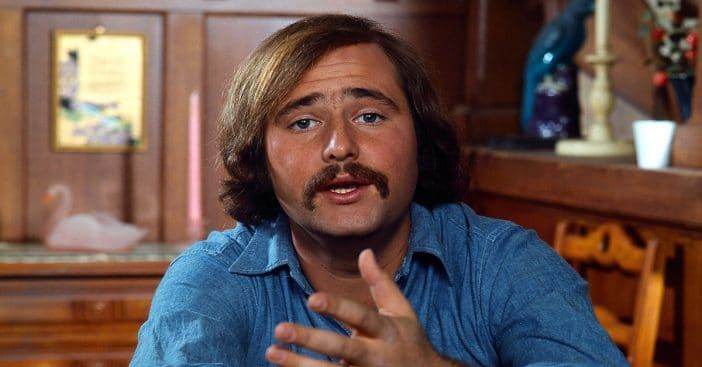

“All in the Family” opened the floodgates for more representations of the working poor in 1970s situation comedies. “Sanford and Son,” also produced by Lear, was about the urban African-American underclass, and took place in a literal junkyard in Los Angeles. Comedian Redd Foxx played Fred Sanford, a grumpy and intolerant schemer (the “trickster” archetype from black folklore) who refused to adhere to the middle-class social mores that his son, Lamont, aspired to.

In a sense, Fred was the black equivalent to Archie, and the show was another take on the decade’s cultural generation gap. “Good Times” featured a hardworking black family living in the inner-city projects of Chicago, and addressed realistic problems like eviction, street gangs, racial bias and an inadequate public school system. Several black activists faulted “Good Times” for relying on harmful stereotypes and buffoonery. Lear said recently on a podcast that members of the Black Panther Party specifically challenged him to expand the range of black characters on his shows. But others appreciated the show for portraying an intact black nuclear family – something the actors had insisted upon during the production process. Together, these programs sparked debate about what types of television images were best for the African-American community. This may have ultimately led to the slew of sitcoms about well-to-do black families, like “The Jeffersons,” and later, “The Cosby Show,” and “The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air,” which some critics believed offered more uplifting representations of African Americans.

The second-wave feminist movement of 1970s largely emphasized opportunities for professional women, reflected in the popularity of “The Mary Tyler Moore Show.” But working-class women were not entirely absent from sitcoms; in “Alice,” a widowed mother made ends meet by waitressing in a roadside dinner. Yet even though women and people of color have always made up the majority of our country’s low-income workers, it was Archie Bunker who remained the face of blue collar America in the popular imagination for decades.

Finally, in 1988, “Roseanne” debuted on ABC. The show starred Roseanne Barr and revolved around two working parents raising their children in a fictional Illinois town. It was a breakout smash, tied with “The Cosby Show” as the most popular television program in the country in the 1989-1990 season. In an interview with Terry Gross at the time, Barr emphasized, “It’s a show about class and women.” Her character, Roseanne Conner, worked a series of unstable, thankless pink-collar service jobs. In an article for The New Republic, journalist Barbara Ehrenreich observed that characters like Roseanne made visible the “polyester-clad, overweight occupants of the slow track; fast-food waitresses, factory workers, housewives…the despised, the jilted, the underpaid.” “Roseanne” conveyed a sort of “proletarian feminism” in which a mother and wife could express maternal resentment, take up excess physical space, and behave in unladylike, unruly ways. Economic struggle served as a theme of the series, but the Conners had no aspirations towards upper middle-class culture. Fans of the show praised it for its “realness,” a way of indicating that the characters looked, talked, and labored like them

This realistic take on the average American family – with no shortage of dysfunction – continued into the 1990s, which may have been the heyday of the working-class sitcom. “Grace Under Fire” and “The Nanny” centered working women, and “Married With Children,” as well as “The Simpsons” and “King of the Hill” used lowbrow, sarcastic humor to lampoon normative blue collar masculinity, bringing us a long way from “Father Knows Best.”

Since then, television comedy has moved away from the traditional sitcom format – laugh tracks, especially, are seen as hacky and outdated, and the concept of “family” has evolved to include non-relatives – but class has also taken a backseat to more en vogue identity politics, perhaps because of the slow but steady increase in opportunities for historically underrepresented groups in Hollywood to tell their own stories.

But with growing income inequality and labor strikes back in the news again, it feels like the right time to revisit class. Of course, ’90s nostalgia may be enough for the “Roseanne” reboot to coast on, particularly for millennial audiences – but rumor has it that this season will also feature both gender fluid characters and Trump supporters. The same question that plagued “All in the Family” will likely be posed again; who will viewers identify with, and who will they laugh at? Class politics on sitcoms has always been more complicated than we give the genre credit for.