The news lands with a soft thud, not unlike a freshly fallen snowflake in a vast Montana field, yet it reverberates like a distant thunderclap. Taylor Sheridan, the architect, the maestro, the singular, uncompromising voice behind the Yellowstone universe, is reportedly handing off showrunner duties on the newest spinoff. And I, like many devotees of the Dutton saga, am worried.

It's a worry born of respect, an apprehension that stems from the profound influence Sheridan has exerted over the most compelling contemporary Western narrative. He isn't just a writer; he's a brand. He’s the dusty boots on the ground, the whiskey-soaked philosopher by the campfire, the unsparing eye that sees the brutal beauty and moral ambiguity of the American frontier, past and present. From the sharp-edged dialogue that crackles like dry kindling to the vast, breathtaking cinematography that makes the landscape a character in itself, every frame, every spoken word, every violent consequence in the Yellowstone saga bears his unmistakable imprimatur.

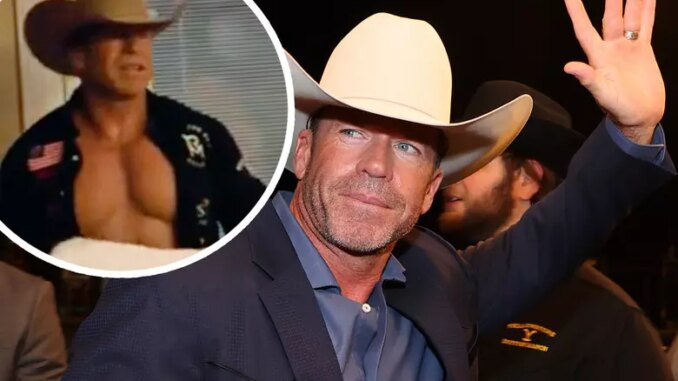

Think of the sheer authenticity he brings. Sheridan doesn't just write about cowboys; he is one. He lives the life, breathes the dust, understands the unspoken codes of the ranch. This isn't a writer crafting a fantasy from a city office; it's a storyteller translating a lived experience, albeit embellished, onto the screen. It's why his characters feel so deeply etched, why their struggles resonate with a raw, undeniable truth. Whether it's the stoic resolve of James Dutton in 1883, the hardened pragmatism of Jacob in 1923, or the simmering fury and reluctant wisdom of John Dutton III, their souls are forged in the fires of Sheridan's singular vision.

This worry isn't about a lack of faith in the concept of a new spinoff. The Yellowstone universe is rich, fertile ground, brimming with untold stories of sprawling landscapes and desperate people. It's about the fear of dilution, of that unique, bracingly authentic flavor being watered down when the master chef steps away from the kitchen.

Consider the craft. Sheridan’s narratives are not just plots; they are intricate tapestries woven with threads of history, family loyalty, environmentalism, political intrigue, and the ever-present threat of violence. He understands that the land is not just a backdrop but a character, dictating destinies and shaping souls. He isn't afraid to let his characters be morally compromised, to grapple with choices that leave no one entirely clean. This moral ambiguity is a hallmark of his work, separating it from more conventional, black-and-white Westerns.

What happens when another showrunner takes the reins? Will the dialogue still possess that sharp, poetic rhythm, or will it become merely functional? Will the pacing still allow for moments of quiet contemplation amidst the chaos, or will it be rushed by the demands of a focus-grouped audience? Will the camera still linger on the stark, unforgiving beauty of the landscape, allowing it to breathe and speak, or will it simply be another pretty shot?

The danger lies in the loss of that indefinable it factor. That gut feeling, that intuitive understanding of the world he’s built. It’s the difference between a meticulously crafted, custom-fit saddle and a mass-produced one; both might serve the purpose, but only one truly feels like an extension of the rider.

Of course, one could argue that Sheridan’s empire has grown too vast, that he’s spread himself too thin across Yellowstone, 1883, 1923, Mayor of Kingstown, Tulsa King, Lawmen: Bass Reeves, and others. Perhaps handing off duties is a necessary step to maintain quality, to prevent burnout. And certainly, there are immensely talented showrunners in Hollywood who could breathe life into a new corner of this world.

But this isn't merely about competence; it's about congruence. It’s about maintaining the singular voice that has elevated these stories from mere television shows to cultural phenomena. It’s about protecting the integrity of a universe that, under Sheridan’s guidance, feels less like fiction and more like an alternate reality we're allowed to glimpse.

My worry, then, is not an indictment of any future showrunner, nor a dismissal of the potential of a new story. It is a genuine concern for the soul of the Yellowstone saga. It's the fear that the sharp edges might soften, the grit might polish, and the uncompromising vision might become, by necessity, compromised. It's the trepidation that the unique, vital pulse of Sheridan's world might slow, diminishing into something merely good, when we've become accustomed to greatness. It's the hope, against a nagging doubt, that the new blood can honor the old, and that the Dutton legacy will continue to thunder across our screens, unbowed and untamed, even without the master's direct hand on the reins.