Given how often I complain about the so-called “Bridgerton effect” — that pop sanitization of period dramas, where everything turns into string-quartet pop covers, Instagram-ready costumes, and conflicts without real consequences — it would be perfectly logical for me to hate the series that dominated streaming during the pandemic. And yet, here we are. A fourth season, feeling like a fifth if we count Queen Charlotte (my favorite), and the uncomfortable but honest realization: even clichéd, kitschy, and unapologetically melodramatic, Bridgerton remains a delight. And worse — or better — deservedly so.

The fourth season, based on An Offer From a Gentleman by Julia Quinn, arrives after nearly a two-year hiatus with a curiously comforting energy. There is no intention whatsoever of reinventing the wheel. On the contrary, everything here operates in “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” mode. The structure is familiar, the split season is annoying, and the tone remains that of a lavish soap opera in priceless gowns. And still, something feels different. For the first time since the show’s debut, repetition doesn’t read merely as laziness. It reads as choice.

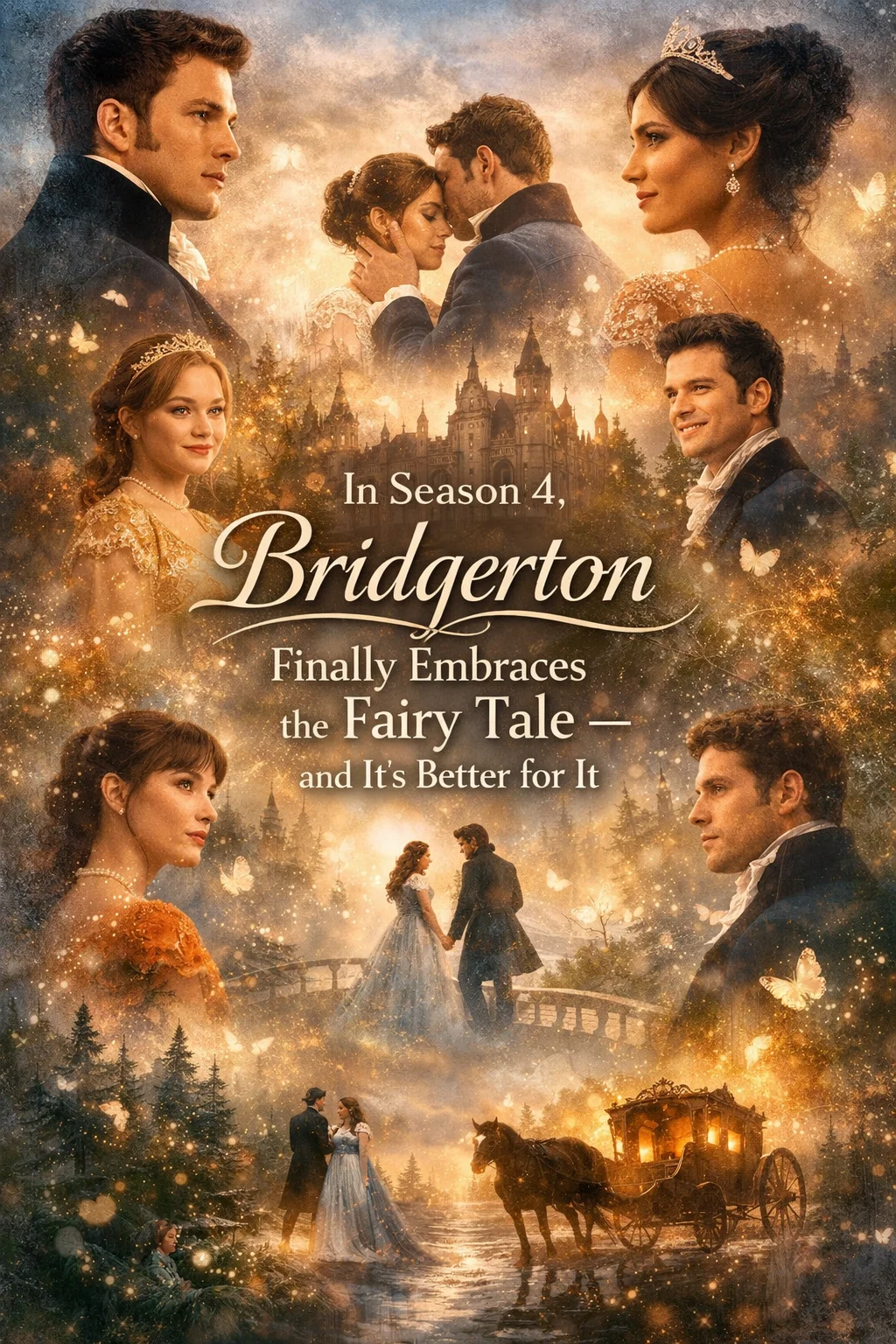

Benedict Bridgerton takes center stage after years of drifting through the narrative as the family’s bohemian wanderer, a character who seemed to exist solely for libertine parties, smoky studios, and vague identity crises. This season abruptly ends his lothario phase and pushes him into a classic romance, perhaps too classic. His story with Sophie Baek is, bluntly, Cinderella. Or, more precisely, A Cinderella Story, early-2000s version, just without Hilary Duff singing “Come Clean.” The masked ball, the magical encounter, the disappearance at midnight, the socially invisible woman who becomes the object of desire: it’s all there, without shame.

That is, simultaneously, the season’s greatest weakness and its greatest strength. Yes, the allegory is painfully literal. Yes, the script sometimes underlines the fairy-tale reference as if afraid the audience might miss it. And yet, it works. It works because Cinderella is a resilient archetype. And because, for the first time in a long while, Bridgerton recovers something it had abandoned: a real obstacle between its leads.

Sophie is not merely a woman with a secret. She is a maid. She works for an aristocratic family and lives under a regime of economic and social dependence that makes any relationship with a Bridgerton not just unlikely, but forbidden. The romance is no longer driven solely by emotional misunderstandings; it is shaped by class, labor, and hierarchy. Risk returns. Cost returns. There is something at stake again.

That shift reverberates throughout the season. Unlike previous years, in which side plots often sabotaged — or worse, mocked — the central romance, the subplots here finally speak to one another. Varley’s wage dispute with the Featheringtons, Lady Danbury’s historical discomfort in her role as the Queen’s perpetually subordinate “best friend,” the Mondriches’ uncertainty about the price of social ascension, even Eloise’s reflections on what remaining unmarried would mean materially, all orbit the same axis. Power, dependence, consent.

What I do find genuinely problematic is the idea of feeding the illusion that a man — especially one like Benedict — could be “redeemed” or “fixed” by true love. That said, Shonda Rhimes is so brilliant that she almost convinces me it’s possible. Almost. (But no. It isn’t.)

This is Shonda Rhimes 101 finally working as intended. The same mechanism that has sustained Grey’s Anatomy from the start — smaller stories that expand, complicate, and deepen the central arc — at last finds balance in Bridgerton. For the first time, the show understands that world-building is not about excess characters, but about thematic coherence.

That doesn’t solve everything. The romance between Benedict and Sophie, at least in this first half, is a little too well-behaved. There is chemistry, tenderness, and an excellent performance from Yerin Ha, but the spark is missing. The heat that defined Daphne and Simon, Anthony and Kate, even Colin and Penelope at their best, isn’t quite there yet. Ironically, the season reserves its most compelling erotic charge for the supporting characters, and especially for Violet Bridgerton. Ruth Gemmell emerges as the true emotional protagonist of the year, turning mature desire, late-life flirtation, and restrained anticipation into the season’s most vibrant arc.

Still, there is something deeply reassuring about watching Bridgerton finally accept what it is. A romantic fantasy that never was — and perhaps never wanted to be — a rigorous historical reconstruction. A melodrama that prefers excess over restraint, grand gestures over minimalist subtext. When the show tries to be “important,” it usually stumbles. When it embraces pleasure, artifice, and sentimentality, it finds its footing.

Season four also does something that once seemed impossible: it restores density to the show’s universe. By acknowledging that, even in this idealized world, structural inequality persists, Bridgerton brings back a sense of consequence that had gradually dissolved over the years. It’s not a radical critique of the system — far from it — but it’s a step beyond the colorful cynicism that threatened to turn everything into frictionless fantasy.

There are reasons for caution. Bridgerton has a history of unraveling in the back half of its seasons. The promise of yearning must translate into physical tension, emotional risk, and scenes that justify the investment. But for now, everything aligns. The storylines converge, the theme holds, the pleasure remains intact.

In the end, perhaps the greatest irony is this: the series that symbolizes everything I usually criticize in period dramas only works when it stops pretending to be something else. When it embraces cliché. When it leans into kitsch. When it understands that sometimes a well-told fairy tale is exactly what the audience wants.

And I, against all expectations, still want it too.