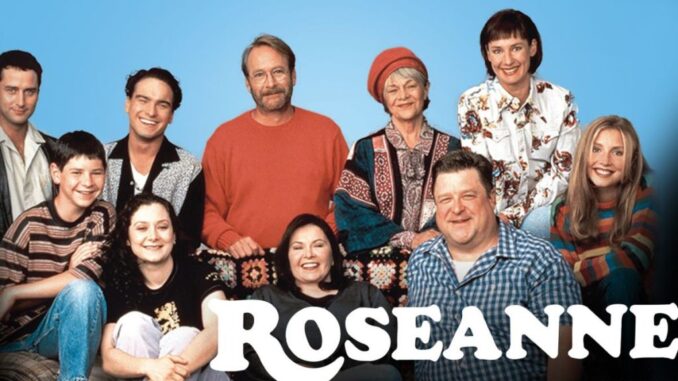

In TV show ‘Roseanne’ and its reboot, a comedy that actually cares about working class America

The American show continues to situate its characters’ life experiences within a wider social and economic context.

Roseanne’s audience numbers are even more striking when they are divided along geographical lines. The premiere failed to break into the top 20 shows in New York or the top 30 in Los Angeles – America’s two biggest markets – but it topped the ratings in many of the fly-over states of middle America. Since then, Roseanne has continued to dominate its timeslot.

In terms of genre, Roseanne is what Horace Newcomb in his seminal TV: The Most Popular Art defined as a domestic comedy. In contrast to situation comedies that tend to focus on physical comedy and farcical situations – like Seinfeld (1989-1998) and 30 Rock (2006-2013) – domestic comedies focus on family life and interpersonal problems that are ultimately resolved through talking.

What has always been most interesting about Roseanne, and the source of its enduring appeal, is how its portrait of working-class America both taps into contemporary cultural anxieties and subverts the traditional moral and aesthetic standards of domestic comedy.

Originally, domestic comedy was a middle-class genre. It emerged in the 1950s as television became a dominant medium. Early exemplars including Father Knows Best (1954-1960), Leave it to Beaver (1957-1963) and The Donna Reed Show (1958-1963) were explicitly targeted towards the rapidly expanding American middle class. They served up moral tales, and an idealised version of the middle-class family that became a template for the genre well into the 1980s.

Roseanne (1988-1997) was different. Roseanne (Roseanne Barr) and Dan Conner (John Goodman) were working-class parents, precariously employed and always struggling to make ends meet. They were acutely aware of the gap between their daily grind and the promise of the American dream. This self-awareness and sense of fatalism about their ability to get ahead gave the show its heart.

Many have theorised about the return of Roseanne in the age of US President Donald Trump. Some have praised it for giving a voice to working-class families. Others, such as writer Roxane Gay, have decried the actor Roseanne Barr’s public support for Trump.

Partisan politics aside, Roseanne has filled a void. The most popular domestic comedies over the last couple of decades, such as Everybody Loves Raymond (1996-2005) and Modern Family (2009-), illustrate an ongoing lack of reflection within the genre upon wider economic realities. These shows normalise images of middle-class comfort, making them appear to be reflective of wider America.

Modern domestic comedies are often socially progressive but economically tone deaf. Roseanne, with its relentless focus on financial hardship, is in many ways a response to these recent representations of American family life.

The networks that produced domestic comedies in the 1950s saw themselves as helping to foster a unified American way of life that would diminish geographic, ethnic and especially class differences within American society. The president of NBC – the network that aired Father Knows Best – epitomised this vision in his insistence that “characters will serve to illuminate the problems of our times and our fundamental beliefs”. These shows, he maintained, will detail “the art of living itself”.

These early domestic comedies celebrated the nuclear family – all white, middle class, with professional fathers and stay-at-home mothers – and the simple pleasures of home life. Fathers worried that they were spending too much time at home at the expense of furthering their careers. Mothers would meet independent women that led them to question their lives as homemakers.

Storylines that dealt with the children typically provided an opportunity for lessons on middle-class morality. Problems came from temporary lapses in proper behaviour, rather than any institutional or social issues, and were always resolved with family values.

This worldview was also evident in the few working class shows that made it to television in the middle of the 20th century. In The Life of Riley (1953-1958) and The Honeymooners (1955-56) the chaotic scheming of Chester Riley and Ralph Kramden served as a counterfoil to the ordered lives of the middle class families on television. Both men were working class caricatures: narrow minded, impulsive and constantly drawn to get-rich-quick.