Exploring the Queer Subtext and Representation in Fannie Flagg’s Southern Classic

A Story of Friendship—or a Love Story in Disguise?

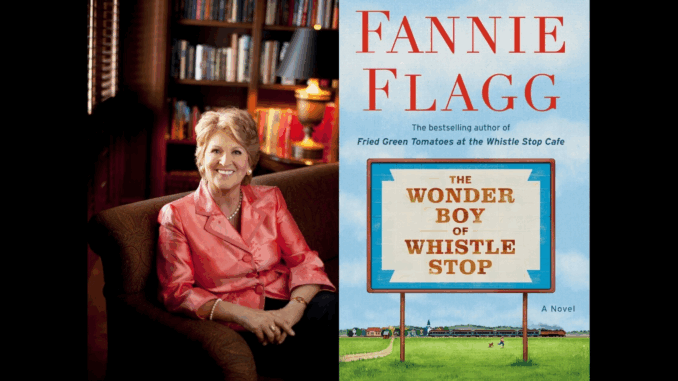

Fannie Flagg’s Fried Green Tomatoes at the Whistle Stop Cafe, published in 1987, has captivated readers for decades with its rich Southern storytelling, deeply drawn characters, and interwoven timelines. But for many readers, one question has persisted: Is this an LGBTQ+ novel?

At its heart lies the relationship between two women—Idgie Threadgoode and Ruth Jamison—whose bond spans years and endures hardship, heartbreak, and societal pressures. The nature of their connection has inspired both scholarly debate and emotional resonance within the LGBTQ+ community. Is theirs a deep platonic friendship? Or is it a coded lesbian relationship that had to be hidden due to the time it was written and the era it depicted?

The answer is layered and reflective of both historical constraints and literary subtlety. Let’s explore how Fried Green Tomatoes functions as a queer narrative, what the novel says—and doesn’t say—about Idgie and Ruth’s relationship, and how it fits into the broader context of LGBTQ+ literature.

The Novel: Subtle Yet Unmistakable Queerness

Ruth and Idgie: Not Just Friends?

In Fannie Flagg’s novel, Idgie Threadgoode is portrayed as a fiercely independent, tomboyish woman who refuses to conform to societal expectations. She wears men’s clothes, drinks, gambles, tells tall tales, and openly defies traditional gender roles. From an early age, she is shown to have a special affection for Ruth Jamison—a soft-spoken, religious young woman who initially resists Idgie’s chaotic charm but eventually becomes her lifelong partner in running the Whistle Stop Café.

Throughout the book, Flagg never explicitly labels their relationship. There are no sexual scenes. No one calls them lovers. But there are intimate emotional declarations, domestic partnership dynamics, and the simple fact that they raise a child together. Idgie and Ruth live as a couple in every way that matters. The novel describes them raising Ruth’s son, Buddy Jr., and building a life together.

One of the clearest literary clues comes when Ruth leaves her abusive husband and moves in with Idgie. In letters and dialogue, their love is tender, deeply affectionate, and unwavering. Even without explicit language, the queer subtext is strong—and, for many, unmistakable.

Authorial Intent: Fannie Flagg’s Queer Perspective

Fannie Flagg herself is a lesbian, though she has lived much of her life privately and has rarely spoken publicly about her sexuality. However, her understanding of Southern culture and the need for subtlety in queer storytelling during the 1980s is evident in her writing.

In interviews, Flagg has acknowledged that many readers interpreted Idgie and Ruth as a romantic couple, and she has welcomed that reading, though she stops short of confirming it outright. In this way, the novel becomes a coded love story, reflective of both the era it was published in and the 1920s–1940s setting of the narrative.

The Film: A Softer, Sanitized Version?

The 1991 Adaptation and Hollywood Constraints

When Fried Green Tomatoes was adapted into a film in 1991, the central relationship between Idgie and Ruth was significantly toned down. While the film preserves their deep emotional bond, it removes or dilutes many of the more explicitly romantic cues found in the novel.

Director Jon Avnet has said that the relationship was meant to be open to interpretation, and that the goal was to portray a love story without alienating mainstream audiences in an era when overt lesbian representation was still rare in Hollywood.

This ambiguity caused frustration in LGBTQ+ circles at the time. Many critics and viewers felt that Hollywood had “straight-washed” a clearly lesbian relationship for broader acceptance. One particularly emotional scene from the novel—a kiss between Ruth and Idgie—is left out of the film entirely.

Despite that, many LGBTQ+ viewers still recognized themselves in the film’s portrayal. The chemistry between Mary Stuart Masterson (Idgie) and Mary-Louise Parker (Ruth), their domestic partnership, and the narrative choices all point toward a love story, even if it isn’t overtly named as such.

Queer Coding and Southern Gothic Tradition

Fried Green Tomatoes fits within a long literary tradition of queer-coded Southern fiction, particularly Southern Gothic works. Much like Carson McCullers’ The Member of the Wedding or Tennessee Williams’ plays, Flagg’s novel uses nonconformity, eccentricity, and emotional intensity to signal queerness without direct labels.

Idgie, with her boyish clothes and refusal to marry, is clearly positioned as queer-coded. Ruth, although more traditional, finds her greatest happiness away from the expectations of marriage and in the quiet intimacy of life with Idgie.

This literary style allowed authors to explore LGBTQ+ themes during times when censorship and cultural taboos made open depictions risky or impossible. As such, Fried Green Tomatoes is part of a subversive canon of queer literature, where identity is revealed through metaphor, relationships, and community rather than labels.

A Story That Resonates with LGBTQ+ Readers

A Queer Love Without the Tragedy

One of the reasons Fried Green Tomatoes resonates so deeply with queer readers is that—unlike many LGBTQ+ stories of the time—it is not a story of shame, punishment, or complete erasure.

While the characters face hardship, their relationship is never vilified. There is no climactic “outing,” no homophobic violence, no punishment for living unconventionally. Instead, Ruth and Idgie are loved by their community, respected as partners, and allowed to grow old together in peace.

This representation, especially in the late 1980s, was rare and radical. Even without overtly naming their love, the book gives readers a model of queer joy and domestic life, where love endures beyond fear.

A Queer Legacy, Quietly Built

Today, Fried Green Tomatoes at the Whistle Stop Cafe is widely regarded as a queer classic, even if it has flown under the radar of more explicitly LGBTQ+ literary discussions. It’s been embraced by lesbian book clubs, analyzed in academic queer theory classes, and referenced in pop culture as an example of “the love that dares not speak its name.”

In recent years, there have been increasing calls for more explicit LGBTQ+ adaptations of beloved stories like Fried Green Tomatoes. Some readers hope that, one day, a new version might present Idgie and Ruth’s love without subtext—openly, proudly, and canonically queer.

Conclusion: Queer in Spirit, If Not in Name

So—Is Fried Green Tomatoes an LGBTQ+ novel?

The answer is both yes and intentionally ambiguous.

Fannie Flagg’s novel may not use the word “lesbian” or describe Idgie and Ruth as romantic partners in literal terms. But through its storytelling, its characters, and its emotional truths, it gives us a deeply queer narrative—one of love, resistance, chosen family, and emotional freedom.

For readers in the LGBTQ+ community, it offers not just representation, but hope. And for all readers, it challenges the notion that love must look one way or be named to be real.

In the end, Fried Green Tomatoes tells us what matters most: that love—no matter how it’s expressed—deserves to be seen, remembered, and celebrated.