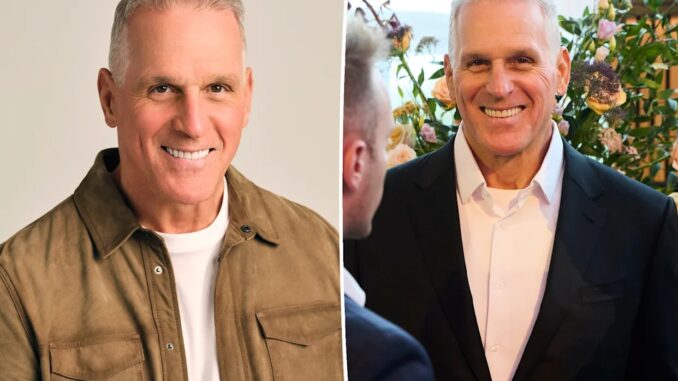

The new Golden Bachelor, Mel Owens, openly stated that he only wanted to date younger women. Was he in the wrong?

The Golden Bachelor is part of the ABC reality TV show franchise that features a single man who dates multiple women over a few weeks in search of finding love and perhaps a spouse. Even before the second season even aired, it created a huge controversy.

Mel Owens, the new Golden Bachelor, casually announced on a podcast that he’s only open to dating women 45 to 60 years old. Owens is 66.

This did not go over well on social media, with many women calling him sexist and ageist, among other choice words. And it’s no surprise that many of the 23 women aged 58 to 77 vying for his affection on the show called him out in the first episode, which aired on September 24. And he was dutifully roasted by the women who hadn’t been eliminated in the third episode.

Owens, a former NFL player-turned-lawyer and the divorced father of two young men, said he was sorry. “I sincerely apologize. It was insensitive, unfair,” he said. “It’s truly a privilege for me to be The Golden Bachelor, and I hope you forgive me and let me earn it back. Age is really just a number, and spirit has no age.”

Still, his initial comment and “my bad” response when called out raises questions. Many of us question or dismiss age-gap relationships. Is age just one romantic preference among many, or something else entirely? Is it also wrong to refuse to date a smoker, gambler, or addict, or reject someone taller or shorter, or a single parent or someone who’s never been married? Was Owens being ageist or are there practical reasons for desiring a younger romantic partner as we age (or at any time)? And is age truly just a number—or is it a meaningful indicator of other factors, like health and maturity?

Social scientists have explored and attempted to answer those questions. Their work could help us to understand ourselves just a little better—and the research helps unearth a bias we all have, even if we aren’t aware of it: internalized ageism.

Age and marital satisfaction

We know that our search for love becomes a lot more nuanced and intentional as we age. Both men and women tend to be more satisfied with having a younger spouse over an older one, according to a 2018 study. As the researchers write, “Even though women with older husbands start out at lower levels of satisfaction, they also, just like their husbands, experience the steepest decreases in marital satisfaction with marital duration. As a result, women with much older husbands who have been married at least five years are particularly dissatisfied.”

Owens’ former wife of some 17 years is 20 years his junior, so it’s hardly surprising that he would prefer to skew younger as he looks for love again. Research indicates that many formerly married men seek a much-younger partner the second time around. About 20% of men who marry again have a wife who is at least 10 years their junior, while another 18% chose a woman who is six to nine years younger, according to the Pew Research Center.

Although many women gravitate toward a male romantic partner of their own age, a new study finds that women who are more than 10 years older than their male partner tend to be “the most satisfied with and committed to their relationships compared with both women who were younger than their partners, as well as women whose partners were close in age.”

Part of that may be driven by the fact that older divorced or widowed women are not interested in becoming what’s known as a “nurse with a purse”—count 69-year-old TV host Gayle King among them. “I [would] like it that they have all of their teeth,” she says. “That would be nice.” A study of dating later in life led by Cassandra Cotton, a family demographer and sociologist at Arizona State University, found that many women were rightly concerned about a potential new partner’s health and the possibility of becoming responsible for caregiving again after raising children or tending to ailing husbands or parents.

This is why many women in their 60s and older prefer a “live apart together” (LAT) relationship over cohabiting with a male romantic partner, according to an article in Canada’s Globe and Mail. “I don’t want to take care of anybody. I want to take care of me,” says a woman in her late 70s who has been divorced twice. “You want to be friends and get together, when I say it’s OK to get together? Fine. But to be in a relationship where I have to answer to somebody else? Been there, done that, don’t want to do it again.”

Cotton’s results were similar to what social scientist Lauren E. Harris found in her study of singles aged 60 to 83.

“Older single women were quite aware of the ways men may require their time, attention, and care. Though they were looking for romantic relationships and companions, women prioritized performing less carework over a relationship that required carework like raising a man’s children or nursing him through decline,” Harris wrote.

Being with a younger partner or one around their age might help them avoid that, although there are no guarantees that they won’t become ill, disabled, or meet an early demise.

Are age preferences discriminatory?

Are older women “wrong” for wanting to avoid that kind of caregiving? Are they being ageist? Should we apply a different standard for men?

It’s all too easy for an older woman to slip into the role of “purse.” A study of nearly 4,000 baby-boomer widows, most of whom were widowed in their 50s, found that many were inexperienced around money issues after the death of their husband, making them easy prey when repartnering. The widows who were financially savvy were less likely to be taken advantage of.

There’s another thing working against women when it comes to finding love later in life—family caregiving responsibilities. According to Harris’ study, men often considered single women in their age group less desirable if they are deeply involved in caring for their adult children, their grandchildren, or both. Some didn’t want to be with a woman who wouldn’t make him her top priority and thus looked for a romantic partner who “would put them first and stop mothering their grown children.”

The women, however, considered men in their age group who were close with their families to be more desirable because it made them seem stable, committed, and family-oriented.

Practical matters aside, there might be something else going on that is often overlooked when we make romantic decisions—internalized ageism, a type of implicit ageism that not only is harmful to envisioning our future aging self (if we are lucky enough to age, that is), but also often prevents us from engaging with people who are the same age as we are or older, mostly driven by the fear of aging and looking like we’re aging. Internalized ageism offers a “safe haven and buffer zone for older persons to stretch their middle-aged identity and at the same time distance themselves from being labelled as members of the ‘old age’ cohort,” according to one study.

Age discrimination is real

This is not something we actively choose to do, however. As Yale professor and expert on the psychology of aging Becca Levy suggests, we don’t necessarily realize that we are internalizing the negative stereotypes about older people that we absorb throughout our lives, starting in early childhood, through all sorts of societal messaging, whether from movies, TV shows, advertising, or social media.

For example, one longitudinal study of Belgian fictional movies found that although older women were featured more often than older men, they were often portrayed as “shrews” or “cranky.” In addition, the older actors were overwhelmingly white, middle-class, able-bodied, and heterosexual (if sexuality was even addressed). They were also what are considered “young-old”—those under age 75. As Levy writes in her 2022 book, Breaking the Age Code:

Most of us like to consider ourselves as capable of thinking fairly accurately about other people. But the truth is, we are social beings who carry around unconscious social beliefs that are so deeply rooted in our minds that we don’t usually realize they’ve got their hooks in us. For better or for worse, those mental images that are the product of our cultural diets, whether it’s the shows we watch, the things we read, or the jokes we laugh at, become scripts we end up acting out.

One 2019 study found that, distressingly, we start to develop more stereotypes and prejudices about aging as we age, even while becoming less anxious about our own aging. In fact, older people tend to be more prejudiced about people in their own age group than younger people are, as they try to differentiate themselves from those older than they are.

This doesn’t just play out in romantic relationships, but also in health care situations. Physicians aged 70 and older who were still in practice had much more negative attitudes toward older people than other age groups, especially if they had been in practice for many years. Perhaps that’s because they’ve had many years of treating older people with various health issues and project what may be ahead for them.

It isn’t just heterosexual people who walk around with internalized ageism. Gay men are acutely aware of how their gay peers view aging and so tend to be more ageist, are more fearful of being seen negatively as they age, and focus more on their own physical attractiveness then lesbians do, according to one study. As Sonya Arreola, research director for UCSF’s Openly Gray: Older Gay Men’s Health Study, notes, “the emphasis on physical attraction and sexual appeal in gay men communities tends to heighten ageism.” Internalized gay ageism leads many middle-aged and older gay men to feel invisible and devalued.

Still, more same-sex spouses—5%—have an age difference of 20 years or more compared with a mere 1% of heterosexual married couples, according to the U.S. Census.

And perhaps not surprising given how much emphasis society puts on women’s beauty and youthfulness, older women tend to be more fearful of their own aging, no matter how positively or negatively they perceive societal stereotypes about aging—what’s known as gendered ageism.

No one is getting any younger

The late gerontologist Bernice Neugarten was the first to notice the rise of what she called the “young-old,” people between the ages of 55 and 75, whom she believed offered “enormous potential as agents of social change in creating an age-irrelevant society and in thus improving the relations between age groups.” In his 1989 book, A Fresh Map of Life, the late historian Peter Laslett expanded on her work by introducing the idea of a “third age,” the years after breadwinning and child-rearing and typically associated with retirement, and a “fourth age,” the final years before death, often considered as involving dependency, decline, and disability.

Ageism is still considered a major societal issue with huge effects on our physical and mental health as well as general well-being—even decreasing longevity, according to the World Health Organization, so we are hardly anywhere near an “age-irrelevant society.” That said, the world is getting older—by 2050, there will be 2.1 billion people across the globe aged 60 years and older. The number of persons aged 80 years or older is expected to reach 426 million by 2050.

In other words, there will be a lot of older adults. Will that make society more or less ageist?

Rather than wait to find out, each of us can try to fight our own internalized ageism. Levy suggests following what she calls the ABC method:

- Awareness of our own attitudes and societal messaging about aging;

- Blaming ageism and not aging per se; and

- Challenging inaccurate and negative age attitudes instead of ignoring them.

Who wouldn’t want to live in a world with what Levy calls “an age-thriving mindset”? Still, that may not change what many of us seek in a romantic partner later in life, especially women who say they are done with providing intensive caregiving.

There’s no way to know if Owens’ initial desire for a younger romantic partner is driven by internalized ageism or something else. As The Golden Bachelor went on, he eliminated the youngest and the oldest of the women vying for his affection. The ones who are still in the running (as of this writing) are indeed all younger than he is—and who knows what kind of internalized ageism they carry around?

But any bachelorette of any age who becomes his romantic partner should be aware that Owens sustained numerous injuries, including to his head, in his nine-season football career as a linebacker for the Los Angeles Rams, which led him to become a lawyer representing athletes with sports injuries. It might also result in him developing chronic traumatic encephalopathy, a type of brain injury, as he ages. That may be a risk some women don’t want to take.

Which is why it could be that whomever he picks may decide that he’s just too old for her.