“This is gonna be the biggest movie ever.” James Cameron was right. Titanic, which premiered 25 years ago this month, was a beast. Not content with being the most expensive film ever made, it would go on to become the highest-grossing of all time, earning well over $2 billion, not to mention a wheelbarrow full of Oscars. When it was finally knocked off its perch in the box office records, it was by Avatar, a film directed by exactly the same man.

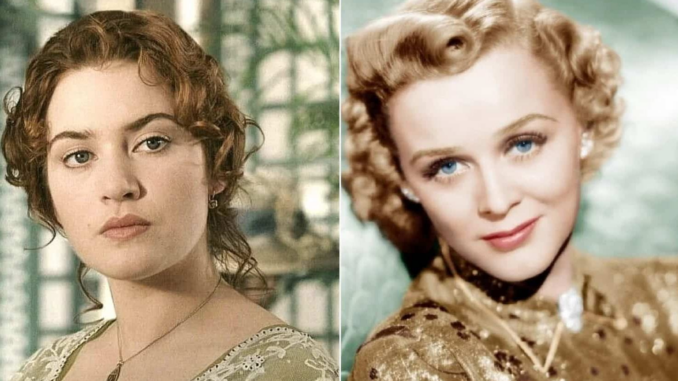

But, judging by the accounts of the people on set, Titanic’s success was not achieved without turmoil and tears. “It was the hardest film absolutely I’ve ever done,” said a then 21-year-old Leonardo DiCaprio. “There were times when I was genuinely frightened of him [Cameron],” said Kate Winslet, who, also 21, was afraid she was going to drown while filming some of the underwater scenes, and was cruelly called “Kate Weighs-a-lot” by Cameron. “Jim has a temper like you wouldn’t believe.”

Last week, Winslet – who stars in the upcoming Avatar sequel – acknowledged Cameron was under immense pressure. “In those days there was no space for him to say, ‘It might not work.’ He had to make it work. There were all those conversations about this huge film, Titanic. I can’t imagine the pressure.”

The film was never an obvious moneymaker. When Cameron pitched a $120 million drama “about feelings” to Fox, he remembers them saying, “Okaay – a three-hour romantic epic? Sure, that’s just what we want. Is there a little bit of Terminator in that? Any Harrier jets, shoot-outs, or car chases?” In addition, Cameron was clearly unimpressed with DiCaprio’s negative energy when the actor turned up to audition with Winslet and, initially, refused to read. DiCaprio too needed a lot of convincing about the project. He said at the time, “My opinion of huge movies like this that are special-effects-oriented has always been to stay away from them ‘cause they seem to me to lack a lot of content.”

The film recruited a huge number of British actors, on account of the ship having been built in Belfast and set sail from Southampton on its doomed journey to New York City. James Lancaster, who is Irish and played the real-life passenger Father Byles, remembers being so committed to his part that he learned the entire Book of Revelations passage that his audition required. He then had to travel to Dublin for his father’s funeral. There, his brother presented him with a passage to read at the service. It happened to be, word for word, the exact speech Lancaster had learned for the audition.

The bulk of Titanic was filmed in Rosarito, Mexico, where the crew built a model of the ship that was around 775 feet long, almost 90 per cent of the size of the original passenger liner. Jason Barry, another Irish actor, who played Tommy Ryan, is one of many who remembers the colossal size of the operation. “It was one of those last movies where they actually built it. I had never been on anything of that scale.” The ship sat on the coast of the Pacific Ocean in a purpose-built 360,000-square-foot pool that could house 17 million gallons of water. To anyone looking at it from the street, unable to see the scaffolding and mechanics behind it, it would have appeared to be the real thing. The actors remember it being beautiful. “My father was literally in tears when he saw this ship all lit up with smoke coming out of the stacks,” says Mark Lindsay Chapman, who played Chief Officer Wilde.

The front section of the ship was on hydraulics, meaning that as the boat began to capsize it could be tilted into the water. The end of the boat, approximately 100 feet long, could tilt up to 90 degrees until its nose was in the air. “At about 40 degrees you started slipping,” says Lancaster. “It’s hard to show on film how terrifying it was.” For many, this – along with the production’s attention to detail, down to using exactly the same engraving on the cutlery – made the replica feel eerily convincing.

Around 150 stunt performers worked on the film’s gargantuan number of physical sequences, and, as the sinking was simulated, they slid down the deck (some with rollers attached to them) into rubberised components of the ship; some were on cables; dozens leaped off the ship, landing inches away from one another. “How nobody died on that, I think is pretty crazy,” says Lancaster.

The reason nobody died was that the stunts were carefully orchestrated. Simon Crane was the film’s stunt coordinator. He remembers Cameron showing the team a model of the boat, which he tilted to 90 degrees. He proceeded to drop little model people “like a handful of marbles” onto the miniature. “This is what I want to see,” he said. Crane and his crew put down thousands of boxes – later transformed to water by CGI – for the stunt performers to jump onto.