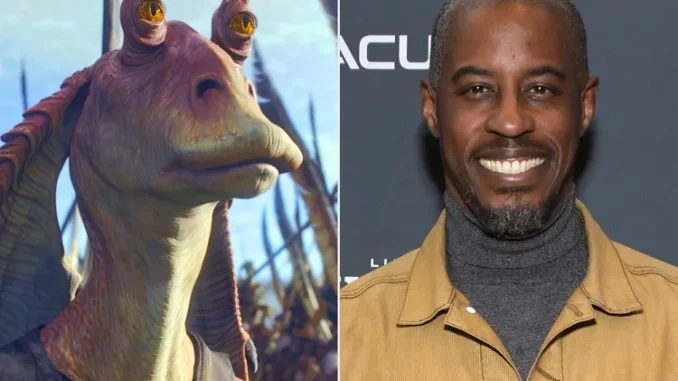

In a wide-ranging interview with PEOPLE, Ahmed Best looks back on the making of ‘The Phantom Menace’ for its 25th anniversary

Ahmed Best made history in 1999 as Jar Jar Binks in the Star Wars universe, and it’s something he still holds close to this day.

Aside from being the occasional comedic relief as the “clumsy” Gungan who “failed upward” in a galaxy far far away, Jar Jar’s inclusion in Star Wars: Episode I — The Phantom Menace 25 years ago also marked a major milestone in the film industry.

Jar Jar was the first main character in a feature live action film to be created through motion-capture technology — and Best was the first actor to play such a role.

But as he now tells PEOPLE, the negative feedback to the character — and targeted harassment from some Star Wars fans — that followed the film’s release stopped him from continuing to work for some time after.

“Everybody came for me,” he recalls, as Phantom Menace returns to theaters for its 25th anniversary. “I’m the first person to do this kind of work, but I was also the first Black person, Black man.”

Despite The Phantom Menace making over $1 billion at the worldwide box office in 1999, Best says he was “ostracized” from doing similar motion-capture work in Hollywood due to the widespread criticism his character received at the time.

Best, now a 50-year-old educator, father, and co-founder of the AfroRithm Futures Group, remembers all the pivotal moments that led up to being cast in The Phantom Menace when he was a young actor in his 20s. He was touring with the Stomp dance troupe in 1997, when a casting director offered him an audition at Lucasfilm’s Skywalker Ranch thanks to his skills on stage.

The performer soon scored both the physical role of Jar Jar (for which he channeled Buster Keaton and Jackie Chan in Drunken Master) and later the voice role, which he debuted for his cast mates — Liam Neeson, Jake Lloyd, Ewan McGregor, Natalie Portman and others — at a table read some time later.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(749x0:751x2):format(webp)/jar-jar-binks-ahmed-best-natalie-portman-star-wars-the-phantom-menace-042924-1-50e0e2937a6e4551aa12256296727d6b.jpg)

“This was the first time I was going to do the Jar Jar voice in front of people. And to be honest, I didn’t know if I was going to do it at that reading or not. I was like, ‘I might do it, I might not.’ And as I’m reading as the first few pages go by, I’m in my head, ‘Do I do this voice? Do I not do this voice? What do I do?'”

“Liam has this wonderfully resonant Irish, Mid-Atlantic voice that will just melt you. You know what I’m saying? So I was just like, ‘Everybody sounds so good. Am I going to do this voice or not?’ And then I see the character name coming up and I was like, ‘F— it.’ And I just do it,” he recalls. “And everybody in the room goes crazy for it. So I was like, ‘OK, all right. I got that one out. I’m supposed to be here now.'”

On set, Best recalls getting along great with the rest of the cast. While principal photography took place over four or five months in England, Best also journeyed back and forth from New York to Industrial Light & Magic’s studios in San Francisco for two years to complete the CGI requirements of the role. The actor remembers Portman being his “little sister” on the film, Neeson as a “fantastic person” to do scenes with, and says he and McGregor were “very much on the same wavelength” because they both grew up watching George Lucas’s original trilogy.

“Everybody was respected, and nobody was bigger than the work,” Best recalls of filming in England. “And I think that was the ethos that we took into doing the prequels. Star Wars is always going to be the thing. That’s the thing we’re working towards. So as much as we can make this world believable, these characters believable, these situations believable, that’s what we’re going to be. We’re not going to be stars above Star Wars. There’s nothing bigger than Star Wars. And I think that’s what made our cast really, really special.”

As Best remembers, the cast was “in our little bubble” while filming the first major Star Wars movie in 16 years.

“So when you come out of that bubble, you’re like, ‘Oh man, everybody’s going to enjoy what we just did, because if you feel the way we felt while we were creating, it’s going to be amazing,” he explains. “But there were already kind of preconceived ideas about it, and there is already bubbling under, this online hatred. It was already being talked about even before the movie dropped.”

The online hate, which Best calls “the first textbook case of cyber bullying,” only grew after the release of the film in May 1999. And it was largely directed at not just Jar Jar as a character, but also Best, who received death threats over his performance. Some critics also considered the character a racial stereotype, which Best has previously addressed on multiple occasions.

“It really wasn’t easy,” he recalls of the backlash. “I was very young. I was 26. And it’s hard to have this idea that the thing you’ve been working all your life for, you finally get it and you’re finally in the big leagues and the highest level of the game, and you hold your own. All of these years you’re just like, ‘I belong at the top of the game. I belong at the highest level.'”

“And then all of a sudden people pull the rug out from under you. And I was just like, ‘What is happening now?’ My career began and ended. I didn’t know what to do, and unfortunately there was really no one that could help me, because it was such a unique position; it had never happened before in history,” Best continues. “Especially with the internet component. Now there’s an entire field of psychology based on it. But at the time, what do I say to a psychologist? I just tried to do the best job that I could do. But George [Lucas] is untouchable and everybody was untouchable. Who wasn’t untouchable? Me. Everyone came at me.”

Best has previously opened up about what soon followed, when he contemplated taking his own life during an early morning on the Brooklyn Bridge.

“I didn’t want to hurt my family like that,” Best now shares. “So it was something bigger than me that made me walk away. I still was lost. I still couldn’t find my footing, and I just felt the injustice of it all. How could I have achieved such a wonderful thing, and then nothing? Nothing. I was longing to continue. I wanted to continue this work. I wanted to continue moving in this direction and seeing what the CGI thing could turn into.”

After deciding to leave New York for Los Angeles (“Walking those streets just hurt”), the Star Wars alum had a difficult time trying out for new roles, having to convince casting directors that he was Jar Jar, and that the character was not simply just computer generated. “I was carrying this weight that it was just hard to shake.”

Best says it also wasn’t easy to see his Star Wars role “diminish and disappear” in the two prequels that followed — specifically 2005’s Revenge of the Sith. After all, like many fans, he hopes to eventually find out about Jar Jar’s fate.

“I would love just for there to be some really good closure, just to know what happened to Jar Jar. And then I don’t think it needs to be tragic,” Best says.

“There was this one piece of Star Wars literature where Jar Jar ended up being this homeless clown in the streets begging for money or something like that. And I was like, ‘I don’t think so. I don’t think that’s Jar Jar’s fate.’ Jar Jar was spectacularly clumsy and failed upwards. He just was just wonderful character that always found a way to succeed. And I would love to know Jar Jar’s fate from there, even if it’s a scene that closes it.”

After overcoming all he has, Best is now in a good place. He’s worked as an adjunct lecturer at USC, appeared in Disney+’s Star Wars series The Mandalorian, and is most importantly a proud father of a 15-year-old son who “gets all my attention.”

His son used to be a big Jar Jar fan too, and as Best jokes, now he just wants to be like Samuel L. Jackson’s Mace Windu. Best’s son was also the reason he even decided to open up about his mental health in the first place.

“I had to let this out. I had to let people know that this happened. This was a thing,” he says. “Because no one should ever have to feel like that, to that extreme.”

“We need to be here for another, we have to take care of each other. We have to be careful with one another regardless of what you do. Just because you’re on a screen doesn’t mean you don’t have any feelings,” Best adds. “We have to be careful with the people that are giving us the opportunity to be emotional, because that’s what we are as performing artists.”