The 1960s were an eventful and divisive time for the United States. Public discourse revolved around the Vietnam War, the Civil Rights Movement, and the sexual revolution. John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King Jr., and Malcom X were all assassinated. The Cuban Missile Crisis, Tet Offensive, My Lai Massacre, and failed Bay of Pigs invasion consumed public attention. Woodstock, hippies, and psychedelic drug culture emerged. For a complete list, just listen to Billy Joel’s song “We Didn’t Start the Fire.”

Although each of these topics featured prominently in the evening news, they were generally absent from primetime television—a strange thing to imagine now, when so much of the entertainment we consume reflects the problems of our society. Instead of programming grappling with the carnage of war or the virulence of racism and sexism, Americans in the sixties were fed what The Atlantic’s Ronald Brownstein calls “banal comedies celebrating the simple wisdom of rural life, including The Beverly Hillbillies and The Andy Griffith Show.”

These were stories that, despite claiming to be set in the United States, actually took place in an alternate dimension, one where conflict could not be anything but the result of miscommunication, and each episode was tied up with a pretty bow, hugs or tears, and a platitudinal life lesson or two.

Television may well have stayed in this dimension were it not for the unexpected and explosive success of a sitcom called All in the Family. Created in 1971 by the late screenwriter-producer Norman Lear, the series revolves around the now all-too-familiar—but at the time totally unprecedented—concept of a dysfunctional family divided by generational differences in their most basic values.

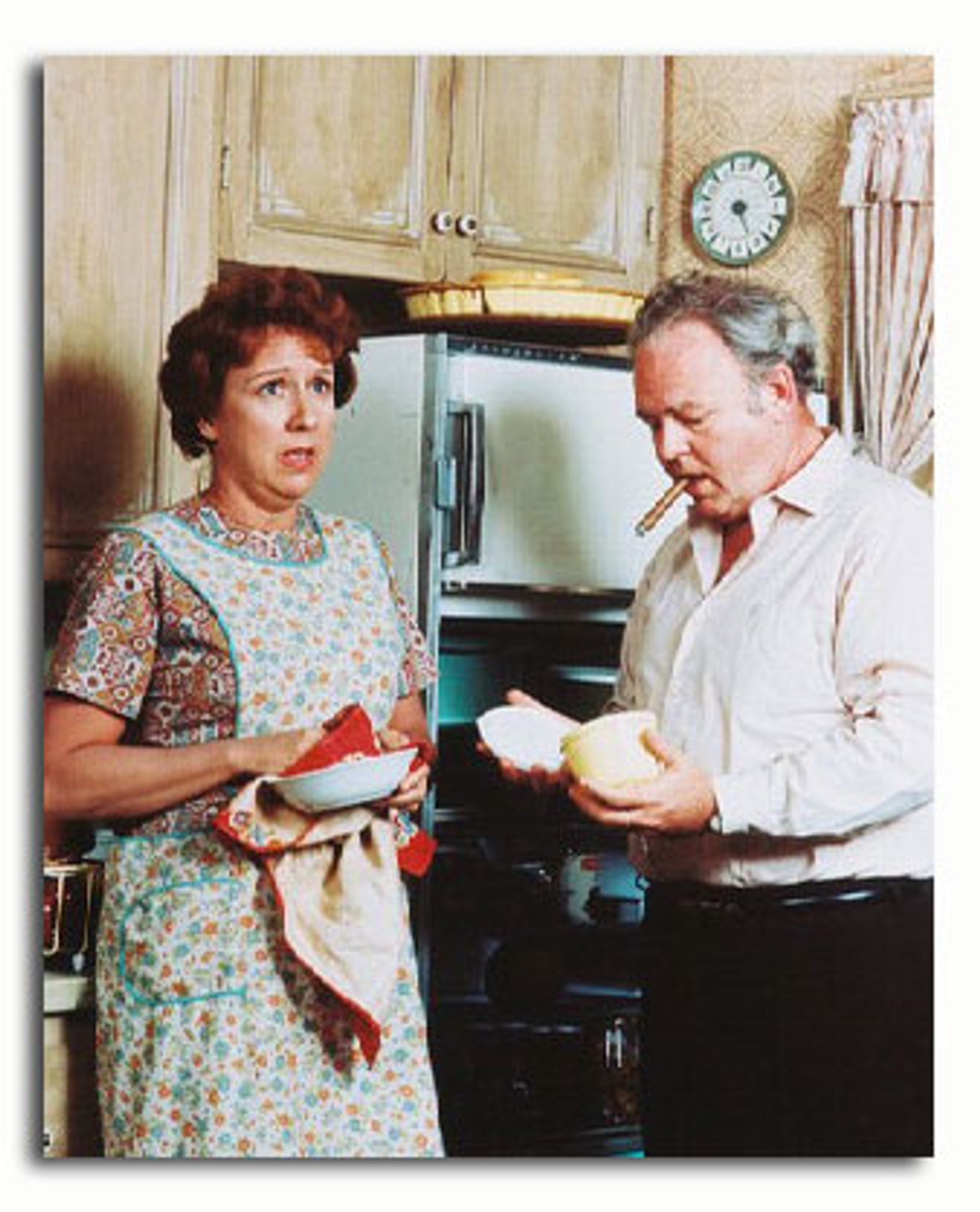

At its center was Archibald “Archie” Bunker, a foul-mouthed, cigar-stomping, Nixon-loving dock worker who lorded over his kind, uneducated wife Edith while butting heads with his rebellious daughter Gloria and her long-haired, peace-loving, progressively-minded husband Michael.

If the characters of The Beverly Hillbillies and Andy Griffith lived in a bubble where no real-world events could hurt them, All in the Family—with episode titles like “The Draft Dodger” and “Gloria Discovers the Women’s Lib”—left no societal stone unturned. Each week, the Bunkers confronted all kinds of contemporary social issues, from discrimination to conscription to gentrification. And each week, the audience could count on Archie (played by Carroll O’Connor) to dictate his unsalted opinions on those issues. The Bunker patriarch was unapologetically racist, sexist, and xenophobic. He based his belief in men’s superiority to women on a mistranslation of the Book of Genesis, repeatedly argued in favor of racial segregation, and took great pleasure in throwing the word “homosexual” around as an insult.

The critical and commercial success of All in the Family—which held the title of America’s most-watched show for a record-breaking period of five consecutive years following its release—makes Archie’s character all the more problematic. While media scholars continue to debate whether Lear’s sitcom, in Brownstein’s words, “punctured or promoted bigotry,” Lear himself argued the Bunker patriarch was meant to drive conservative America to some long-overdue introspection. In retrospect, he did the very opposite.

Fearing the show’s explicit dialogue would alienate certain viewers, CBS made sure to start each episode with the following disclaimer:

“The program you are about to see is All in the Family. It seeks to throw a humorous spotlight on our frailties, prejudices, and concerns. By making them a source of laughter we hope to show—in a mature fashion—just how absurd they are.”

According to The New Yorker’s Emily Nussbaum, this message was likely no more effective than the “do not remove under penalty of law” tag on the butt of a mattress. Indeed, Archie proved to be the show’s most popular character. In Sitcom: A History in 24 Episodes from ‘I Love Lucy’ to ‘Community’, media historian Saul Austerlitz writes that “Audiences liked Archie. Not in an ironic way, not in a so-racist-he’s-funny way; Archie was television royalty because fans saw him as one of their own.” L. Benjamin Rosky, writing for Religion & Politics, adds that, “while Archie was supposed to be a satirical cautionary tale of sorts, some still saw a leader of men based on common sense racism and good old fashioned hard work.” He compares the character’s relationship with the American public to that of Donald Trump, noting that, long before the latter’s MAGA campaign took off, people drove around with bumper stickers saying, “Bunker for President.”

Over the course of the show’s nine seasons, Archie left his mark not only on American culture, but also on television. Nussbaum believes he “represented the danger and the potential of television itself, its ability to influence viewers rather than merely help them kill time. Ironically, for a character so desperate to return to the past, he ended up steering the medium toward the future.”

Despite his popularity, Archie had his fair share of critics. American writer Laura Z. Hobson criticized the sitcom’s attempt to present him as a flawed but lovable and ultimately redeemable person. “I don’t think you can be a black-baiter and lovable, nor an anti-Semite and lovable,” she wrote in a 1971 essay for The New York Times. “And [I] don’t think the millions who watch this show should be conned into thinking that you can be.”

Unfortunately, research has proven that certain audiences disagree with her assertions. In a 1974 paper published in the Journal of Communication, psychologists Milton Rokeach and Neil Vidmar found that most conservative viewers didn’t see All in the Family as satirical. Instead, they embraced Archie’s viewpoints as extensions of their own and therefore “saw nothing wrong” with anything he said, not even his frequent use of racial slurs.

“Lear’s series,” Nussbaum reflects, “seemed to be even more appealing to those who shared Archie’s frustrations with the culture around him, a ‘silent majority’ who got off on hearing taboo thoughts said aloud.”

Even though All in the Family concluded back in 1979, it has never been more relevant than it is today. While the series led to the creation of other socially conscious and more politically correct programs like Melrose Place, The Golden Girls, and—to name a more contemporary example—Modern Family, it also paved the way for other bigotry-glorifying sitcoms like Married . . . with Children. Most of all, though, Bunker’s spirit endures in the closed-off hearts and tunneled minds of America’s ultra-conservatives, who no longer feel like they have to keep their most reprehensible opinions to themselves. All because they saw it on television.