In his 2014 memoir, Even This I Get To Experience, producer Norman Lear wrote the following about his then-43-year-old landmark television comedy, All in the Family, and how it came to matter:

“I’ve never heard that anybody conducted his or her life differently after seeing an episode of All in the Family. If two thousand years of the Judeo-Christian ethic hadn’t erased bigotry and intolerance, I didn’t think a half-hour sitcom was going to do it. Still as my grandfather was fond of saying — and as physicists confirm — when you throw a pebble in a lake the water rises. It’s far too infinitesimal a rise for our eyes to register, so all we can see is the ripple. People still say to me, ‘We watched Archie as a family, and I’ll never forget the discussions we had after the show.’ And so that was the ripple of All in the Family. Families talked.

All in the Family premiered on CBS 50 years ago this week on January 12, 1971, leading to a near-decade run. And a half a century later, families are still talking. Because of the difference the series and its writers made.

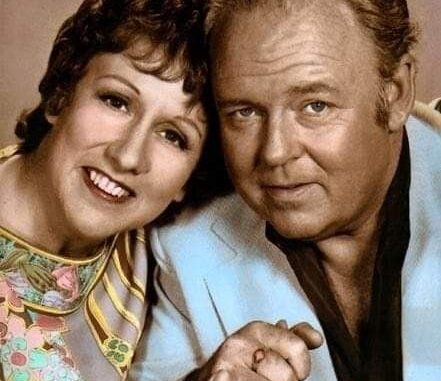

What families mostly talked about back in the 1970s is what they were hearing for the first time on primetime scripted television: real-world, often-heated dialogue fueled by real-world, often-heated societal clashes. A generational comedy that hits home (literally), All in the Family focuses on young liberal newlyweds (the Stivics) living under the same Queens, New York, roof as the bride’s parents, notably her conservative and bigoted father, Archie Bunker. It was a depiction of everyday life that, as these tales tend to go, nearly doomed the series before it even made it to air, bounced twice from ABC after two versions of the pilot were shot there starting in 1968. The topics: sex, religion, social unrest, beliefs. The approach: frank. The language: blunt, even objectionable. The result: “Funny but impossible to air” (as ABC concluded).

Interest from a different network in search of an image shake-up, as well as a third pilot shot with yet another iteration of the cast, landed All in the Family on the air at CBS as a mid-year replacement during the 1970-71 season. season. And in a scheduling decision that bespoke both the network’s solid traditional audience and the show’s poor testing, it premiered on a Tuesday night at 9:30 PM, after Hee-Haw, and preceded by a warning:

The show you are about to see is All in the Family. It seeks to throw a humorous spotlight on our frailties, prejudices, and concerns. By making them a source of laughter, we hope to show — in a mature fashion — just how absurd they are.

A pebble had hit the lake.

In All in the Family, television had what could be described as its first reality show: characters and situations and conversations that viewers recognized as their own. And in the inflammatory early 1970s, reality mattered: The Brady Bunch could exist only so completely against the backdrop of Vietnam. Primetime tells about a real-er life that comes to matter.

It’s not that the Norman Lear series was the first to acknowledge an outside world. When the infant 1950s television came to toddler in the 1960s, several new efforts, from The Dick Van Dyke Show and Room 222 to The Twilight Zone and Ben Casey, explored a more grounded world than I Love Lucy. Race, religion, war. The wholesome Marcus Welby M.D. even touched on abortion. But these were the exceptions, and their real-world threads were external to the fabrics of their shows. With All in the Family, real-world threads became the rule, the points of the show. The series didn’t just offer commentary about the world out there, it addressed it as happening right here. And in how it came to life every week, performed as a stage-play on an inelegant set and recorded with the rawness of videotape rather than the smoothness of film, the real-life connection was reinforced.

We didn’t just watch the Bunkers and the Stivics, we visited them. We knew these people. That was the appeal in homes that tuned in across the country, my large Irish-Catholic working-class family’s Philadelphia home among them. All in the Family marked the first and to my memory only show the nine of us ever watched together as a family on the Good Color TV in the living-room. And while some of the seven children in the room (age range: five to 15) didn’t always get what was there to get, we knew conflict, and we knew funny. That was often enough.

I myself, even at 10, saw pieces of everyone in my family in each fully-realized All in the Family character. And I quickly figured out that my go-to favorite pastime of watching television was now saying something to me, to us, about our actions and their consequences. That we had places in a world larger than the block we lived on. That I had a place. So I made a point to listen.