The title of ABC’s “The Good Doctor” is simple and complicated. Mostly, the show is exactly what it sounds like: a hospital melodrama, with whiz-bang medical science, a dash of intra-staff romance and shameless sentimentality. It’s more competent than good, but it’s well-versed in the workings of the human tear duct.

What makes it distinctive — and possibly what has made it, in its debut season, one of the most-watched shows on television — is the way it interrogates the word “good.” Is there more to it, the show asks, than simply being effective?

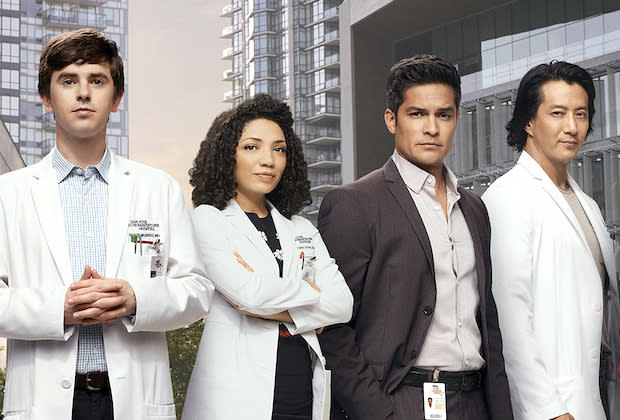

“The Good Doctor” does that, counterintuitively, with a protagonist whose inability to connect emotionally is one of his defining features. Dr. Shaun Murphy (Freddie Highmore), a new surgeon at a prestigious hospital in San Jose, Calif., has autism and savant syndrome.

Earnest but distant, Shaun often needs to have simple responses explained to him, like why parents would be sad to hear that their son is going to lose his leg when the amputation will save his life.

He’s also a brilliant surgeon, able to make intuitive leaps that elude others. (In the mold of difficult-genius dramas like “Sherlock,” “The Good Doctor” visualizes his insights with 3-D graphics, like a diagram of a liver that explodes into segments to explain the function of a key vein.) Still, his skeptical co-workers, like Dr. Neil Melendez (Nicholas Gonzalez), see him as a liability.

“The Good Doctor” is sharp enough to leave open the possibility that they might sometimes have a point. Shaun’s inability to read cues can alienate patients. When he’s cogitating on a diagnosis, he goes blank, like a computer app in spinning-wheel mode, and the show suspends the tension long enough that you, like his colleagues, wonder if something’s gone wrong.

The conceit of “The Good Doctor” is that the condition that limits Shaun’s human interactions is inseparable from his gift. I can’t speak to the accuracy of its representation of autism — I am neither a doctor, nor do I play one on TV — but Shaun’s emotional challenge is the show’s emotional engine.

Shaun may not understand human relations well enough to know that, say, he shouldn’t wake his apartment superintendent after midnight. But Mr. Highmore (“Bates Motel”) makes him appealing and eager, with an unintentionally comic candor. (His version of a reassuring diagnosis: “It’s definitely not flesh-eating bacteria!”) You root for him and for his advocate, Dr. Aaron Glassman (Richard Schiff).

“The Good Doctor” was adapted from a South Korean series by David Shore, the creator of “House,” which had a different sort of difficult protagonist. Dr. Gregory House (Hugh Laurie) was a crusty, arrogant physician in the sharp-elbowed spirit of the post-9/11 aughts, when figures from Jack Bauer of “24” to Simon Cowell of “American Idol” popularized the idea that nice guys don’t get the job done.

On “House,” the doctor’s misanthropy was as much a strength as a liability — his suspicion (“Everybody lies”) and lack of sentiment led him to ingenious diagnoses.

In the “Good Doctor” pilot, Shaun asks something of a dismissive superior that could have been aimed at his TV predecessor. “You’re very arrogant,” he says. “Do you think that helps you be a good surgeon? Does it hurt you as a person? Is it worth it?”

On the page, that sounds sanctimonious and angry, but Shaun asks it out of curiosity. That’s his way. He’s not cuddly or warm, but he’s guileless and well intentioned — the anti-antihero version of Gregory House. Not just Shaun but his fellow young doctors are learning the art of dealing with frightened patients, getting a feel for the proper dosage of tact, honesty, sympathy and willingness to bend rules.

While there may be different ways to be good and to express caring, “The Good Doctor” suggests, it is something worth aspiring to — an idea that may especially appeal to viewers who have experienced health care as scary, impersonal and alienating.

Elsewhere, “The Good Doctor” creates emotional investment the old-fashioned way: by stabbing a hypodermic needle of it straight into your heart.