The “Home Improvement” pilot was in crisis.

As rehearsals got underway on the would-be ABC sitcom in 1991, it became apparent that the central tension between Tim Allen and Frances Fisher, who had been cast as Jill Taylor, the wife of Allen’s character, Tim Taylor, was all wrong.

The show had been built around 37-year-old Allen’s particular brand of machismo stand-up comedy and, opposite his grunts and jabs, Fisher’s comebacks were sounding more like pleas. A test audience watched a run-through of their battle-of-the-sexes repartee in silence.

All year we’ll be marking the 25th anniversary of pop culture milestones that remade the world as we knew it then and created the world we live in now. Welcome to The 1999 Project, from the Los Angeles Times.

“Frances is a very good actress, and her character was upset,” said “Home Improvement” co-creator and executive producer Carmen Finestra. “But the audience was thinking, ‘This guy is a brute.’ You’re not going to feel very sympathetic toward the male character if you feel like he’s abusive.”

Enter Patricia Richardson. The 40-year-old actress was under contract with Disney — which co-produced “Home Improvement” under its former Touchstone Television banner — on a different pilot, and the executives suggested trying her in the role instead. Armed with a stash of withering glares, a no-nonsense Texas twang and a gift for physical comedy, Richardson stood toe-to-toe with Allen when she arrived two days before filming was scheduled to begin.

“Pat made it the comedy that we hoped it would be,” Finestra said. “It was unbelievable what she did. I mean, it made the show work.”

With Richardson as Jill, “Home Improvement” surged ahead to a series order, and it soon became one of the most popular sitcoms of the 1990s — its third season was No. 1 in the ratings, toppling “Seinfeld,” “Frasier” and “Roseanne.” At its peak, an average of 34 million Americans tuned in to the family comedy each week.

“We were weirdly compared to ‘Frasier,’” executive producer Elliot Shoenman said, “in that they were the intellectual show, and we were the everyday-people show.”

From 1991 to 1999, audiences watched the Taylors raise their three sons (Zachery Ty Bryan, Jonathan Taylor Thomas and Taran Noah Smith); laughed at Tim’s mishaps on his cable show, “Tool Time,” alongside his more competent assistant, Al (Richard Karn); and took in the wisdom of the Taylors’ camera-shy neighbor, Wilson (Earl Hindman).

But at the heart of the series was the contentious yet loving relationship between Tim and Jill.

“When I took the job, they said it wasn’t meant to be the Tim Allen show. It was meant to be our show,” Richardson said in a recent interview with The Times, noting, “I’ve always said, I don’t want to play the thankless wife.”

While the Taylors’ home life was one of comforting familiarity, Richardson had a nomadic childhood, thanks to her father’s military career. After a couple of stints in Dallas, she returned a third time to attend Southern Methodist University, where she earned a degree in theater. She worked at a local dinner theater and saved money to pay her way to New York, where she spent more than a decade performing on and off Broadway.

She’d never planned to do TV or film, but when an advertising executive approached her one night after she’d performed an ensemble role in “Gypsy,” she soon booked TV ads for fabric softener and diapers.

“Commercials paid for the theater habit, which didn’t pay at all,” Richardson said.

After relocating to Los Angeles to shoot the Norman Lear sitcom “Double Trouble,” she and her then-husband, actor Ray Baker, made the move permanent in the late 1980s, when she landed lead roles on the short-lived sitcoms “FM” and “Eisenhower & Lutz.”

ABC had been desperate to secure Richardson for “Home Improvement” at the eleventh hour. Richardson was less eager. She’d just given birth to twins a few months earlier, and she had another young son at home. She didn’t feel ready to return to work at all and was especially anxious because the series “was so obviously going to be an enormous hit,” she said.

But the production offered her accommodations, including an extra dressing room to put her twins’ cribs in and a personal driver, so that her nanny could take the babies home early.

“When I took the job, they said it wasn’t meant to be the Tim Allen show. It was meant to be our show,” Patricia Richardson said about “Home Improvement.” (Christina House / Los Angeles Times)

Still, the early weeks shooting “Home Improvement” were difficult. Allen — who had been handpicked by Disney after Michael Eisner and Jeffrey Katzenberg watched his “Men Are Pigs” stand-up set — had never acted professionally beyond commercials. The producers often picked apart his work, and while filming one particularly emotional scene in the first season, Allen panicked when tears began to well in Richardson’s eyes mid-take.

“Tim said, ‘We have to stop the scene. Something’s wrong with Pat,’” series writer and co-executive producer Rosalind Moore recalled. “He thought she was really upset. It never occurred to him that somebody could be so into a scene that they would have a real emotion.”

Eventually, the show found its groove, and Allen and Richardson began meeting regularly with the producers and writers after the weekly read-throughs to give input on their characters and storylines. For Richardson, it was the chance to imbue Jill with depth and humanity beyond her quippy retorts to Tim’s antics.

“Pat was the only woman down on that set almost all of the time, and I was very often the only woman writer in the room,” said Moore. “When she was surrounded by all that testosterone, she would still hold her ground. There were times when she said, ‘You know what? I have three kids. I wouldn’t say this to my children.’ And she was always right. She always made it better.”

But it wasn’t always an easy battle: Richardson remembered one disagreement with the male writers over the way a scene had been written for Jill. When she told them it wasn’t how a woman would react to the circumstance at hand, one of the men chided, “Pat, it’s not like we don’t understand women. We’re married to them.”

As the show entered its third season, Richardson said she was able to renegotiate her contract to be guaranteed four Jill-centric episodes per season, as well as a profit share point, which would give her a back-end percentage of the series earnings.

“I knew that residuals just get less and less, and I felt that I am going to end up being a huge part of whatever this show is,” she said. “It’s going to work because of me almost as much as because of Tim.”

But despite her input into shaping her character and, occasionally, entire episodes of the series, Richardson said she was denied a producer credit out of fear of setting a precedent for other actors. (Allen was an executive consultant in the first season and became an executive producer in the sixth.)

Finestra, who was part of Wind Dancer Productions and co-produced the series with Touchstone, did not recall any conversations around whether Richardson should get a producer credit but said, “That could very well have been a Disney decision.” (Disney Television Studios declined to comment.)

As the character of Jill developed, Richardson received Emmy nominations for her work on Seasons 3, 5, 6 and 7. Allen had received a Season 2 nod, and after his team missed the deadline for Emmys consideration for Season 3, Disney put on an elaborate spectacle the following year, complete with a hot rod and the USC marching band leading a parade to present Allen’s nomination ballot to the Television Academy. But he never received another Emmy nomination for playing Tim Taylor.

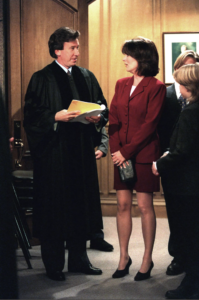

A man in a black robe stands next to a woman in red suit.

Tim Allen and Patricia Richardson on “Home Improvement.” “Pat was the only woman down on that set almost all of the time, and I was very often the only woman writer in the room,” said Rosalind Moore, one of the writers on the series. (Carin Baer / ABC )

“I think that parade turned a lot of people off,” Finestra said. “That just annoyed everybody in the academy, so I think there was some backlash to that.”

And while Finestra didn’t recall any palpable disappointment from Allen over his Emmy snubs, Richardson felt that there was concern from others that the imbalance of recognition might upset her co-star.

“I think everybody was always afraid of making him feel bad,” she said.

To make up for the show’s overall lack of critical acclaim — it ultimately won seven Emmys during its run, all for Donald A. Morgan‘s lighting direction — Finestra created the “Homey Awards,” an in-house talent show where the cast and crew of “Home Improvement” could win every fictional category. The honors even came with a trophy shaped like a giant screw.

“It looked like a penis, of course,” Richardson said.

While filming the show’s eighth season in 1998, Richardson made it clear that it would be her last. She’d gone through a divorce and wanted to be more present in her children’s lives. She had extended her seven-year “Home Improvement” contract to include one more season and negotiated additional profit points, but after shooting more than 200 episodes, in her eyes, this was the end of Jill Taylor.

“I told everybody, there’s not enough money in the world to get me to do a ninth year. This show is over. It needs to end,” she recalled.