The cemetery scene in the 1989 film Steel Magnolias is an all-time, hall-of-fame, best-in-show cry scene, the kind of weighty, deeply emotional piece every actor dreams of playing.

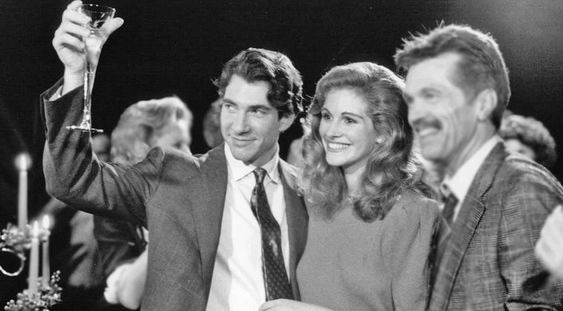

The key reason can be summarized in two words: Sally Field. As M’Lynn, a mother who has just lost her daughter Shelby (Julia Roberts) to complications from diabetes, Field careens through peaks and valleys of grief so raw that you can’t watch it with dry eyes. While pacing through a graveyard, she skates back and forth through the five stages of grief in roughly five minutes, and not one millisecond of it feels false.

Surrounded by her closest friends — Clairee (Olympia Dukakis), Truvy (Dolly Parton), Ouiser (Shirley MacLaine), and Annelle (Daryl Hannah) — M’Lynn starts her extended monologue from a place that sounds at first like stage five: acceptance. “Shelby, as you know, wouldn’t want us to get mired down and wallow in this,” she says. “We should handle it the best way we know how and get on with it. That’s what my mind says. I wish somebody would explain it to my heart.” From there, she recounts the final moments of her daughter’s life, when the machines in the hospital were turned off. “I was there when that wonderful creature drifted into my life, and I was there when she drifted out,” she says, her voice catching. This is when, as a viewer, you know you’re a goner yet still don’t fully understand how devastated you’re about to become.

Field then snaps abruptly from sadness to denial, saying she needs to get back to the rest of her family and checking her face in a compact mirror. Then she instantly dissolves again into grief spiked with extreme rage. “I want to know why!” she cries out, in a scream so primal it seems to come from the deepest cells in her bone marrow. Then she reverts to bargaining — “No, it’s not supposed to happen this way. I’m supposed to go first” — and immediately U-turns and drives right back into anger. “I just want to hit something, hit it hard!” she shouts.

A lesser actor than Field could seem out of control in a scene with so many whiplash-inducing turns, but she finds a way to remain simultaneously anchored and unmoored. No matter how often you watch her work here, it never loses its power.

That’s because Field understood the importance of this scene, which she calls “the crux of the film.” She also credits her co-stars for their support and director Herb Ross for giving her the space to explore so much emotional terrain while the cameras were rolling, though she acknowledges that Ross wasn’t always as flexible with one of her co-stars. That’s just one of the things Field remembers about making this film and preparing for one of the most memorably wrenching scenes of her career.

I’ve read that one of the main reasons you wanted to do Steel Magnolias is because of this scene. Is that true?

Yes. I mean, quite obviously it is a humdinger of a scene. But that scene was the crux of the film, because it is about loss and sadness and grief and rage, but ultimately it’s about friendship. It’s about these women who hang with her. Every step of the journey she takes in that speech — she walks up and down the dirt road of the cemetery and they’re right there with her, feeling it with her, and ultimately they make her laugh. It’s about the very best of what women friends are.

Robert Harling, who wrote the play and the screen adaptation, based the story on his own family and the loss of his sister. How much did that weigh on you while you were making the movie?

It really is my task not to have it weigh on me. I have to pay allegiance only to the text and the actors around me and the world. It is the text that I have to work with, even though Robert and I became very close, and he would tell me things. I could hear that, but I had to be my own M’Lynn.

He didn’t impose any information on me or say “She wouldn’t do that” or “My mother would never act like that.” Bobby knows that an actor has to create something that really joins the information and history on the page, but also the circumstances around you, and most especially the dynamic of all of those other actors.

The thing with film is that good or bad, you need to catch it once. You need to catch this little moment. So it really is about all of those things and then, because of the way I was trained, it is most especially about where all of this links to yourself — your own rage and grief and sadness and loss, and however that manifests itself.

For this scene, was there anything in particular that you were drawing from in your own life?

Well, I can’t talk about those things. As we say, that’s my preparation.

I’ve had actors before, less experienced actors — as I’m listening to music or in my world and trying to stay in that world, they will say “What are you listening to?” and try to pull it away so they can hear. I’ve said before, “Get your prep,” and walked away. [Laughs.] It’s almost how many writers are superstitious that if they tell the story before it’s on the page, they feel it’ll be gone and they won’t be able to write it down. All the things I have ever worked on and anything I’ve ever done just sort of stay with me. And as your life goes on, it expands the repertoire that you can call on.

A lot of people who aren’t actors are impressed by scenes where actors cry. Do you find those kinds of scenes more difficult than ones that aren’t as outwardly emotional?

I mean, they take a great deal of concentration, but there are all sorts of scenes that seem so easy that are so hard to do. This kind of scene, is what it is. You work on it, you work on it, and then you let it fly.

M’Lynn goes through so many different emotional extremes in this scene. Did you lay out when you would hit certain beats beforehand, or did you give yourself some flexibility to go wherever you went in the moment?

The way I’ve been trained because I worked with Strasberg for so long — he believed that you do all of the work before the scene. You do all of the history: What happened the day before? An hour before? What is the weather? How long did it take you to get to the cemetery? Whose car did you ride in? Every single detail of the history of this character, whether it was 15 years ago or two hours ago, and all of the sensory things, of the clothes she has on and the heat and all of those ridiculous things that you think you’ll never use — you have all of that information. And you know the dialogue as well as you know your own name. As Lee would say, the set could go up in flames, and you would still be that character in a flaming set saying the same dialogue, but in a slightly different way because the set is on fire!

If you plan it out beyond that — and I’ve watched this happen — then it cuts you off from being spontaneous to something that’s happening right then and there. Herb Ross just kind of let me go. I didn’t know when I would walk. I didn’t know what I would do. I didn’t know when I would stop. I didn’t really know how it would manifest itself, and then of course, once I did it, there it was: She walks up the cemetery path a little bit, and then she stops and turns around, and then is in denial, raging: “No, no, no.”

In Steel Magnolias, we had this dazzling cast who were so loving and so supportive, and we had become so incredibly close. They were all crying off-camera. Then, when I was off-camera for them, I continued to cry. Then you get weary. There is an actual emotional part of your brain that says, You know what? We don’t want to do this anymore. This is not real and no thanks, we’re not going there. You just shut down. You have to have done it long enough to know ways to get around that.

With your fellow actors who have been off-camera all the time, now they’re on, and then it’s my task off-camera to change it up a little bit, to change the dialogue up a little bit to make it a little more personal, even — not in ways that invade their logic, but in ways that surprise them.