Released 30 years ago, the star-studded melodrama has an uncomfortable message about people who choose to have children despite the medical risks.

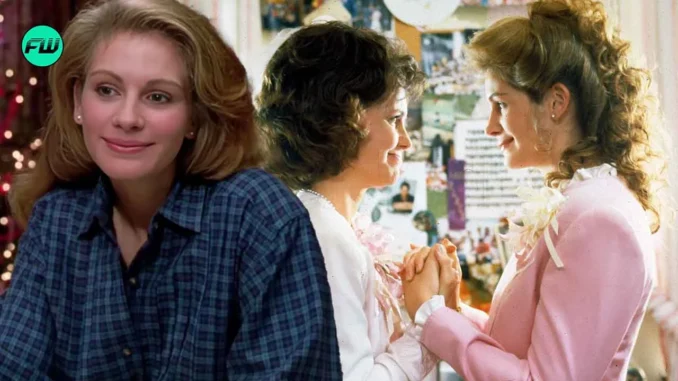

Since its release three decades ago, Steel Magnolias has been hailed as a celebration of women. In his 1989 review of the film, Roger Ebert raved about the dialogue and camaraderie of the ensemble, which includes Dolly Parton, Julia Roberts, and Sally Field. “There may be no movie that better epitomizes the bond of female friendship,” HuffPost declared in 2014. “Mothers share the film with their daughters, teen girls turn to it as a sleepover staple, and men of all ages find themselves taken with the tale of six brassy Southern ladies.” Fans of Herbert Ross’s movie, which played on big screens across the U.S. in May and which is being adapted for stage productions this summer, will recall the tragic central plot: A woman with type 1 diabetes, played by Roberts, has a baby despite her doctor’s warnings and dies a few years later. This premise rarely comes up in analyses of the movie’s emotional power—but it should.

Steel Magnolias is based on a true story. The screenwriter Robert Harling’s sister died of diabetic complications after giving birth in the 1980s, shortly before Harling composed the original play and the film script. If the death of Roberts’s character cements the movie’s status as a feel-good weepy, it also places the narrative within an uncomfortable American cinematic tradition—one in which individuals who reproduce against medical advice suffer terrible consequences. Of course, for many viewers, there’s nothing inherently insidious about the film, which doesn’t have the tone of a morality play. But those revisiting Steel Magnolias this year might consider how it fits into a long history of movies with patronizing, outdated, and sometimes eugenicist implications about who should and shouldn’t have children.

Set in Louisiana, Steel Magnolias begins with the wedding of Roberts’s character, Shelby. The ceremony almost doesn’t happen, because her physician has just told her she shouldn’t conceive to avoid straining her damaged kidneys, but her fiancé insists he loves her all the same. Before long, Shelby becomes pregnant. Her mother, M’Lynn (Field), is furious, scolding her, “There are limits to what you can do.” But Shelby defends herself: “I would rather have 30 minutes of wonderful than a lifetime of nothing special.” M’Lynn tries to “focus on the joy of the situation,” as a friend from her beauty parlor advises, but soon after the baby’s birth, Shelby’s kidneys fail. Shortly after undergoing a kidney transplant, she’s found unconscious at home and later dies in the hospital with M’Lynn at her side.

When it comes to dramatizing the perils of ignoring experts on reproductive matters, Steel Magnolias in some ways recalls the 1917 eugenic-advocacy silent film The Black Stork, in which a couple are told not to marry, because the man has a family history of epilepsy. The couple disregard the advice, and the woman gives birth to a sickly infant. Their doctor refuses care, declaring, “There are times when saving a life is a greater crime than taking one.” The parents almost accept the help of another physician, but the mother dreams of her son growing into a “monstrous” criminal who eventually tries to kill the doctor who saved his life. When she awakens, she refuses medical intervention and allows the baby to die. The infant is shown levitating into Jesus’s arms.

The Black Stork starred and was written by the Chicago physician Harry Haiselden, who controversially and fatally denied care to a baby with partial paralysis. Unlike Harling, who wanted to honor his sister and the women who supported her, Haiselden envisioned that his film would provide instruction on good breeding. Despite some censorship, the movie was a commercial success, as were two other eugenic-advocacy films that year: Married in Name Only and The Garden of Knowledge. The former, a melodrama, depicts a couple who nearly don’t wed, because of the groom’s family history of insanity. (When the two learn that the man was adopted, they feel free to marry and procreate.) Using an Eden-inspired allegory, The Garden of Knowledge depicts the journey of a young college graduate who’s deemed fit to participate in a eugenic experiment after he resists sexual temptation.

Though unwittingly and less explicitly, Steel Magnolias also stirs strong emotions and uses archetypal characters to convey a moral about forbidden longing. As a Chicago Tribune reviewer observed in 1989, M’Lynn is a “self-sacrificing mother” and Shelby is a “tubercular saint”; the latter arouses pity by following her yearning for motherhood to a tragic end. By invoking broader mythic constructs, Steel Magnolias has led some viewers to argue that the medical story line is incidental and that the film is primarily about being grateful and resilient in the face of life’s joys and sorrows. The movie’s emphasis on the cyclical nature of life—the film is structured by the passing of the seasons, starting with spring—reinforces the notion that it’s impossible to thwart the laws of nature.

In this predictably ordered world, Shelby, who is constantly arguing with her mother, is an outlier who at times appears foolish and ornery. Though a sympathetic character, Shelby is depicted as naive from the start. When M’Lynn learns of the pregnancy and restates the doctor’s grave warnings, Shelby doesn’t question the physician’s motivations or expertise; she simply says, “I’ll be careful” and insists she can beat the odds, despite clearly struggling with her health on-screen. By presenting Shelby’s judgment—not her doctor’s—as flawed, Steel Magnolias obscures the fact that eugenic ideals have long tainted the maternal advice and care that people with diabetes in particular receive.

Obstetrical diabetes first developed in the U.S. in the 1920s, when insulin’s discovery enabled women like Shelby to reach reproductive age. This area of maternal medicine was significantly shaped by the social context of the day. The ’20s and ’30s marked the peak of the eugenics movement, and many Progressive-era leaders sought to eliminate defective traits from the gene pool. As a result, many health experts feared that the new treatment for diabetes would interfere with natural selection.

In the first few decades after insulin’s discovery, U.S. physicians commonly advised people with diabetes not to conceive and to have a therapeutic abortion if they did. Like Shelby in Steel Magnolias, many patients took their doctors’ good faith for granted; they shouldn’t have. Physicians often cited the increased risk of complications not as evidence of the need to develop better standards of care, but of the urgency of eugenic practices. To discourage patients from pursuing pregnancy, many doctors also told vivid, alarming tales of mothers and infants dying in the delivery room, not bothering to mention that many of these cases occurred before the discovery of insulin, which improved outcomes (even if didn’t eliminate risks). Practices only changed in the late 1950s after determined women like Shelby got pregnant anyway, enabling one sympathetic physician, Priscilla White, to find ways to help them more safely deliver.

This historical background partly explains the disparity in pregnancy outcomes between diabetics and healthy patients in the 1980s, when Harling wrote Steel Magnolias. Had the medical profession embraced the reproductive rights of people with diabetes from the beginning, the maternal care for women like Shelby might have been more evolved. This context also highlights the difficulty of distinguishing between doctors’ concern for mothers and their concern for society. Steel Magnolias never challenges the wisdom of Shelby’s doctor (whose character never appears on-screen), which may be one reason some viewers see Shelby as guilty of “borderline injudiciousness” at best and as “incredibly selfish” at worst. The film gives audiences no reason to think that women in Shelby’s position aren’t just exercising a strong will but are perhaps revolting against an institution that has done them harm.

As the mother of a child with diabetes, I’m familiar with the kinds of judgments that diabetics in the past have faced. Upon learning of my daughter’s condition, more than one provider has asked, “Did you get genetic testing beforehand?” I’ve also been asked whether I think my daughter will have kids, given the risks. These questions, again, suggest that women who carry or have certain traits might be better off avoiding pregnancy altogether. (Of course, many individuals do consider genetic risks in making reproductive choices, and nothing is wrong with this, provided their decisions are their own.) The pressure not to reproduce can be far more intense for other marginalized demographics: for trans patients, patients of color, and those with lower incomes, groups that have historically been denied autonomy over their own bodies.

Rather than acknowledging the existence of reproductive discrimination, Steel Magnolias normalizes the dire outcomes for women who assert their rights in medical settings by restoring order after Shelby’s death. As the movie ends, it is springtime once again, and M’Lynn pushes her grandchild in a swing, matter-of-factly observing, “Life goes on.” Another character goes into labor with a baby to be named Shelby. Viewers are meant to take comfort in the fact that Shelby’s memory endures with both this new baby and her son, who appears healthy. But for some like myself, such scenes do little to distract from the troubling narrative about diabetic pregnancy within and beyond the film. As fans flock to theaters to see Steel Magnolias this summer, they might consider that—thanks in part to entrenched eugenicist ideas—many people are still struggling for the ability to reproduce without stigma.