The rise and fall of the socially conscious sitcom, from “All in the Family” to “Roseanne”

Fifty years ago, it seemed that the United States was about to come apart over political differences. The civil rights movement, the sexual revolution and the Vietnam War were cleaving neighborhoods and families, and violence was thick in the air. At the same time, Americans were getting used to a pervasive form of technology. It was only in 1954 that most homes had television sets, and by the late 1960s, television was still seen as a gadget offering an escape from reality rather than enlightenment. “The Andy Griffith Show” and “The Lucy Show” were the most-watched programs of 1967-68, both gentle comedies that avoided references to current affairs.

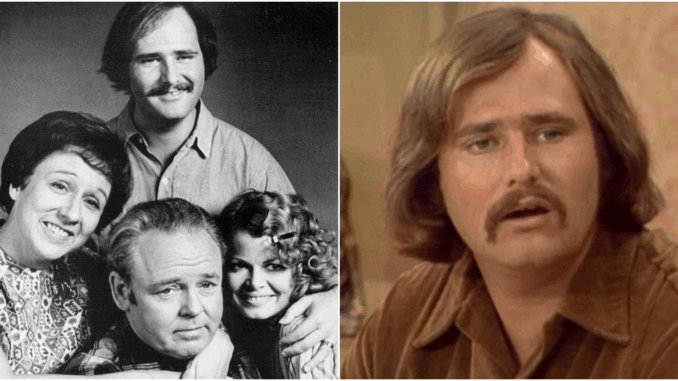

Things changed quickly. The top-ranked show in 1968-69 was “Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In,” a variety hour that machine-gunned jokes about sex, politics and religion. “Laugh-In” led the way, a few years later, to a show that transformed TV. That was “All in the Family,” a socially conscious and enormously popular sitcom in which the central characters argued about presidential politics, the racial integration of their neighborhood in the New York City borough of Queens, and just about any other topic mentioned on the evening news.

The kind of national catharsis delivered by “All in the Family” seems elusive now. In 2018 we are still getting used to the internet, which encourages short-attention-span solitariness rather than family discussions and the chance for reflection that can follow a 30-minute television program. (Imagine saying that in 1968.) Social media has replaced TV, and it figured in the furor over what briefly seemed to be this year’s answer to “All in the Family,” ABC’s reboot of “Roseanne.”

The kind of national catharsis delivered by “All in the Family” seems elusive now. In 2018 we are still getting used to the internet, which encourages short-attention-span solitariness rather than family discussions and the chance for reflection that can follow a 30-minute television program. (Imagine saying that in 1968.) Social media has replaced TV, and it figured in the furor over what briefly seemed to be this year’s answer to “All in the Family,” ABC’s reboot of “Roseanne.”

“All in the Family” was widely praised by critics and won 22 Emmy awards during its 1971-79 run, though some objected that verisimilitude was no excuse for the racial slurs and other vulgarities uttered by the main character, a loading-dock worker named Archie Bunker. As a Richard Nixon supporter in Queens in 1972, Archie probably would have been Catholic in real life, but Norman Lear, the producer, made him a Protestant who made negative generalizations about every almost racial, ethnic and religious group one could imagine—invariably having to eat his words when encountering actual members of these groups. When Archie called for the arming of all airline passengers to prevent hijackings, or claimed that God wanted different races to live separately (“I ain’t no bigot,” he protested in one episode, “I’m the first guy to say, ‘It ain’t your fault that youse are colored”), it was an opportunity for viewers to confront, or at least discuss, their own narrow thinking.

Brilliantly portrayed by Carroll O’Connor, Archie was a complicated character, someone whose racism stemmed from his determination to use any advantage he could to help his family, including white privilege—“motivated not by hatred but by fear,” as Lear once wrote.

Lear and O’Connor were interested not just in ridiculing their character’s racism but in trying to examine its causes. “How could any man that loves you tell you anything that’s wrong?” Archie asks in one episode, explaining how he inherited his racist attitudes from his father. He was a living ethics exam problem for viewers.

One foe of the series was Laura Z. Hobson, who had written Gentlemen’s Agreement, the classic novel about anti-Semitism. She wrote in The New York Times that “All in the Family” “cleaned up” bigotry (by avoiding,

for example, the most offensive racial slur) and argued, “I don’t think you can be a black-baiter and lovable, or an anti-Semite and lovable. And I don’t think the millions who watch this show should be conned into thinking you can be.” Lear responded with a caustic essay in which he asked, “In what vacuum did you grow up? Not a father, brother, uncle, aunt, friend or neighbor who was both lovable and bigoted?”