Dr. Beverly Hofstadter, Ph.D., M.D., may not have been a main character in The Big Bang Theory, but her presence was unforgettable. As Leonard Hofstadter’s emotionally detached, hyper-rational mother, Beverly left a mark — both on Leonard’s psyche and on the audience.

From the moment she first appeared in Season 2’s “The Maternal Capacitance,” fans were introduced to a woman who treated motherhood more like a science experiment than an emotional bond. As she once put it, the only reason she and her husband engaged in coitus was for reproduction and research.

Your Birthday Is Not About You

Leonard once revealed in therapy that he never got to celebrate his birthday. Why? Because, according to Beverly, being born was her achievement — not his.

Instead of getting gifts, Leonard sends her a card with money every year on his birthday. This cold logic sets the tone for Beverly’s entire parenting philosophy: clinical, impersonal, and completely lacking warmth.

Birthdays Are Meaningless Milestones

For Beverly, celebrating the day a child exits a birth canal is illogical. Achievements are to be honored, not biological events.

In fact, the one time Leonard thought his parents were throwing him a surprise party, it turned out to be a funeral for his grandfather. That sums it up perfectly: sentimentality is pointless.

Communication Is Optional

Beverly has a deeply flawed (and ironic) relationship with communication. Despite being a neuroscientist and psychiatrist, she shows little interest in meaningful dialogue with her own son.

In one episode, Leonard discovers she’s closer to his roommate Sheldon than to him — a revelation that only deepens his emotional wounds. Even when she meets Mary Cooper (Sheldon’s mom) and momentarily questions her own approach, she quickly dismisses it. After all, reflection isn’t her strong suit.

Sibling Comparison Is a Must

Beverly constantly compares Leonard to his more “accomplished” siblings — a brother who’s a Harvard professor and a sister conducting diabetes research.

Leonard once had to return a science fair ribbon because his brother had done the same experiment at a higher level. Even in adulthood, Beverly brushes off Leonard’s accomplishments (like getting married) as trivial in comparison to his siblings’.

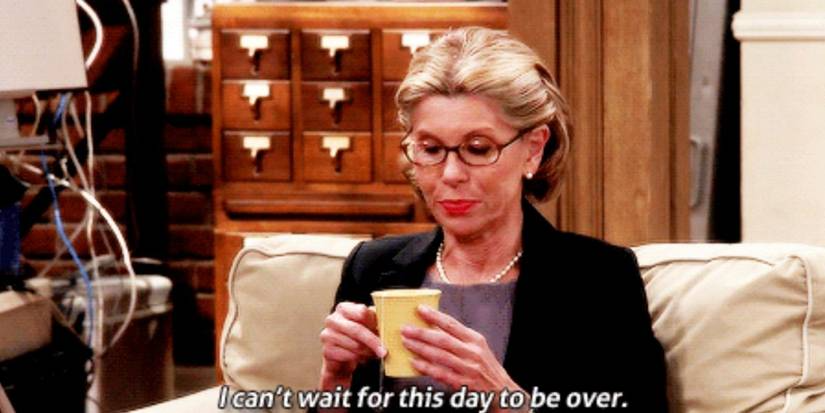

Emotional Validation? Not Her Style

Perhaps the most painful part of Beverly’s parenting is her complete lack of approval. She’s never told Leonard she’s proud of him, and only seems impressed by people like Sheldon — who reflect her own cold, intellectual nature.

When Leonard once asked for relationship advice, her only words of support were: “Buck up, sissy pants.” That’s about as affectionate as she gets.

Publishing Your Child’s Flaws Is Acceptable

In a particularly awkward moment, Leonard’s wife Penny discovers that Beverly wrote a book titled “The Disappointing Child” — based on Leonard’s shortcomings.

Even more ironic, Penny was assigned to read the book in one of her college classes. That revelation made it painfully clear how little Beverly values her son’s privacy or dignity.

Be Closer to Your Son’s Roommate Than Your Son

Beverly’s strange attachment to Sheldon is a major source of tension. She’s more emotionally engaged with her son’s best friend than with Leonard himself — something Leonard discovers the hard way.

Sheldon knew intimate family details (like the death of Leonard’s uncle and childhood dog) before Leonard did. That’s not just neglectful — it’s emotionally damaging.

Never Offer Unconditional Love

Unlike Mary Cooper, who showers Sheldon with unconditional love despite his quirks, Beverly believes this kind of affection is harmful to a child’s development.

She only attempts to show Leonard affection after seeing how well Mary’s parenting “worked.” Unfortunately, the result is awkward and stiff, making both mother and son deeply uncomfortable.

Turn Potty Training Into a Science Experiment

One of the strangest insights into Leonard’s childhood came when he described being potty trained — while electrodes were glued to his head to monitor brainwaves.

While Sheldon saw this as enviable and “educational,” Leonard saw it for what it was: cold, detached, and utterly inappropriate for a child’s early development.