When Celebrities Find Themselves in Robert Pattinson’s Art After Twilight

The shadow cast by a global phenomenon like Twilight is gargantuan, capable of swallowing careers whole. For many, it would have been a comfortable, if artistically stifling, cage of glittering vampires and brooding heroines. But for Robert Pattinson, the journey “after Twilight” was less an escape and more a deliberate, meticulously orchestrated artistic metamorphosis. It’s a compelling case study of how a celebrity, trapped by the overwhelming success of a single role, can truly find themselves – or, more accurately, allow the world to find them – in the challenging, often uncomfortable, embrace of their subsequent art.

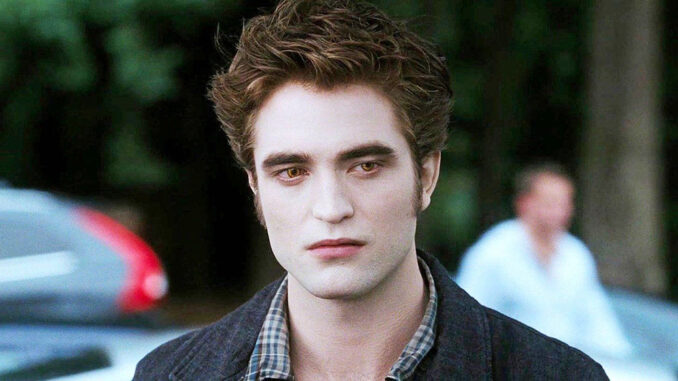

For years, Robert Pattinson was Edward Cullen. His face, his gaze, his very essence seemed to be inextricable from the romanticized vampire that captivated millions. This ubiquity was a double-edged sword: immense fame and fortune, but also a relentless typecasting that threatened to define his entire professional existence. The challenge for Pattinson, and for any actor in a similar predicament, was not merely to shed the skin of his most famous character, but to actively sculpt a new, undeniably distinct artistic identity. He achieved this by making an almost militant pivot towards independent cinema, auteur directors, and roles designed to actively dismantle any lingering traces of the heartthrob persona.

The pivot wasn’t merely a change of genre; it was a radical re-imagining of what kind of actor Pattinson wanted to be, and what kind of art he wanted to make. He didn’t chase blockbuster sequels or rom-com leads; instead, he plunged headfirst into the often-abrasive, psychologically intense worlds of directors like David Cronenberg, the Safdie brothers, Robert Eggers, and Claire Denis. This wasn’t a casual exploration; it was a commitment to roles that were often grotesque, unlikable, physically demanding, or just plain weird.

Consider his collaboration with David Cronenberg, starting with Cosmopolis (2012). Here, Pattinson played Eric Packer, a billionaire asset manager traversing Manhattan in a limousine, his life slowly unraveling amidst philosophical diatribes and an almost clinical detachment. It was cold, cerebral, and utterly devoid of the warmth or tortured romance that defined Edward. Audiences watching Pattinson deliver lines about “the logic of the rats” or experience a surreal proctological exam were forced to confront a radically different performer – one who embraced discomfort and intellectual complexity. He wasn’t trying to be Edward Cullen; he was actively, almost defiantly, being someone else entirely.

This pattern intensified. In David Michôd’s post-apocalyptic The Rover (2014), Pattinson played Rey, a slow-witted, wounded accomplice in a desolate Australian landscape. Grimy, vulnerable, and physically raw, it was a performance that spoke volumes about his willingness to strip away glamour and ego. But it was arguably with the Safdie brothers’ Good Time (2017) that the collective gasp of surprise truly became a resounding hum of critical reassessment. As Connie Nikas, a small-time crook embarking on a desperate, feverish, neon-drenched odyssey through New York City, Pattinson delivered a performance of raw, frantic energy. He was charismatic, repellent, and utterly captivating – a far cry from the brooding vampire, and a testament to an actor capable of true transformation. Here, in the grimy, propulsive art of the Safdie brothers, Pattinson found an artistic freedom that allowed him to express a new, intense facet of his talent. The film wasn’t just good; it showcased an actor reinvented.

Then came Robert Eggers’ The Lighthouse (2019), a black-and-white, sea-mad, gas-fumed fever dream where Pattinson, alongside Willem Dafoe, descends into madness as a 19th-century lighthouse keeper. His physical commitment, his transformation into a grimier, more unhinged individual, and his mastery of an antiquated accent were total. It was a performance that demanded full immersion, showcasing a complete dedication to the craft that simply wasn’t visible behind the layers of teen idol veneer. In these roles, critics and audiences alike began to see not a former teen idol, but a serious, committed artist. He wasn’t just in these films; he was integral to their artistic vision, shaping them with his newfound range and fearless choices.

The journey culminated, in a way, with his return to more mainstream fare, but on his terms: Christopher Nolan’s Tenet and, most notably, Matt Reeves’ The Batman. His Batman is a troubled, reclusive, almost gothic figure, imbued with the same internal angst and intensity he honed in his indie work. He brought the complexities of his arthouse characters to a blockbuster, demonstrating that his self-discovery through art wasn’t just about escaping; it was about elevating.

Robert Pattinson’s post-Twilight career is a potent blueprint for artistic liberation. It’s a testament to the power of deliberate choice, of valuing artistic integrity over commercial safety, and of seeking out collaborators who push boundaries. For other celebrities burdened by singular, colossal successes, Pattinson’s trajectory offers a profound lesson: the path to finding oneself, to earning a new respect and critical acclaim, often lies not in shying away from one’s past, but in bravely embracing the challenging, sometimes uncomfortable, and always transformative embrace of new art. It is in these carefully chosen roles, these collaborations with visionary directors, that the true artist emerges, distinct and redefined, from the shadow of their former self.