“Boy the way Glenn Miller played

Songs that made ‘The Hit Parade’

Guys like us, we had it made

Those were the days!”

That’s the opening theme to “All in the Family,” which premiered Jan. 12, 1971, 40 years ago today. Revisit the show via DVD or YouTube; it’ll spark an appreciation of what has changed in America and on American TV and what hasn’t — and a realization that a series like this would be unthinkable now.

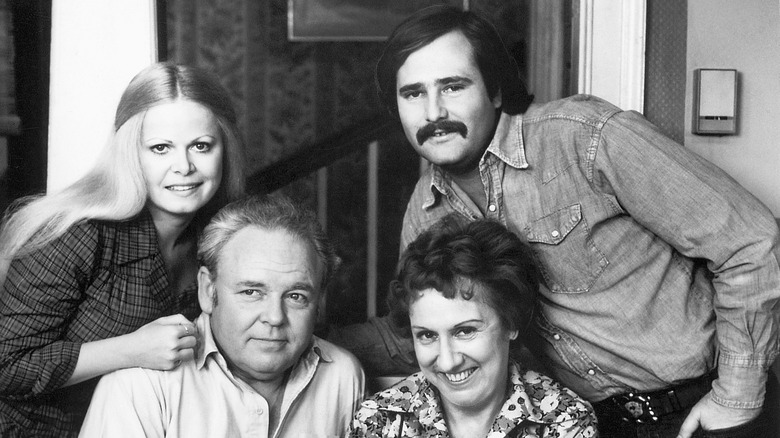

Developed by Norman Lear, the CBS series revolved around a working-class Queens family: Archie Bunker (Carroll O’Connor); his “dingbat” wife, Edith (Jean Stapleton); his daughter, Gloria (Sally Struthers); his liberal son-in-law, Mike “Meathead” Stivic (Rob Reiner). The plots contained some of the expected sitcom fodder: misunderstandings, silly deceptions, crises that turned out to be no big deal. But the heart of the show was topical humor. The Bunkers and their friends and neighbors debated war, religion, drugs, gun control, sex, sexism, gay rights, race relations, immigration, taxation, the environmental movement and everything else under the sun. The series wasn’t just a situation comedy, it as was an ongoing national conversation rooted in well-written, well-acted, multifaceted characters.

The historical specifics have changed since 1971, and the language we use to describe them has changed, too. But the cultural fault lines and hot-button topics all have modern equivalents. Racial, ethnic and sexual upheaval? Check. Inflation and unemployment? Double check. Liberal/conservative rancor? And how. Terrorism and war? You better believe it, buddy. (In a 1972 episode, Archie delivered a pro-gun TV editorial that sounded eerily like actual proposals made after 9/11. The solution to skyjackings, Archie told viewers, was to “arm all your passengers … Just pass out the pistols at the beginning of the trip and pick them up again at the end. Case closed.”)

It might be hard for younger viewers to imagine how striking this series was. Prior to the late ’60s and early ’70s, pop culture either made an ostentatiously big show of grappling with hot-button topics (usually in Oscar-baiting message films or dour live TV dramas) or plugged its ears and whistled a happy tune. There was a disconnect between how people talked in private (and what they talked about) and what you saw on TV and on movie screens and heard on the radio. In 1969, when Norman Lear got approval from CBS to create an American version of popular British sitcom “Till Death Do Us Part” — the same concept as “All in the Family,” but less elegantly directed and tonally adventurous — the boundaries that once separated socially aware popular art from mainstream entertainment became porous. Entertainment started to let the world in — and not in dribs and drabs. The floodgates opened. “All in the Family” helped knock them down.

“If your spics and your spades want their rightful share of the American dream, let ’em get out there and hustle for it, like I done,” Archie groused to Mike, who was agitating about civil rights yet again.

“So now you’re going to tell me the black man has just as must chance as the white man to get a job?” Mike demands.

“More,” Archie says. “He has more. I didn’t have no million people marchin’ and protestin’ to get me my job.”

“No,” Edith interrupts. “His uncle got it for him.”

Characters bantered about touchy subjects, often in the presence of the very people who were touchy about them, and they did this in all sorts of TV shows and films, not just ones that were supposed to be Relevant and Important. Gene Hackman’s Popeye Doyle from “The French Connection,” which came out in the fall of ’71, was Archie Bunker’s fantasy supercop, the kind of skull-cracking, pre-Miranda street centurion who would have busted Mike Stivic over the head with a nightstick. (“Um, um, um, um!” Archie says, mocking Mike’s nervous stammer. “You sound like a seal with its throat cut!”) Three years of Lear’s show probably helped prepare audiences for Mel Brooks’ 1974 smash “Blazing Saddles,” a racial burlesque on horseback that you could imagine Archie’s neighbor George Jefferson — a black racist and pioneering small businessman — recommending to everyone he knew. ABC’s brutally violent detective show “Starsky and Hutch” — itself inspired by “Dirty Harry” and “The French Connection” — stole a running gag from “All in the Family”: having black and white characters sarcastically tell members of other races, “You all look alike to me.”

The success of Lear’s show inspired good spinoffs (“The Jeffersons,” “Maude”), bad spinoffs (“Gloria,” “Archie Bunker’s Place”) and one spinoff of a spinoff (“Good Times,” starring Esther Rolle as Florida Evans, Maude’s former housekeeper). The dialogue wasn’t conceived in that post-Clinton, Seinfeld-ian, “Not that there’s anything wrong with that” vein. Some of the nonwhite supporting characters were Sidney Poitier-style credit-to-his-race types to whom Archie could have no rational objection (George’s son Lionel, for example, was a handsome, smiling cipher); but a shockingly high percentage were as warm, flawed and raucous as Archie. Their talk was sometimes smart, sometimes dumb, and nearly always blunt. It was scalding but necessary, like steam from a teakettle.

“I’m gonna go into town and get me a good Jew lawyer,” Archie fumes.

“Do you always have to label people?” Mike asks. “Why can’t you just get a lawyer. Why does it have to be a Jewish lawyer?”

“Because if I’m going to sue an Ay-rab, I want a guy that’s full o’ hate!”

“Racial balance is important in everything,” Mike declares in another episode. “Take education: Why do you think it’s so tough for a black student to become a doctor?”

Archie: “Because nobody wants to see a black guy coming at them with a knife.”

The show’s core sensibility was basically liberal; that’s why Archie got stuck with all the malapropisms. But it would be wrong to claim that the series had no sympathy for Archie, or that he was just a rhetorical punching bag, or that Mike was intended as a righteous truth-telling character, a mouthpiece and role model for enlightened Americans. O’Connor was such an appealing performer — never more so than when Archie dropped the bluster and spoke from the heart — that the character became an emblem of working-class grit and World War II-era resilience. (In one of President Richard Nixon’s secret White House tapes, Nixon and his staff decry the show’s ribbing of Archie and affectionately label him a “hard hat.”) And it certainly wasn’t lost on the writers — or the audience — that Mike and Gloria sponged off Edith and Archie even as they lectured them on the proper way to think, talk and live. Archie ridiculed Mike’s mooching in almost every episode; it was the knockout punch he threw after Mike zinged him with college-kid verbal jabs. (In the episode where Edith befriends a lonely old man at the local supermarket, Mike asks why the fellow can’t live with them, and Archie barks, “Because we’ve already got one freeloader living with me, and bread’s up 10 cents a loaf!”)

The program switched from very broad comedy to kitchen-sink drama and back, so subtly that the shift rarely felt forced. The blocking owed more to televised theater than to traditional three-camera sitcoms. When the characters turned introspective, the camera crept in slowly from a medium shot to a tight close-up, creating a protected space where delicate monologues could flower.

Just look at this extraordinary moment from the 1978 episode “Two’s a Crowd,” in which Archie and Mike accidentally get locked in the storeroom of Archie’s bar and pass the time by boozing and talking. When they’re both stinking drunk, Archie casually states that his father taught him everything he knows. When Mike suggests that Archie’s father was wrong to pass on his bigotry to his son, watch how episode director Paul Bogart zooms in on O’Connor, and how O’Connor morphs from a soused buffoon into an innocent boy who lives in terror and awe of his dad — slowly, patiently, with such grace and concentration that you can hear the studio audience’s laughter dying out like campfire embers, then nervously sputtering to life again. “Your father?” Archie asks. “The breadwinner of the house, there? The man who goes out and busts his butt to put a roof over your head and clothes on your back? You call your father wrong?” As critic Edward Copeland writes, “Those emotional moments on All in the Family could be its strongest ones, topping the laughs.”

TV today is inhospitable to series like “All in the Family.” This is only partly due to TV’s splintering from a handful of channels into hundreds. An equal or larger part of the blame can be laid at the feet of broadcast network executives and their marketers, who figured out (sometime in the late ’80s) that they could make more ad money by junking the “Big Tent” model and appealing to white college graduates with loads of disposable income — a description that rules out anyone who looks or sounds like a character from “All in the Family” (even Mike or Gloria). Except for certain corners of cable — specifically channels that thrive on shows about violent crime and/or revolve around working-class or poor characters — you don’t hear people talking about race, class, religion or politics unless the dialogue is jocular and sarcastic and “just kidding” (like the banter on “Glee” and “Community”) or the earnest centerpiece of a Very Special Episode. And can you remember the last time a broadcast network built a sitcom around 50-something, pear-shaped, working-class married people — of any color? Pretty much every modern sitcom lead is under 40 (or trying hard to look it) and fashionably thin or buff.

Since the early ’80s, the networks have done their best to gentrify prime time, banishing demographically déclassé characters and subjects while retaining elements that marketers call “sexy” (code for “flashily empty”). Little remains of Lear’s legacy but cursing, innuendo and the sound of flushing toilets. The template for most modern network sitcoms is “Friends” — which, contrary to the “Seinfeld” mantra, truly was a Show About Nothing. Modern network sitcoms are mostly about dating, parenthood and office politics; they deal with hot-button issues in a glancing, glib way if they address them at all. Some are lame. Some are amusing. A few are brilliant. None is the equal of “All in the Family.” Those were the days.