The I Love Lucy cast insisted that the show didn’t intend to take on world-changing progressive issues, but it was far more subversive than they let on.

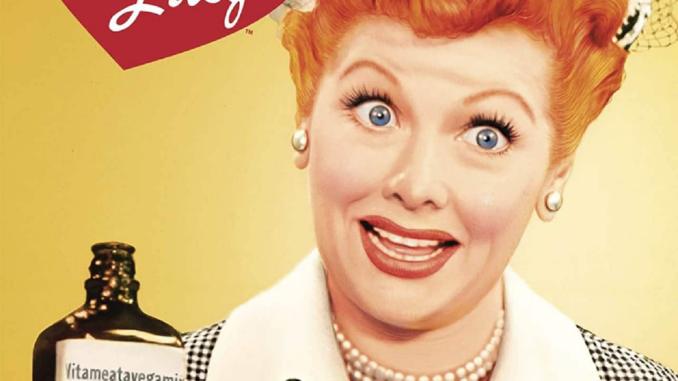

Everyone who has seen the sitcom has a favorite I Love Lucy moment. The show – which celebrated its 80th anniversary this October – has become ubiquitous in American culture, so much so, that it’s become ingrained. Images of Lucille Ball stuffing candy in her mouth, stomping on grapes, or getting sloshed on an alcoholic tonic have become part of the filament of the tapestry of American popular culture.

After the end of the show in 1957, I Love Lucy continued to gain new fans and remind old ones of its brilliance through the magic of reruns. For nearly a century, audiences watched the crazed antics of the blowsy redhead who wormed her way into the hearts of millions of Americans.

Not just a great sitcom, I Love Lucy also charted the American Dream in post-war America. Television was a good tool for propaganda, reminding viewers of what it meant to be successful in America in the ’50s. The vision of the nuclear family became the aspirational standard for audiences. Through the power of television, viewers in the ’50s were told that happiness (for a white man) meant being married to a dutiful housewife, having obedient children, and living in a spacious suburban home. Of course, this message was largely classed, gendered, and raced: people of color and queer people were invisible, and heterosexual women had assigned roles.

Based in part on the hit radio show, My Favorite Husband that Ball starred in when CBS was interested in spinning the show to television, the studio was hoping to have its star paired with her fictional husband, Richard Denning. Ball, however, thought the show would be an excellent vehicle for her and Arnaz. Though executives were nervous over featuring an interracial marriage, Ball and Arnaz took their dual act on the road and were a hit in that format.

Convinced that audiences would shut their sets off at the non-mainstream site of Arnaz and Ball canoodling, a pilot was ordered. Both Ball and (especially) Arnaz proved to be savvy, insisting on ownership of the show, and the latter would go on to innovate sitcom production, working with cinematographer Karl Freud, to use three cameras to film the show. This way of filming also allowed for a live studio audience, which worked better with Ball’s style of comedy.

I Love Lucy is indeed a pioneering show, but in terms of gender politics, it doesn’t challenge too much. Lucy Ricardo (Lucille Ball) is a housewife who is expected to keep a home for her working husband, Ricky (Desi Arnaz). Although the show’s stars repeatedly insisted that I Love Lucy didn’t intend to take on world-changing progressive issues, it was far more subversive than they let on.

Though Lucy is a housewife, she isn’t content with staying at home, keeping house, and being a mother to Little Ricky (Keith Thibodeaux). Instead, Lucy is envious of her husband who has a successful career in show business as a bandleader and singer. Much of the comedy from I Love Lucy comes from Lucy’s unending quest to break out of her household duties. She eyes entertainment as the way out. Every time Ricky admonishes Lucy with a “You can’t be in the show,” he is thwarting her ambitions of escaping placid domesticity.

The other notable aspect of I Love Lucy that is rarely commented on is the matter of what makes a family. On I Love Lucy, the idea of family is somewhat queered with the inclusion of neighbors and landlords, Fred and Ethel Mertz (William Frawley and Vivian Vance). The Mertzes aren’t just friends of the Ricardos, they are family. Whenever Ricky and Lucy need help or advice, they turned to Fred and Ethel. The Mertzes help raise Little Ricky, acting as a second set of surrogate parents.

Throughout the show’s run, we encounter the Ricardos’ extended biological family. Lucy’s mother (Desiree Evelyn Hunt), in particular, serves as a recurring character on the program. The most dominant family structure on I Love Lucy, however, isn’t the Eisenhower-era model of a nuclear family (mom, dad, kid), but a very urban adaptation of a family: close friends who share in each other’s lives.

The alternative family is a television trope that works to use an ensemble cast in plots that exist outside of traditional domesticity. Stories of alternative families in American sitcoms are set in large cities, particularly if the sitcoms are set in the workplace. Often the protagonist is a singleton, a transplant to the city without deep ties. The alternative family – sometimes coworkers or wacky neighbors – is there to supplement or replace the lead character’s biological family. The alternative family is a decidedly “queer” concept, a way to mirror how queer people migrate to large cities and create families of friends or coworkers to provide loving communities.

So with I Love Lucy, we see the concept of the nuclear family grafted onto the alternative family. Though Ricky and Lucy are married with a kid, just like they are supposed to be according to presumed cultural norms, Fred and Ethel are on hand to help raise Little Ricky. But Fred and Ethel aren’t there just to be co-parents, they also act as accomplices to Lucy’s schemes, participating conspirators in her plots against Ricky’s presumed authority. Though the Mertzes are clear-eyed about Lucy’s absurdities (often refusing in vain to join in on the hijinks but inevitable folding), their love for her and their desire for her happiness means they would often don silly outfits, place themselves in physical danger, or cover themselves in messy slop to help her out.

Though Desi Arnaz’s assessment of the show’s success is very generous (and accurate), it has to be said that the cast is made up of possibly the greatest comedic ensembles in television history. Much time is spent on evaluating the peerless comedy genius of Lucille Ball. She’s clearly a supremely gifted comedienne, able to make even the most ridiculous situation seem believable. Through her commitment to the situation at hand, Ball convinced her audience that every square inch of her scenes is realistic. A hardworking and dedicated pro, the comedienne worked exhaustively (no small feat, given that she suffered from rheumatoid arthritis) to ensure that the outcome on screen was just right. Even if she was an extravagant clown, Ball’s comedy was rooted in realism. Just watch the progressive way she slides into intoxication in the Vitameatavegamin sketch.

But a great comic needs a great straight man, and she had three, especially Vivian Vance. A consummate comedienne in her own right, Vance was a brilliant partner who worked to heighten both the comedy in the scenes but also the verisimilitude. Behind the scenes, the two actresses reportedly had a complicated, oft-flinty, relationship, but onscreen, they were genuinely in love with each other. Though Lucy and Ethel sometimes fall out (some of the best bits in the show focused on conflict) the two always kiss and make up. Ball and Vance’s friendship was paramount to the show’s artistic success.

With William Frawley’s Fred Mertz, Lucy has an almost paternal relationship, given his age and curmudgeonly demeanor. Written as an oft-petty skinflint, he, like his wife, also gets roped into Lucy’s antics, although he’s always trying to pump the breaks on the capers. Whether it’s donning drag, lugging John Wayne’s cement footprints, or braving the choppy waters on the Staten Island Ferry, Fred unwittingly joins in Lucy’s hare-brained schemes, putting aside his very reasonable objections because he cares.

Some of the best moments of the show aren’t necessarily the ones that have been entered into the canon of television history. Of course, Lucy working at the candy factory, Lucy doing a TV commercial, Lucy stomping grapes are all moments that are just as fresh and funny today as they were over half a century ago. These iconic moments of comedy are rightfully lauded and revered because they showcase the brilliant talent of an ingenious artist.

But there are other key moments in the show’s history that provide the episodes with the warmth and joy that make I Love Lucy more than just a vehicle for Ball’s death-defying stunts. Below are some episodes that shift away from the more raucous moments of the show’s lore and zero in on the relationships between Lucy and her friends. It’s in these moments that we understand why audiences responded so well to the show. It wasn’t just the slapstick comedy as inventive as it was – but it was the humanity in the show. Though the show’s title is I Love Lucy, it isn’t just about Ricky’s romantic love for Lucy (though there are plenty of great moments of romance on the show) but the love also applies to Fred and Ethel, who love the titular redhead, too.

Indeed, one of the most enjoyable moments of any I Love Lucy episode is when the resolution is met, the characters all start to laugh, the loud end theme blares over their laughter, and we’re left with the image of the smiling, laughing faces fading into black: the last image we have of them before the episode ends. It’s also the lasting image we have of them. The four seemingly disparate goofballs, sharing a laugh for television eternity.

Below are ten episodes from the original six-season run of the show (not counting the hour-long The Lucy-Desi Comedy Hour episodes which, despite isolated moments of brilliance, aren’t nearly as enjoyable as the main series), in which the friendship between the characters is an important theme in the plots. With the exception of “Lucy Visits Grauman’s” and “Lucy Goes to the Hospital”, these episodes are not included in the pantheon of great television comedies. Though physical comedy is an important part of every episode of I Love Lucy – the writers stuck to a pretty solid template: introduce the plot, bring in the conflict, give the audience the physical comedy centerpiece, and then the resolution. What is notable about these episodes is that the genuine affection these characters have for each other shines through.