The Gilded Cage of Melodrama: When Yellowstone Swallowed the Soap

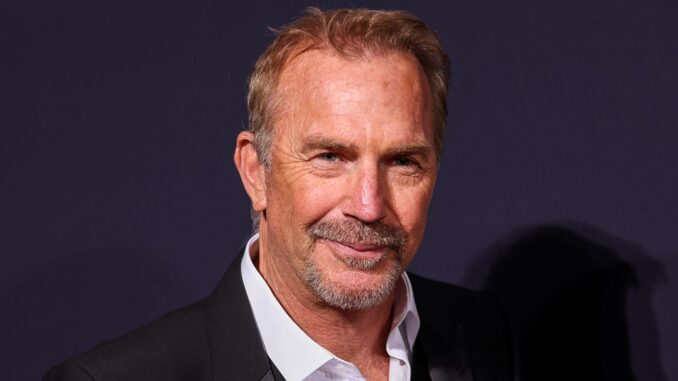

The sprawling, sun-drenched vistas of the Dutton Ranch once promised a saga as vast and untamed as the Montana wilderness itself. Yellowstone, in its nascent seasons, captured the zeitgeist with its potent blend of rugged Western allure, cutthroat power struggles, and the magnetic pull of a family fighting for their land and legacy. It was a show that felt cinematic, almost operatic, in its scope and ambition. Then, a seismic tremor hit, not from a geological fault line, but from the words of its stoic patriarch, Kevin Costner, who famously – and damningly – labeled the show’s later direction a “soap opera.” His indictment wasn’t merely the grumbling of a departing star; it was a mirror held up to a narrative descent, illustrating the perilous tightrope walk between compelling drama and manufactured melodrama, and how easily a show can tumble into the latter.

To understand the sting of Costner’s critique, one must first recall Yellowstone‘s initial grandeur. It wasn’t just a show; it was an experience. The landscapes were characters in themselves, vast and indifferent to human squabbles, yet deeply intertwined with them. John Dutton, portrayed with grizzled gravitas by Costner, was a modern-day king, presiding over a feudal empire with a quiet ferocity. His children – Kayce, Jamie, Beth, and Rip – were archetypes of loyalty, resentment, ambition, and unwavering devotion, each a complex cog in the Dutton machine. The early conflicts were visceral: land developers, tribal politics, the relentless push of modernity against tradition. The stakes felt real, the violence earned, and the emotional beats resonated with a raw authenticity that distinguished it from its network counterparts. This was a narrative built on the bedrock of genuine conflict, not merely the shifting sands of manufactured drama.

The “soap opera” designation, however, is a potent one, conjuring images of contrivance, repetition, and a relentless focus on interpersonal drama at the expense of thematic depth. And, slowly but surely, Yellowstone began to embody these very traits. Characters who once possessed clear moral compasses found themselves drifting into increasingly erratic and unbelievable behaviors. Plot lines grew convoluted, relying on improbable schemes, sudden revelations of long-lost secrets, and miraculous survivals that strained credulity. Deaths became less about impact and more about shock value, while resurrections (or near-resurrections) blunted the consequences of danger. Every triumph was short-lived, every victory immediately undermined by a fresh, often ill-defined, antagonist. The biting dialogue that once cut to the bone began to feel performative, a series of grand pronouncements designed to elicit gasps rather than illuminate character.

Consider the endless cycles of betrayal and reconciliation among the Dutton siblings. Jamie’s Hamlet-esque vacillation between loyalty and resentment became a narrative quicksand, dragging down potentially compelling character arcs into predictable patterns. Beth, a force of nature in her own right, often found her intelligence and ruthlessness channeled into elaborate, cartoonish vengeance plots that felt more like a Saturday morning cartoon than a gritty Western drama. Even the central conflict over the land, once the show’s beating heart, started to feel like a backdrop for an increasingly tangled web of personal vendettas and romantic entanglements that superseded its original, weightier themes. The plot no longer seemed to evolve organically but rather to spin its wheels, creating new crises simply to fill episode counts, relying on cliffhangers that felt less like earned suspense and more like narrative blackmail.

Costner’s lament, then, isn’t merely about scheduling conflicts or a star’s ego; it’s a profound artistic statement. As the linchpin of the series, embodying the stoicism and moral ambiguity that defined its early success, he was arguably the closest conduit to its original vision. To see the show devolve into a predictable cycle of melodramatic twists, where character integrity is sacrificed for shock and genuine stakes are replaced by sensationalism, must have felt like a betrayal of the very narrative he helped build. His “soap opera” label illuminates the point where a story stops being about the slow, arduous process of life and death on a ranch, and starts being about keeping a perpetual dramatic engine running, no matter how much fuel of absurdity it consumes.

In the end, Yellowstone‘s journey from a prestige drama to what Costner perceives as a “soap opera” is an illustrative tale of the perils of success in long-form television. The pressure to sustain high ratings, the temptation to escalate drama beyond believability, and the commercial demands of a sprawling narrative can slowly erode a show’s artistic foundations. Costner’s final, pointed words serve as a stark reminder: even in the vast, untamed wilderness of storytelling, there’s a crucial difference between a genuine struggle for survival and a meticulously choreographed spectacle of manufactured angst, a difference that defines the very soul of a series. The Dutton Ranch, for all its sweeping grandeur, ultimately became a gilded cage, trapping its characters, and perhaps its audience, in an endless, looping melodrama.